How Will The U.S. And WHO Fare Without Each Other?

Last week, President Trump declared that he is "terminating" the decades-long U.S. relationship with the World Health Organization over the agency's relationship with China and withdrawing U.S. funding.

But it's unclear what will happen next — and what the short- and long-term implications will be.

Global health experts are scratching their heads. "It's still kind of murky," says Jeremy Konyndyk, senior policy fellow at the Center for Global Development and former U.S. Agency for International Development official in the Obama administration. Konyndyk is just not sure how things stand: "whether the U.S. is now officially out and we've lost our vote or whether there's a cooling-off period while we work through the issues."

"The devil will be in the details," wrote Ilona Kickbusch, founder of the Global Health Center at the Graduate Institute Geneva, in a tweet. "What is the timeframe? The legal situation? Will Admiral [Brett] Giroir [the U.S. representative to WHO's executive board] who just presented his credentials to @who Executive Board resign? Will US agencies not be allowed to work with @WHO?"

So far, the Trump administration has not shared the details of its plan.

Sponsored

NPR asked for clarification. A spokesperson for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which serves as the U.S. representative to WHO, referred NPR to the president's May 29 remarks. Asked about the impact on ongoing work between the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and WHO, a press officer wrote via email: "Please reach out to the White House press office for assistance with this inquiry."

The White House declined to comment.

Still, there are direct consequences if the U.S. stops funding and cooperating with the U.N. agency tasked with coordinating global responses to health threats, including the COVID-19 pandemic. Here's what could happen in the short, medium and long term:

Short-term reactions

It's not even clear an instant withdrawal is possible.

Sponsored

To leave the organization formally, the U.S. is supposed to give a one-year notice and pay outstanding dues, according to language that the U.S. added to the WHO constitution when signing the treaty in 1948. As of April 30, the U.S. owed $198 million in unpaid membership dues.

Whether Trump intends to exit the organization formally or just stop participating is an open question, says Felicity Vabulas, assistant professor of international studies at Pepperdine University, who studies how countries leave global organizations.

So far, WHO's public response has been to brush off Trump's comments. "It is WHO's wish for this collaboration [between the U.S. and WHO] to continue," Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the agency's director-general, said in what has so far been its only response to Trump's announcement, at a press conference Monday. Tedros offered no further comments when pressed.

"A dignified silence from Geneva" is how Kelley Lee, a global health professor at Simon Fraser University, characterized it.

"Ignoring an empty threat" is how Clare Wenham, assistant professor of global health policy at London School of Economics, described it.

Sponsored

Wenham's read on WHO's current strategy is that it hopes to wait Trump out. If he loses the election in the fall, she and other global health experts say they think a new incoming president would likely reestablish the working relationship between the U.S. and WHO.

Vabulas says this wait-it-out strategy has worked before for the United Nations. In 1965, Indonesia told the U.N. that it was leaving the organization over a conflict with Malaysia. "Then there was a government turnover, and they basically came back and said, 'Actually, we didn't really want to do that. And the U.N. said, 'Well, we never really treated it like it was real anyway."

"So maybe," Vabulas says, "there is a strategic reason to just stay mum right now."

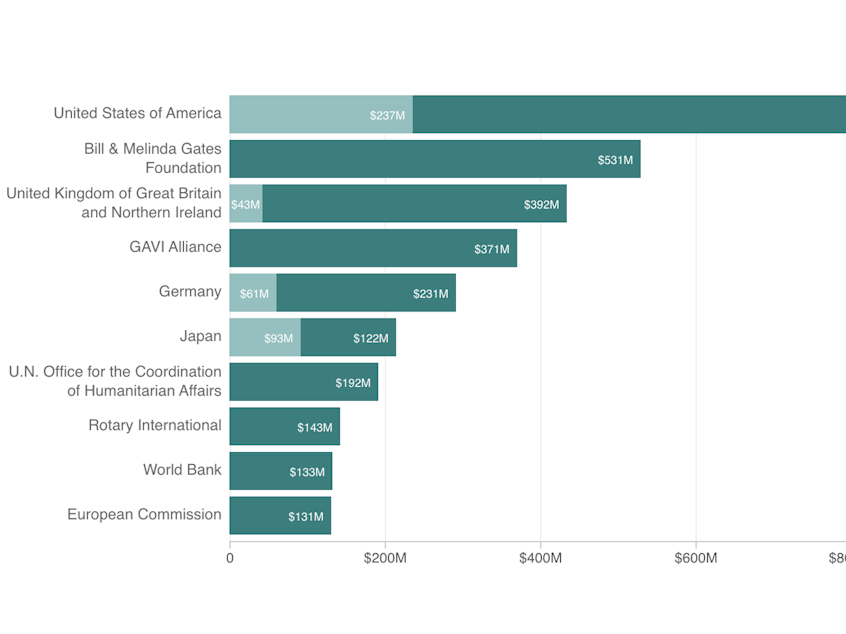

Meanwhile, as the U.S. funding freeze continues, WHO faces potential funding shortages in its operational and COVID-19 response budgets. The U.S. is WHO's top funder and contributes around $450 million each year, covering about 15% to 20% of the agency's budget.

