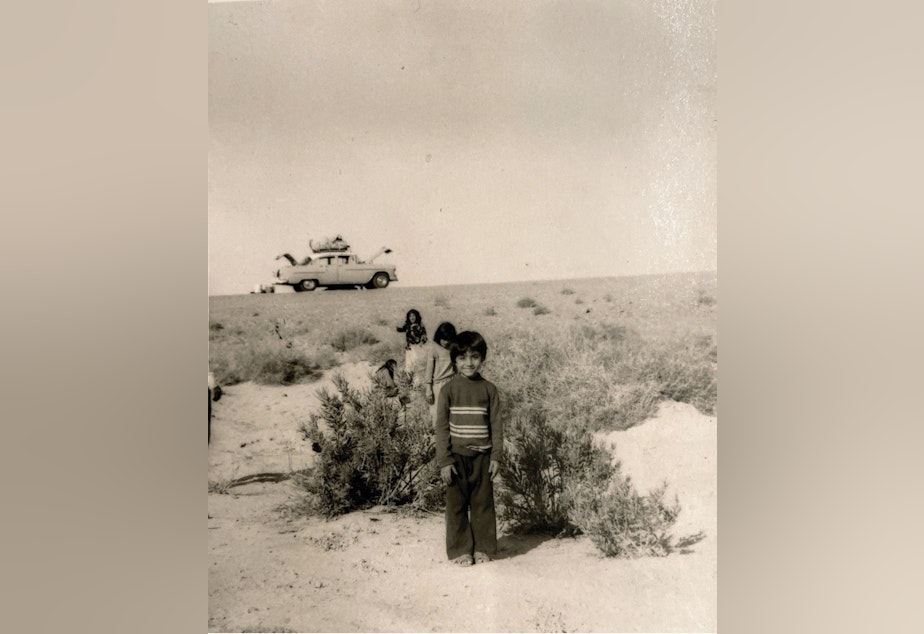

She escaped Iran at age 15. This is her story

As told to Bill Radke, host of The Record on KUOW. Mahvash Khajavi-Harvey is the author of Daylight Forever.

When I was six years old, the Islamic revolution of 1979 took shape in Iran. And with that, it brought a lot of changes.

Women lost a lot of rights. Shortly after that, they focused on the religious minority, which is called Baháʼí faith, the religion of my family. The Baháʼí were persecuted. Hundreds of Baháʼí were killed; they were sentenced to death, just for their belief.

Everyone who was employed by the government was fired, including my father. And everyone lost their retirement. They seized bank accounts. They took everyone's property. Baháʼí children could not attend universities, couldn't legally get married, couldn't legally leave the country.

When I was almost eight years old, my family was threatened in a neighborhood they had lived in for over 20 years. They were writing graffiti on our walls, they were asking us to leave the neighborhood.

One night, the local religious clergy [said] that they could burn our house. One of the neighbors told them over his dead body they could do that. The neighbor ran to our house and warned my father. He said, 'I'm going to stand guard at your door. And you need to pack up and go.' So we had to pack up and leave immediately.

Sponsored

My father, in that moment, realized why our walls were always wet in the morning, when he got up to go to the bakery to get bread. This neighbor had been cleaning the graffiti without my father even knowing it.

We moved across the Tehran, living near Tehran's International Airport. At this time, the war started between Iran and Iraq, it was the eight-year long war. The airport was the main target. We were targeted a lot.

When you experience that trauma and that fear, it never leaves you. It's something that changes you permanently. I have done years and years of therapy, and I have tried many different techniques. And something just triggers it. Even the Seafair planes.

We were in Oahu (Hawaii) a few years ago, and we were in the theater watching a documentary from World War II. When the sirens went off, and they started dropping bombs, I couldn't stop crying, and I had to leave the theater. It is such an emotionally traumatic experience that no one should ever experience, especially not children. And that was the first decade of my life.

When I was 14 years old, a freshman in high school, I realized that my sister, who was four years older than me, a senior, could not attend university. I was a straight-A student. We had put all our focus and energy into school, and trying to distract ourselves with just digging into the books and learning. I realized, as a Baháʼí woman, there was no future for me in Iran.

Sponsored

If I survived the persecution, if I survived the bombing, I still couldn't go to university. I couldn't become an independent woman who I was raised to be, who my father had told me I would be one day. And that's when I started realizing that staying in Iran was not the choice. It was just the surrender to fear, to darkness, to bombs, to no opportunity.

For about six years, every night, when it got dark in Tehran, they would cut the electricity across there. Because a lot of the residential neighborhoods were getting bombed. Everyone was instructed – we taped all the windows in our house, and everybody hung thick blankets to keep the shards of glass away. They would cut power, and we would sit around doing homework, having dinner by candlelight. It was spooky, it was dark, it was quiet, nobody was out, and the sirens would go off.

You stop breathing. The ground shakes, and your body goes numb. You want to scream, but nothing comes out. You put your shoes on, you put your jacket on. You go into this closet, and you wait. You're in a state where you can't think, you can't breathe, the fear takes over. And it's such a horrible experience.

I would be lying down, waiting for the bombs. And tears would come down on my face, and I would wish that I had a spaceship to escape all of this. And then I would come back in the morning to go back to school. That’s why the book is called Daylight Forever.

For decades, it was easier for me to put it away, not think about it, not talk about it. It was in a closet locked up. And I was focusing again on school, on my new life and my opportunities that I was given in this country.

Sponsored

But in the last few years, the changes across the world have proven to me that I can't be silent. I want to speak up. I want to speak for those children in Syria who are getting bombed. For all the children who are in danger anywhere in the world. It is not fair. It is not their choice. They are victims and they are lifetime victims of violence, whether it's war, whether it's persecution, whether it is gang activity.

Where you get born or raised, it's not a choice. It's a chance.

When my daughter was 12 years old at school here in Seattle, a boy announced to classmates that there were too many immigrants and refugees in this country. This was about a month after the election of 2016.

My daughter asked the boy, ‘Do you know their stories? Do you know their struggles?’ And the boy said no. She said, ‘Well, my mother is a refugee, my aunt, my uncles, my family. A lot of our family, friends are. And if you know their stories, you would not say such things.’ The boy, unfortunately, said to her, ‘Well, is your mother documented? Or is she going to get deported?’

When I picked her up that day from the school bus, she was crying, she was very upset.

Sponsored

As I held her in my arms, she asked if I would write a book and share my story. And I said yes; I wanted to calm her down. She felt like I was disrespected. She felt like she knew my story. She knew how hard I had worked. Later, I said to her, my story is not unique. There are millions of people who have similar stories. She insisted. ‘If you can share your struggles, it might help.’

When I was 15 years old, with a backpack on my back with a set of pajamas, toothbrush and toothpaste, some medicine, feminine hygiene products, socks, a few pictures, a phone book, I walked away from my home.

I had begged for that. I had asked my parents, I had pressured them, to send me away out of the country. And when the time came, they sat me down, and said, 'We have found a way to get you out of the country.' I was confused because I thought we would all leave together. They were like, 'No, we cannot afford to leave at this point. You are leaving.' I was scared. But I was afraid that if I show that, they might change their mind.

Mahvash Khajavi-Harvey is a dentist in Seattle and the author of Daylight Forever. This transcript has been edited for clarity and length.