Endangered orcas missing from their home waters for 10 weeks

Southern resident killer whales haven’t been seen in their home waters for more than two months now. Researchers think the endangered orcas have gone elsewhere in search of a decent meal.

Southern resident killer whales are — or were — often found in the inland sea shared by Washington state and British Columbia.

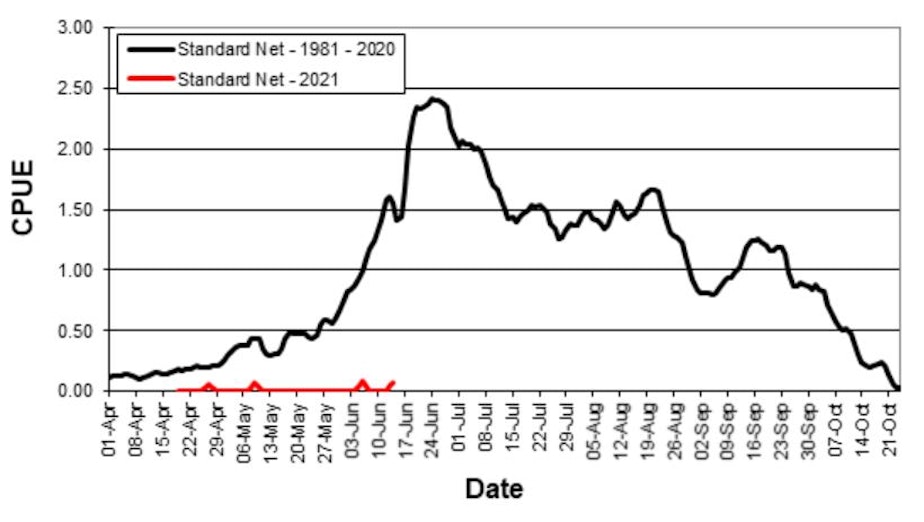

May and June used to be prime time for watching the fish-chomping predators in the San Juan Islands and other areas of the inland waters known as the Salish Sea. But in recent years, the southern residents have stayed away.

“There’s just not enough fish to pull them in here and keep them here for any length of time,” said orca biologist Deborah Giles with the University of Washington’s Center for Conservation Biology.

Other than a brief sighting of 10 orcas on June 7 around Swiftsure Bank, an area of open ocean off the northwest tip of the Olympic Peninsula, scientists and whale watchers don’t know where the endangered population might be. They were last seen in inland waters on April 10.

The southern resident orcas, a population that currently numbers 74 individuals, range from central British Columbia to California’s Monterey Bay.

Sponsored

“Hopefully, they are finding food out there,” Giles said.

Sponsored

It is the third year in a row that the orcas have abandoned their usual springtime habitat.

“Sadly, it does seem to be the new normal,” said Monika Wieland Shields with the Orca Behavior Institute.

While salmon streams on both sides of the border help sustain the orcas, researchers say Chinook salmon from Canada’s Fraser River are the endangered orcas’ most important local food source.

Most years, the Fraser produces more Chinook salmon than all the rivers of Puget Sound combined.

The large, fatty Chinooks that return to the Fraser River in the spring play an especially important role in the orca diet.

Sponsored

“They’re usually some of the biggest, most robust fish because they’re going further up the river. That’s why they return sooner,” Wieland Shields said.

Fraser River salmon runs have been in free fall in recent years. The Canadian government has listed 11 of 13 Fraser River Chinook salmon stocks as either threatened or endangered with extinction.

On June 8, Canada launched a US $535 million strategy to rescue wild salmon in the Fraser and other British Columbia rivers from the effects of climate change, habitat degradation and fishing pressure.

Sponsored

It is that nation’s largest expenditure for salmon to date.

"Many Pacific wild salmon are on the verge of collapse, and we need to take bold, ambitious action now if we are to reverse the trend and give them a fighting chance at survival," Bernadette Jordan, Canada’s Minister of Fisheries, Oceans, and the Canadian Coast Guard said in a press release.

Researchers and environmentalists have been urging governments on both sides of the border for years to do more to restore salmon populations.

Meanwhile, another type of killer whale, genetically and culturally distinct from the southern residents, is spending much more time in Puget Sound.

The “transient” orcas, numbering 500 or more up and down the West Coast, eat mammals, not fish, and the seals and sea lions they feed on are abundant in Puget Sound.

Sponsored

“Those guys are here much, much more often,” Giles said of the transients, also known as Bigg’s killer whales.

The southern residents got their name in the 1970s when Canadian researcher Michael Bigg confirmed that certain orcas spent much of their time off the southern end of Canada’s Vancouver Island, hunting for salmon headed for the mouth of the Fraser River, five miles north of the U.S.-Canada border.

The transients tended to wander the Pacific from Alaska to California.

“If those studies started today, we would be naming the mammal eaters the residents and the fish eaters the transients,” Giles said.

The 10 members of the southern residents’ L pod spotted by a team with the Center for Whale Research on June 7 included the female L25, believed to be the oldest of her kind at roughly 93 years of age.