Other countries and contributors are stepping up to cover the shortfall, Wenham says.

Sponsored

After Trump first announced a U.S. funding freeze in mid-April, China pledged an additional $30 million to WHO's coronavirus response, about the same amount the U.S. initially donated to the efforts. China has since pledged another $2 billion over two years for WHO's coronavirus fight.

It's not just China that's pitching in, Wenham says. European countries have upped their contributions, as has the Gates Foundation, which is WHO's second-largest funding source (and also a funder for NPR and this blog).

Midterm possibilities

One possible explanation for Trump's abrupt announcement is that it's motivated by politics. Kickbusch, for example, theorizes that he hopes to shift blame for the nation's rising COVID-19 numbers away from his administration and onto China and WHO in a bid to attract votes for November's presidential election. "Some people are thinking that, should President Trump be reelected, the focus on WHO might not be quite as important as it is right now, and he might be more amenable to a deal," Kickbusch says.

But if the U.S. does indeed permanently pull its representatives from the organization, it will cede its seat at a very important table. "The U.S. has been at the forefront of developments of global health policy and developing the World Health Organization since it started," Wenham says. "They've been able to direct global health policy to map onto U.S. interests," which have been largely focused on issues that could threaten the health and safety of Americans as well as select infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis and polio.

Sponsored

This could mean that global health priorities the U.S. has invested in significantly could suffer major setbacks, Lee says. For instance, the U.S. has worked for decades to rid the world of polio and the wild virus is circulating in just two countries: Afghanistan and Pakistan. Last year, WHO released a five-year polio endgame plan to eradicate the disease fully, to which the U.S. contributed significant funding and expertise. If that support is withdrawn, Lee says she believes that the result will be a drop in the number of children who are vaccinated.

Trump has said the U.S. will continue to fund such global health priorities and funnel the money to partners other than WHO — but Lee predicts that the work will still be significantly disrupted. "These are not regions of the world that you can just walk in and roll up somebody's sleeve [and give a shot]," Lee says. "You have to build relationships. You have to have trust from local communities. It takes years and years to establish a program."

Konyndyk agrees that WHO plays a role that charities and nongovernmental organizations can't replicate. "There are many, many countries in the world that lean on WHO as an extension of their own health ministries," he says, particularly developing nations with limited resources that trust WHO to provide credible advice and guidance. "WHO is inside the tent with the health ministry in a way that no NGO will ever be."

The potential shifts and setbacks to WHO's work as a result of a U.S. exit will be unfortunate not only for other countries but for the U.S. as well, Konyndyk says: "[WHO] serves U.S. interests by enabling other countries to better deal with their own health problems and to prevent those from becoming global problems."

Long-term impacts

Both WHO and the U.S. could face serious consequences, according to the specialists interviewed.

Some countries may follow the U.S. example and leave WHO "if they agree with the U.S. that WHO is messed up [in being too influenced by China] or is not serving their best interests, or there's pressure on them from the U.S. to follow suit," Wenham says. Such moves would weaken WHO's global authority considerably.

The U.S. could also find itself isolated and having less influence in global affairs, Konyndyk says. Countries could be reluctant to ally with the U.S. if they don't believe the country is good on its word, Vabulas says.

The fragmentation of global health authority could set the world back a century, to pre-World War II times when there were several competing international health groups in Europe and the Americas, says Lawrence Gostin, director of the O'Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University.

"We could end up having one [international health branch] being led by China through its Belt and Road initiative, one through Europe and Africa with the World Health Organization and the United States using its own channels like PEPFAR or the Global Fund," Gostin says.

Then global leaders would likely relearn the value of having a unified global health body such as WHO — and form it again, Lee says.

She sees two possible paths the world could follow. In one scenario, countries continue to isolate, and restrictions imposed by various health authorities lead to less opportunity for travel and trade and for working multilaterally on health issues, which spread across borders no matter what.

The alternative is to learn from this experience and work to fix the systems we have, she says: "If we want to be going back to a world where we're interconnected, we need global health governance to underpin that." [Copyright 2020 NPR]