Amidst racism inquiry, 'work to do' at Seattle Children’s

A committee reviewing issues of systemic racism at Seattle Children’s Hospital is asking current and former employees, as well as families with relevant information, to come forward. They say the identities of participants will be confidential.

The committee has tapped Eric Holder, former attorney general under President Obama, and his law firm Covington & Burling to lead the review.

The inquiry is the outgrowth of the resignation of Dr. Ben Danielson, a prominent Black pediatrician and administrator, from Seattle Children’s last November. His departure caused shockwaves and prompted letters, petitions and protests targeting one of the region's most prestigious healthcare institutions.

When Danielson resigned, he called Children’s an institution “replete with racism” in an interview with Crosscut. He cited numerous concerns from a lack of translation services, to staff dismissals and security practices affecting people of color.

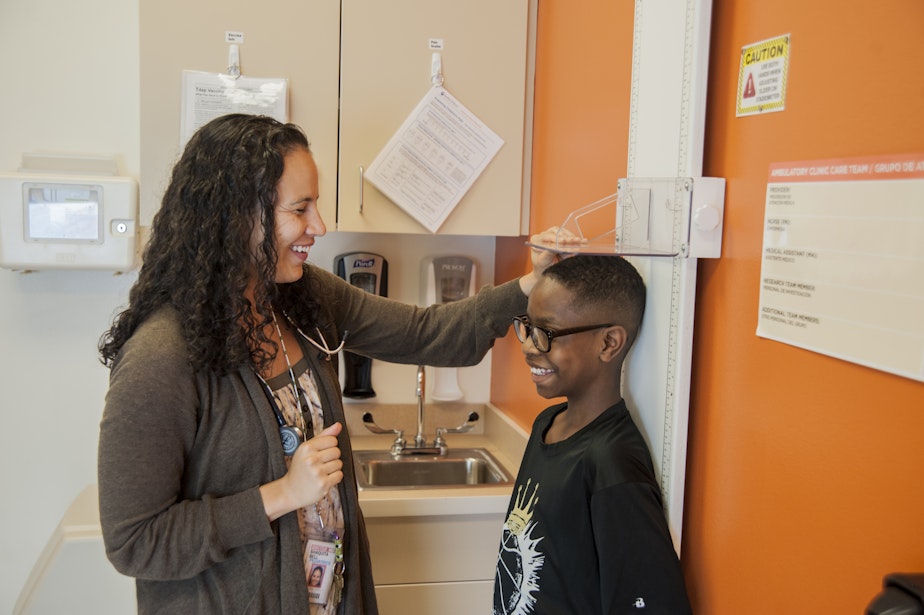

Danielson was the longtime medical director of the hospital’s Odessa Brown Children’s Clinic, which serves mostly low-income people and people of color. Danielson has accepted a new position with UW Medicine.

In the wake of his accusations, Children’s CEO Dr. Jeff Sperring wrote that he takes the issues of racism and bias seriously and “we have work to do.” Seattle Children’s formed an “assessment committee” comprised of trustees and community members to review “efforts to combat systemic racism, and to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion at Seattle Children’s, including the issues raised by Dr. Ben Danielson,” according to its website.

The committee has turned to Eric Holder, former attorney general under President Obama, and his law firm Covington & Burling to handle the review.

Holder posted a video statement on the committee’s website saying: “We were hired to conduct an independent and objective review of Seattle Children’s policies and practices, to make findings, and to propose recommendations.”

Sponsored

Seattle Children’s board trustee Colleen Fukui-Sketchley chairs the assessment committee. She said the committee hopes to deliver findings and recommendations to the hospital’s board before the end of June.

“While there’s no deadline to provide information to the committee, it is helpful for us to receive it sooner rather than later,” she said.

Danielson has criticized Seattle Children’s response to his departure. At an appearance in February he said “If there’s been hospital theme throughout this process, it has been power-hoarding: wanting to control the message and the process, creating the illusion of engagement.”

Eric Holder’s team will likely be hearing from people like Sakara Remmu. Remmu is the former chair of Black Lives Matter Seattle-King County. Danielson was her children’s pediatrician. In the wake of his departure, she’s written about her son Khabir who was three years old when he died of cancer at Seattle Children’s in 2005.

Sponsored

She said Khabir’s diagnosis and treatment were delayed because Danielson was overruled by a white emergency room resident who dismissed Khabir’s symptoms.

