50 years ago, many psychiatric hospitals closed. Did that cause today's mental health crisis?

F

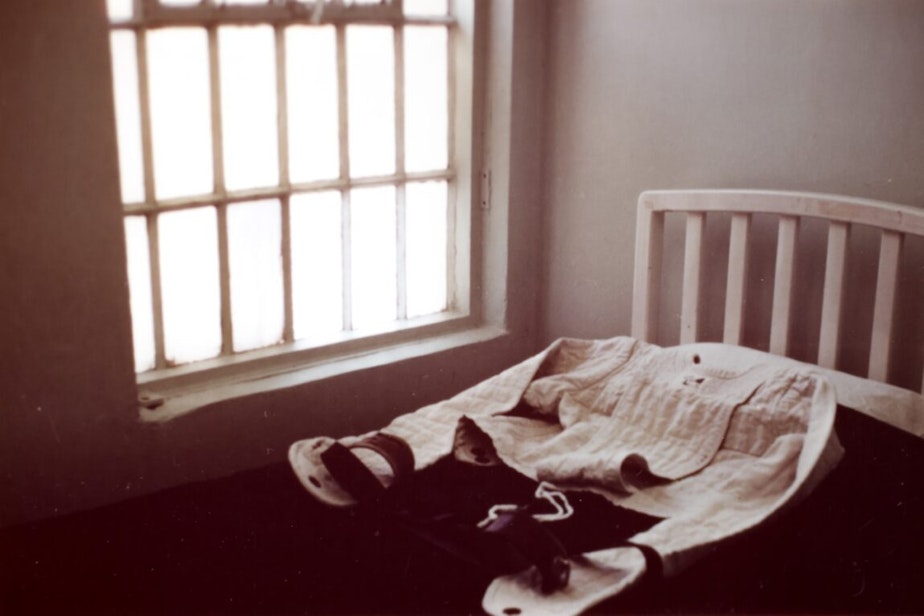

ifty years ago, psychiatric hospitals across the U.S. were closed, including one of the three in Washington state. The idea behind “deinstitutionalization” was to replace facilities like Northern State Hospital in Sedro Woolley, Washington, with community health care that reintegrated mentally ill people into society instead of locking them up.

People often blame this national movement for the mental health problems they see today on city streets, including in Seattle. Ask almost anyone about chronic homelessness and they will inevitably point to the decision in the 1970s to close asylums and release patients, often with little resources and no psychiatric care.

“Like all myths, there’s an element of truth here,” said Will James, host of the KUOW/Seattle Times podcast “Lost Patients.” “But what’s more interesting are the ways in which this story we’ve been telling for decades is wrong.”

On this week’s episode, James and Seattle Times’ reporter Sydney Brownstone explore the myth of deinstitutionalization and the complicated process that cut funding to state hospitals without fully investing in alternate care for people suffering from mental illness.

Sponsored

Joanne McInnes, who worked as a psychiatric nurse at Northern State, said the hospital had moved away from some of its more questionable practices, like lobotomies, that gave it such a bad reputation before it closed in the early 1970s.

“We wanted it to be different,” McInnes said. “We wanted to be proud of what we were doing.”

The shift to an open-door policy, helping to heal people as opposed to hiding a social problem, led to lower patient populations at state psychiatric hospitals. This changing attitude and approach to treatment was aided by the introduction of psychotropic drugs to treat mental illness, which allowed patients to return to society.

While this was seen as a good thing by psychiatrists, it also led state government to question continued spending at the hospitals, when the numbers of patients living there had dropped so precipitously.

But many of the more seriously mentally ill were not served by the community care that ended up being funded in Washington state and elsewhere.

Sponsored

“I felt like the patients weren’t taken care of,” said McInnes, who was transferred to Western State Hospital after Northern State was shut down. “There wasn’t the follow up and the support systems knocked out.”

The “Lost Patients” team tracked down former Washington Gov. Dan Evans, who was a rising star in national politics when Northern State closed.

At the time, Evans said that the all the state’s counties had “viable community mental health programs in operation,” but he also said the state would need a substantial increase in funding to “serve all those who need help.”

Gov. Evans, who is now 97 years old, said the move to close psychiatric hospitals was done with good intentions, and he pointed out that the change was part of a national trend.

He said the approach to mental health has changed dramatically over time, in part because people aren’t just being locked away. But he admitted that the move had mixed consequences.

Sponsored

“It was a time of change, but during a time of change like that you start down a different path or different, multiple paths seeking better answers,” Evans said. “Sometimes you find them, sometimes you don't.”

To listen to the full episode of “Lost Patients,” tap the link above.

Looking for mental health resources? KUOW compiled an "Acute mental health resource guide" that can help.