Buying hot dogs was an act of resilience for my grandfather in the Jim Crow South

From 1877 through the 1960s, Black Americans were still not entirely free. Slavery was abolished, but Jim Crow laws were put in place by white leaders to uphold that same violent oppression of Black bodies.

RadioActive’s Nyla Moxley shares the story of one summer her grandfather spent in the Jim Crow South.

This story discusses racist violence.

[RadioActive Youth Media is KUOW’s radio journalism and audio storytelling program for young people. This story was entirely youth-produced, from the writing to the audio editing.]

M

y grandfather, George Moxley, was born in Lancaster, Ohio, in 1941. He was raised 35 minutes away, in Columbus.

There, his public school was integrated, but not prejudice-free. My grandfather remembers Black and white children playing on separate playgrounds until he reached junior high.

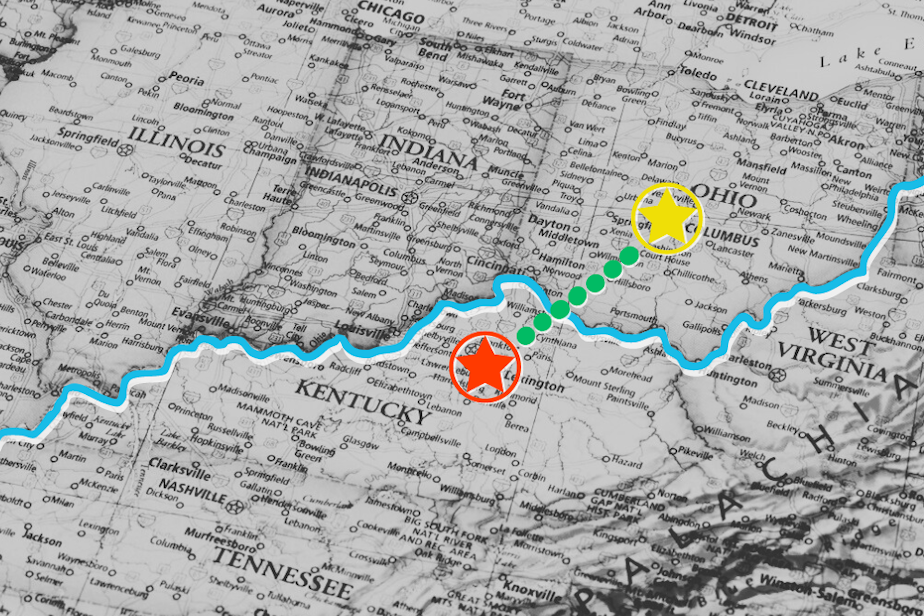

In 1954, when my grandfather was 12 years old, he and his father drove across the Ohio River to Kentucky to spend the summer working in Lexington.

Sponsored

In Kentucky, my grandfather said, the racism he encountered was much stronger, and much more dangerous, than it was in Ohio.

"Just 150 miles made a difference," he said. "When you cross the Ohio River — Jim Crow. You had to go to the back of the restaurant. You had Black and white fountains. Everything changes for Black folks."

That summer, my grandfather and his father worked tending to horses at the Lexington fairgrounds. They were responsible for taking care of two horses that belonged to a white family.

Sponsored

One day, my grandfather and his stable mate decided to buy hot dogs off a white girl who was selling them.

In the end, he’d eaten a whopping total of nine hotdogs.

"The guy that bought me the hot dogs said, 'Man, you done ate so many hot dogs, we gon' call you 'Hot Dog' from now on,'" my grandpa remembered.

And that's how my grandfather got his nickname: George "Hot Dog" Moxley.

At first, this story seems funny and innocent. But there’s one detail that changes things.

Sponsored

There was a group of white boys spying on the transaction.

"There was three little guys that was peeping around the corner, seeing who I was," my grandfather said.

My grandfather concluded the white boys felt like their superiority was being threatened — like they were appalled he would even speak to a white girl.

"When they're envious, it’s a fine line, hate and envy," my grandfather said.

After he finished his job that day, my grandfather went to watch the horses being sold. While he was standing there, someone tapped him on the shoulder. It was the same boys from earlier.

Sponsored

"And I turned around and this boy hit me upside my head with a rock in his hand, knocked me almost out," he remembered. “I’ve been hit before, but that was a sucker punch.”

His father — my great-grandfather — witnessed the attack, and jumped in without hesitation. He wasn’t trying to save my grandfather from the fight, but from the bigger implications — like triggering an angry white mob.

Later on in the day, my grandfather saw one of the boys from the pack standing on his own.

"And I chased him down and ran him off. And he took off running," he remembered.

After that altercation, my grandfather went back to the stable to stay the night.

Sponsored

"Then behold, here comes my dad," my grandfather said.

"'God dangit boy, you're down here messing with these people,'" he recalled my great-grandfather saying. "'You know you ain't supposed to be doing that! And the guy told me they got 30 people looking for you to do harm!'"

My great-grandfather took my grandfather off the fairgrounds. They were gone in just 24 hours, back across the river to Ohio.

"It's kind of discouraging, because I didn't do nothing wrong, but I got charged twice," my grandfather said.

As he retold me this story for probably the fifth time, my grandfather and I discussed how envy, paired with a system that promotes violence, is deadly.

"It was bad in the 50s," he said. "Emmett Till, and a lot of them guys, went down there and just spoke to someone."

In 1955, only a year later, Emmett Till was found brutally murdered on the shores of the Tallahatchie River in Mississippi.

Till was lynched by a group of white men after a white woman said he whistled at her.

Till was just 14 years old when he was lynched. He and my Papa were born in the same year.

As I reflect on my grandfather's legacy, I realize there’s something profound in his bravery.

Here was this little Black boy who was audacious enough to stand up — not just to a pack of white boys — but to an entire system.

I have often struggled with the feeling of social inadequacy because of my radical Blackness.

The reality is, my Papa could have been killed simply because of his skin color. Despite that, he has always been authentically himself. He teaches me to be just as proud.

"I'm just glad to make it through that, and them 30 people didn't get a hold of me," he said. "I'm still here. What do you think about that there, Nyla?"

That is why I am telling his story. And he is why I am here, and able to do it.

This story was produced in a RadioActive Youth Media introductory workshop for high school-age youth. Production assistance by Troy Landrum Jr. with support from Stefan Ney. Edited by Kamna Shastri with support from Deborah Wang. Prepared for the web and broadcast by Kelsey Kupferer. Music is "Tide" by Marta Cascales Alimbau.

Find RadioActive on Instagram, TikTok, YouTube and Facebook, and on the "RadioActive" podcast.

Support for KUOW's RadioActive comes from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Discovery Center and BECU.