Something's killing coho salmon in Seattle. Car tires a prime suspect

When autumn rains return to western Washington, so do coho salmon. But in many of the creeks they swim up, something in the water leaves fishes gasping for air. They die quickly, before they manage to spawn.

A new study points at chemicals from tiny bits of car tires as a prime suspect in the fishes’ untimely deaths.

Most cohos that come to Miller Creek, in the leafy Seattle suburb of Normandy Park, die prematurely.

On a sunny September morning, researcher Ed Kolodziej from the University of Washington spotted a dozen young cohos, each about two inches long, darting in and out of the shadows on Miller Creek. Their two-foot-long elders were likely just offshore, waiting for rains to raise the creek and creeks like it all around Puget Sound.

Virtually every coastal stream in Washington where water flows year-round is home to coho salmon.

But those rains also help send a toxic stew into urban and suburban creeks around the sound.

“Stormwater flows actually kill these coho salmon before they have a chance to reproduce,” Kolodziej said.

Heavy rains carry a chemical cocktail of motor oil, wiper fluid, brake dust and other gunk from roads and driveways into nearby drains, creeks and eventually Puget Sound.

Stormwater runoff from highways and roads is the largest source of toxic chemicals in the sound, according to the Puget Sound Partnership.

Scientists have long known that road runoff kills cohos, but they still do not know which of the thousands of chemicals in it are the lethal ones for suburban salmon.

To narrow down the lineup of suspects, salmon researchers enlisted volunteer creek watchers. In creeks in Seattle and Normandy Park, they went on the lookout for coho acting weird, swimming aimlessly and gasping for breath: signs they were about to die an unnatural death.

Lab tests showed the runoff that was killing cohos consistently had some unexpected ingredients.

“We were surprised to see a really strong signal of chemicals coming out of car tires, actually,” Kolodziej said.

Their findings appear in the journal Environmental Science and Technology.

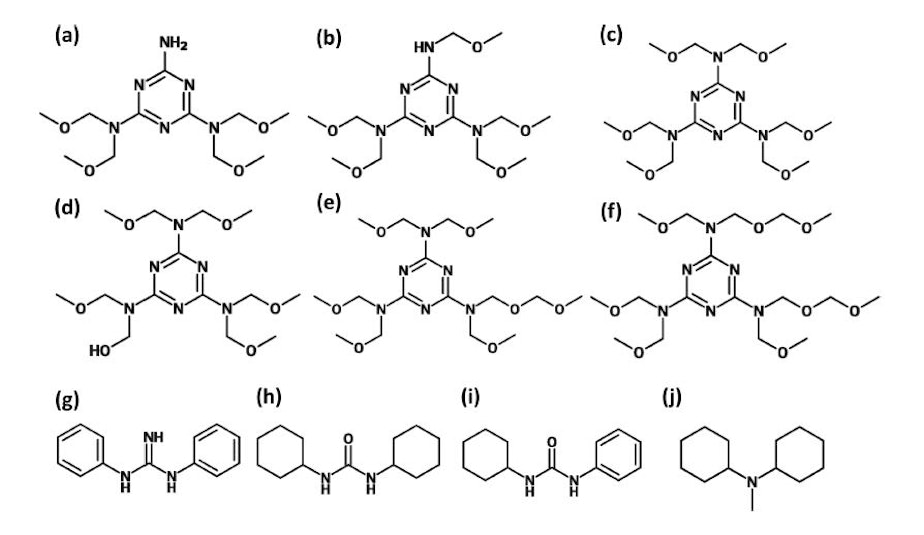

Researchers found chemicals used in tire manufacturing, including diphenylguanidine and the nearly unpronounceable hexa(methoxymethyl)melamine, or HMMM.

“It's a real mouthful, but quite common actually in some of our urban creeks,” Kolodziej said.

Even so, the new study says it is the first to report finding HMMM in a North American waterway.

Miller Creek in Normandy Park, Washington. KUOW / John Ryan.

Sheens of motor oil or antifreeze can be seen on many roadways and parking spaces. But driving also leaves little smears of tire behind.

“As our tires wear out, we're leaving bits of that tire rubber behind on our roadways,” Kolodziej said, “and chemicals are actually leaching out of that tire rubber and polluting our stormwater and subsequently polluting our urban creeks.”

Paper coauthor Jenifer McIntyre, an ecotoxicologist at Washington State University in Puyallup, is now testing different components of worn tires to try to zero in on what is killing these suburban salmon.

"These chemicals are out there. They're there in our creeks," Kolodziej said. "We should understand them better."

Little is known about the toxicity of most synthetic chemicals.

“The vast majority of chemicals in commerce have been tested either very little or not at all,” said environmental engineer Tom Young with the University of California, Davis. Young was not involved in the coho paper. “In the U.S., mostly we test a chemical because a manufacturer is concerned about their own liability from the chemical,” he said.

In an emailed statement, the U.S. Tire Manufacturers Association said its own studies have concluded that tire road wear particles – a mix of tire tread fragments and pavement bits – in sediment are not expected to harm freshwater or sediment-dwelling species.

“This recent local-level study in Washington State does not make a direct link between tire-related particles and impacts on salmon,” the statement reads.

The tire manufacturers’ association website also says that tires today are more durable than ever before—which means less tread rubs off into roadways and creeks for any given mile of driving.

Countering that trend, rubber is meeting the road more often. Central Puget Sound drivers put about 87 million miles a day on their vehicles last year, up 5 percent since 2010, according to the Puget Sound Regional Council.

Tires might appear to be a fairly simple product, made mostly of rubber. But chemically speaking, they’re anything but simple, according to Young. He calls tires “complex organic materials processed in complex ways.”

“We don’t even know what all those chemicals are,” he said. “We certainly don’t know what harm they do.”

Techniques ranging from pollution treatment plants to rain gardens can filter toxic pollution from stormwater before it reaches waterways. It’s usually easier and cheaper to avoid the pollution in the first place, whether it’s drips of oil or bits of tires.

To help car tires — and maybe our salmon runs — last longer:

- Make sure tires are properly inflated and maintained

- Drive less aggressively

- Drive less overall

Kolodziej said the road runoff that's killing coho salmon does not kill chum salmon or cutthroat trout in the same creeks, though less is known about harmful, non-lethal effects of the runoff.

"They're the canaries," Young said of the cohos.

“For a healthy Puget Sound we're going to need healthy urban creeks, and we're not there yet,” Kolodziej said.