“It wasn’t about malicious intent,” Remmu said. “It was about upholding white supremacy and an inherent, internalized belief that Black people couldn’t possibly know better. “

Remmu said to build community trust, the outside review should culminate in a public assessment of Seattle Children’s practices along with data, examples, and narratives. She said Eric Holder’s name alone is no guarantee of results.

“I do not feel internally within myself that they are fully committed to addressing these issues,” she said. “[Holder] has received a contract; we don’t know what’s in it. Are you using that name to exonerate yourselves at the end of the day?”

Remmu sued Seattle Children’s for discrimination. As part of their legal settlement she had to sign a nondisclosure agreement about the specifics of her case. She’s called on Seattle Children’s to release other families from any nondisclosure agreements so they can contribute to the inquiry. The hospital has agreed to do that.

Sponsored

Remmu said her settlement included the provision that Khabir’s portrait be hung both in the hospital and in the Odessa Brown Children’s Clinic.

“Because well before Khabir died it was very clear what was happening, they knew what was being done to my family,” she said. “I did not want them to forget Khabir.”

Remmu said her experience was more painful knowing that her grandmother had blazed the trail to racially integrate her nursing school and the staffs of local hospitals where she worked just decades before. Remmu said healthcare institutions “let that vine dry and die” without fostering Black staff and administrators. Danielson said he felt isolated as one of the few Black physicians in a leadership position.

“This is the moment to truly advance culturally responsive medical care,” Remmu said. “The only way you can achieve that is by owning, addressing where you have failed to do so in the past.”

Sponsored

Dr. Shaquita Bell replaced Danielson as interim medical director of the Odessa Brown clinic. She’s also the medical director for the hospital’s Center for Diversity and Health Equity.

Bell said she sees Khabir’s portrait every day at Odessa Brown and it is “beautiful.” She said, “It is a lesson for us in what we can do better.”

Bell also calls Danielson a mentor. She said she begged to be placed at Odessa Brown as a resident when she came to Seattle in 2006.

“We’re inspired as well as being sad to lose his guidance and his leadership,” she said. “We’re also inspired by his words and his actions over the last 20 years to continue to work for equity and to continue to be anti-racist in very tangible, very specific ways.”

Sponsored

Bell said she is working to address his concerns along with the challenges brought by the Covid pandemic.

“While I do believe and see and witness the consequences of systemic and institutional racism on a daily basis, I also get to see and feel the difference I can make in those systems” she said.

Bell said one focus has been rewriting hospital policy in handling “code purple” situation (when the patient is deemed to pose a danger to themselves or others) to rely more on mental health professionals and social workers when patients are in distress.

“Or do they need security, do they need police, are they truly a danger to themselves or others. So just enacting that policy, changing that policy, was groundbreaking,” Bell said.

She said she’s also trying to revitalize community and patient involvement at Odessa Brown, a clinic that was founded in 1970 thanks to community advocacy.

“At some point along the way, and maybe it predates me, but that role for the community started to sort of become smaller and smaller,” she said.

Bell said they’re holding a listening session with community members May 22 to present and take feedback on the hospital’s anti-racism strategic plan.

Meanwhile in Seattle, there’s an effort to launch the region’s first community clinic focused on the healthcare needs of Black people.

Danisha Jefferson-Abye is the founder of The Tubman Center for Health & Freedom.

“Black people experience some of the worst health outcomes in the country,” she said. “The fact that there’s not a healthcare clinic specifically designed with their needs in mind is troublesome.”

Jefferson-Abye signed a community petition in support of Danielson, and said the elements of Seattle Children’s anti-racism strategic plan constitute “a great list” but she’ll be waiting to hear more about implementation.

“We often don’t see the actual, tangible results of change,” she said. “Reforms can soften blows but certainly at the Tubman Center we believe we’re going to have to design an alternative system from the ground up.”

She said the Tubman Center is expected to open by 2025. Odessa Brown is also scheduled to open a second clinic in Seattle’s Othello neighborhood next spring.

Correction 11:47am 4/26/21: An earlier version of this story said that Dr. Danielson did not respond to interview requests, that was incorrect. More recently he told KUOW the most meaningful findings from the inquiry by Seattle Children's should involve sunlight, transparency, and non-retaliation against people who raise concerns. He said, "For communities most impacted by racism and inequities in healthcare outcomes, measures that truly shift power in terms of the ability to see what's happening and have leaders be accountable to them -- that's how you see tangible change." Danielson added that he's struck by the community support he's received after leaving Seattle Children's. He said, "The power of love in this community is really incredible. That makes faith for me in people's ability to create a different society."