Driest summer in a century offers taste of Seattle's future

You can only get to the lush rainforest of the Queets Valley on the rare occasions when it hasn’t rained recently and the Queets River isn’t too deep to wade across without being swept away.

But after western Washington’s driest summer in at least half a century, the river ran unusually low, and Olympic National Park's Queets Trail was easily approached: The river’s green water only reached this reporter’s shins as he waded across its slippery cobbles over Labor Day weekend under cloudless skies.

The U.S. Geological Survey’s river gauge showed the Queets flowing at about half its average levels in August, the lowest in 63 years of record keeping.

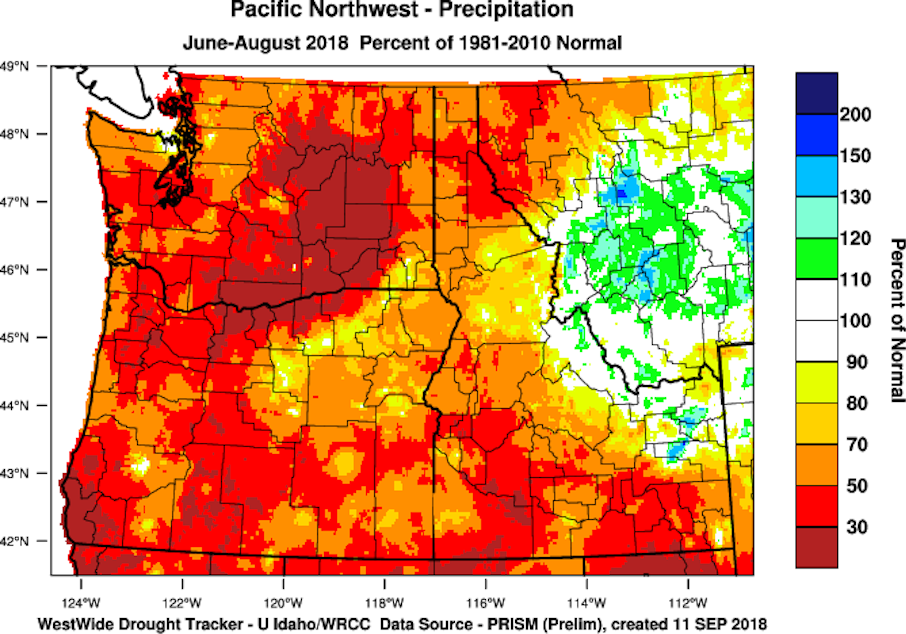

While summers are normally dry in the Northwest, unusual and in many places record-breaking weather left many Washington rivers running at less than half their normal levels in August, according to USGS.

It’s what the Northwest is expected to look like a couple decades down the road if we humans can't get climate change under control.

“It's the driest on record,” assistant state climatologist Karin Bumbaco said, referring to precipitation in the Puget Sound region from May through August, a measure that has been tracked since 1895. The region received just 2.5 inches of rain during those months, less than half the normal 7 inches.

This summer, weather stations from Bellingham to Olympia were as dry as they’ve ever been.

“It would be a pretty normal summer by the 2040s, 2050s, according to climate projections,” Bumbaco said.

As of Sept. 4, all of western Washington was experiencing moderate to severe drought, according to the National Drought Monitor produced by federal agencies and the University of Nebraska. Most of Oregon was experiencing severe to extreme drought.

Eastern Washington has had a drier than average summer, but not as pronounced as west of the Cascades.

Statewide, this May-August period was the third driest in 124 years of record keeping. Washington was drier only in 2003 and the Dust Bowl summer of 1938, according to Bumbaco.

She said at least the state had a good snowpack and a wet spring earlier this year.

"If you were to imagine this type of dry summer on the heels of not having that healthy snow pack that provides water resources for all the agriculture that occurs in eastern Washington, then we'd be in much worse shape," she said.

Reduced snowpack and warmer, drier summers could triple the acreage of forest fires in the state in the next 25 years, according to University of Washington climate scientists. Already, the Northwest’s fire season runs nearly four months when it used to be a few weeks in August.

Bumbaco said the Northwest’s recent dry summers have yet to rise above the natural noise of precipitation patterns varying from year to year, so it’s difficult to say how say much — if at all — human pollution is to blame. But she said the region’s rising temperatures do clearly display the fingerprint of industrial pollution.

“We are already seeing impacts of climate change here and now, so we should do whatever we can to stop that process,” she said.

Bumbaco, who has been working as a climatologist for a decade, said she grew more worried about climate change last year after she gave birth to her daughter.

“The year that she'll graduate high school is very well into where these climate projections that I look at on a daily basis [are],” she said. “Of course it concerns me for our future.”

KUOW environment reporter John Ryan loves getting tips and documents. He can be reached at jryan@kuow.org or on the encrypted Signal or WhatsApp apps at 1-401-405-1206 (whistleblowers, never do so from a work or government device, account or location). For greatest security, use KUOW's SecureDrop portal. Snail mail is also a safe way to reach him confidentially: KUOW, 4518 University Way NE #310, Seattle, WA 98105. Don't put your return address on the outside.