'Thousands of stitches, all by hand': a look at Puget Sound's artisan sailmakers

The pleasure craft of today are very different from the tall ships that were once the only connection to other continents.

Some of those old-style ships are still around, and they need regular maintenance on their large, billowing sails. But there aren’t many businesses that make these kinds of sails anymore.

One of the last places in the world that still does is right here in the Puget Sound region.

N

ahja Chimenti feeds two stacked panels into a sewing machine. Her father, Wayne Chimenti, fits the corner of a sail over his knee to begin banging in a brass ring, while her mother, Nicole Chimenti, watches on from a nearby sill.

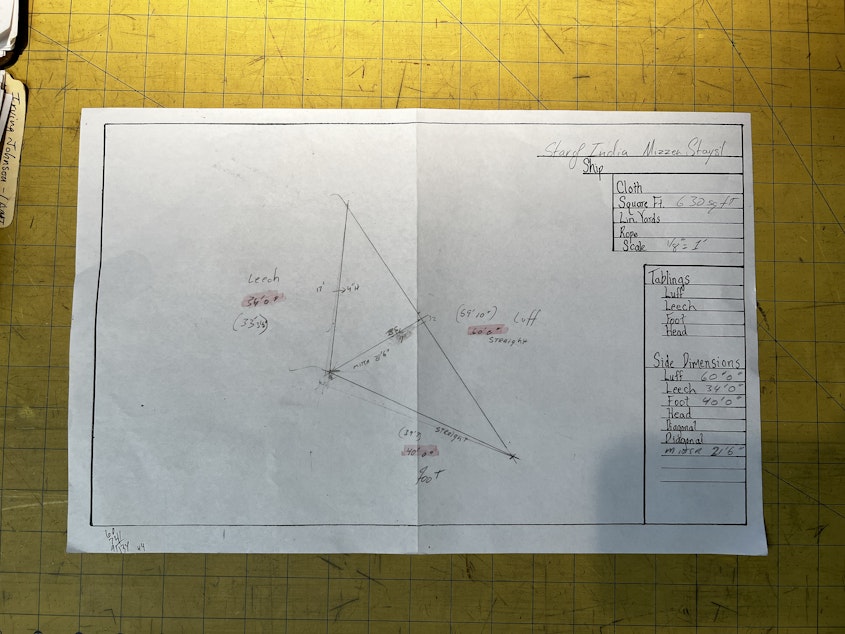

The family business, Force 10 Sailmaking and Rigging, specializes in hand made sails for tall ships, also known as schooners and square riggers. These vessels were used for oceanic travel throughout the 1700s to today, and the Chimentis are currently working on a sail for a museum ship called the Star of India, a 250 foot vessel built in 1863 that now resides in San Diego.

The process of making a sail from scratch starts in a gymnasium. The sail makers chalk in the dimensions of the sail on the floor, then roll out the cloth and tick things off. That cloth then makes its way back to their relatively small sail loft, a workshop sitting on the second floor of a building on Marrowstone Island.

That cloth is carefully sewn together by Nahja.

"It's 300 pounds of cloth alone," she says. "And then we're adding all of the rope and all the hardware to that as well."

Sponsored

On some sails, the seams can be 40 to 50 feet long, all in one neat, straight line. Each seam gets three rows of stitching to it, with up to 20 seams per sail.

"I've definitely spent days sitting at the sewing machine calculating in my head how many miles of stitching I happen to be doing at that time," Nahja says.

The business started when Wayne began studying marine biology in Mystic, Conn. Once he stepped on a boat, it was difficult to go back on land. He worked his way up to captain, sailing throughout the Pacific, where he met his future wife, Nicole. But sailmaking wasn't always his passion.

Sponsored

"I was always drawn to rigging," Wayne says, referencing the job of tying various knots and splices to engineer the ship. "Riggers are very keen to show you everything. Sailmakers are absolutely the opposite."

That changed when he met renowned sailmaker George McNeil in Sydney, Australia. McNeil was a generational craftsman, and agreed to teach Nicole and Wayne the ways of sailmaking.

"We'd go into six o'clock at night and George would sit us down and say, 'Okay, this is what you need to do tonight. You need to sew these together. Here's how this goes together.'"

The Chimentis began making sails, and then they made a family. Nahja spent her early life on the ocean, climbing masts and becoming the second of her generation to pick up the craft. The family visited Puget Sound to help build a ship and were smitten by the July weather. They decided to stay, and the land-based Force 10 Sailmaking and Rigging loft was born.

Sponsored

Nahja now heads the business, doing seam work to the final stages of the sailmaking process. Wrangling cloth up to 13 layers deep, she hammers an awl with a mallet to make a constellation of holes. These will be used to attach a rope around the edge of the sail, like a kind of fringe. But that rope can't be done with a sewing machine, so the holes and the thread will need to be fashioned manually.

"Thousands and thousands of stitches, all by hand," Wayne says.

Sponsored

The braiding of that thread is intricate, and Nahja comments that each sailmaker has their own signature braid in each corner of a sail. Although, onlookers won't be able to see these braids — to protect the stitching from chafe and the sunlight, it will be covered with a piece of leather.

"Some people make engines, and we make something much simpler that, in a lot of ways, does the same thing," Nahja says. "It powers an entire ship. It's kind of like building a wing for a bird."

With dedicated work, a sail can be finished in about two weeks time. The sails are then sent to their intended ships. It can last up to 20 years with proper care.

But the craft of this kind of traditional sailmaking is also fragile. Wayne says that small sail lofts are constantly closing as technology and corporatization makes mechanical sailmaking easier than ever. But what goes missing in those sails is longevity, the personal knowledge of how a sail will be pushed and pulled, and the assurance that sails are made to the same specifications they were designed with 100, 200, and 300 years ago.

Sponsored

Nahja is continuing the Chimenti practice, but they also take on apprentices. Wayne remembers the difficulty of finding quality sailmaking instruction in books and literature when he first started his craft.

"There's so much to be taught," he says. "Not only the business side of it, but the craftsmanship so that you keep this lineage going, so that it just doesn't disappear altogether."

"There's so much to be lost," Nahja adds.