Boeing CEO Faces Tough Questions On 737 Max Plane's Design

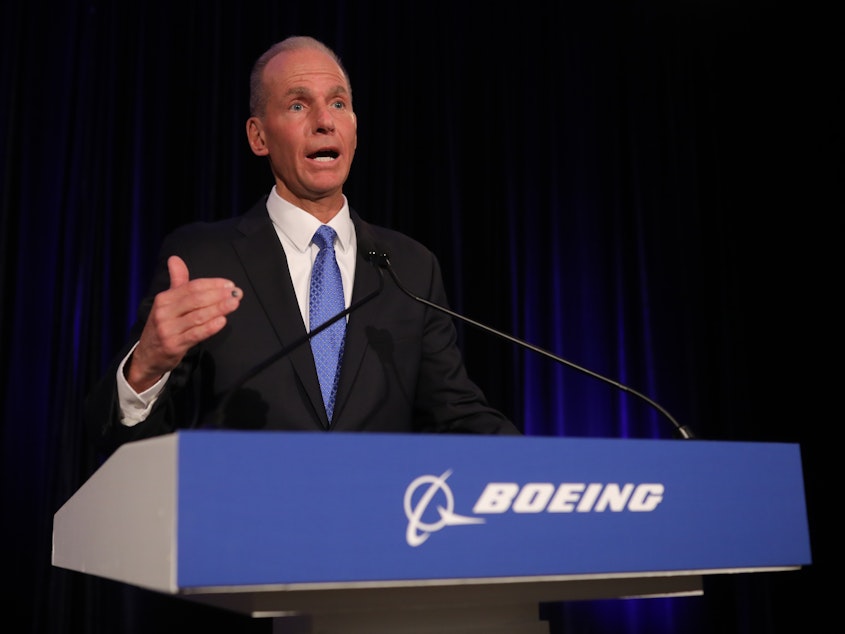

Six months to the day after the first of two deadly crashes of its 737 Max jets, Boeing's chief executive faced hard questions from both shareholders and reporters about the plane's safety on Monday.

But through it all, CEO Dennis Muilenburg stuck to the script, using the same phrases the aerospace company has used repeatedly since the crashes: That the company "owns" the responsibility to update its software, but does not precisely "own" the disasters. The crashes have been linked to erroneous sensor readings, but the company says that's only "one link in a longer chain of events," and not proof of a design flaw or a broken process.

Muilenburg spoke at a brief and testy press conference that followed a shareholder meeting in which there was a call to split the roles of Boeing's CEO and chairman of the board — positions Muilenburg currently holds. That proposal was rejected.

Boeing is under particular scrutiny for the 737 Max's software system known as MCAS — the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System. The company says the software is designed to enhance the pitch stability of the plane when it's at an elevated angle of attack, so that it feels to pilots more like other 737s.

"Pilots can override MCAS," NPR's Daniella Cheslow reported earlier this month. "But a lot of pilots say they didn't know the software existed until after the Lion Air crash. They say the manual did not explain it or provide explicit instructions on how to disable it."

Sponsored

Capt. Jason Goldberg, who flies for American Airlines and is a spokesman for its union, told NPR that while it's true pilots train to overcome problems with a plane's pitch adjustment systems, a malfunctioning MCAS system creates other distracting problems.

"You would have the stick shaker, which [activates] a rather violent aggressive shaking of the control column," Goldberg told Cheslow. "You would have the appearance of unreliable airspeed. You would have a number of warnings that don't immediately or intuitively give the impression of a pitch trim problem."

At Monday's news conference in Chicago, Muilenburg defended the MCAS system.

"We want the airplane to behave in the air similar to the previous generation of 737s — that's a preferred pilot feel for the airplane, how it feels as they're flying it, and MCAS is designed to provide those kind of handling qualities at high angle of attack. So it's a purposeful design," he said. Muilenburg added that it wasn't something that required separate training.

"When we train on the airplane, you're being trained on MCAS," he said. "It's not a separate system to be trained on."

Sponsored

Muilenburg reiterated the changes that Boeing has said it will make to the Max's systems. One change is that the MCAS system will rely on data from two sensors, instead of just one, to determine whether the plane is in danger of aerodynamic stall. Also, if MCAS is activated, the system will act only once instead of repeatedly forcing the nose of the plane down.

The Boeing CEO stopped short of saying there was a mistake in the process that certified MCAS for use on the airliners, saying the same processes have worked for decades.

"There is a chain of events," Muilenburg said, when a reporter asked him whether Boeing was overly confident in pilots' abilities when they didn't know MCAS was there in the first place.

"There are multiple contributing factors. There are factors that we can control in the design and in this case that common link related to the MCAS system and its activation," he said. "We're going to break that link and this will prevent accidents like this from happening again."

Meanwhile, the 737 Max planes remain grounded. Muilenberg says Boeing's focus is on getting them flying again, safely. He also says the company will "do everything possible" to regain the public's trust. [Copyright 2019 NPR]