I was a 'library kid.' But my old school is among many in WA that no longer have librarians

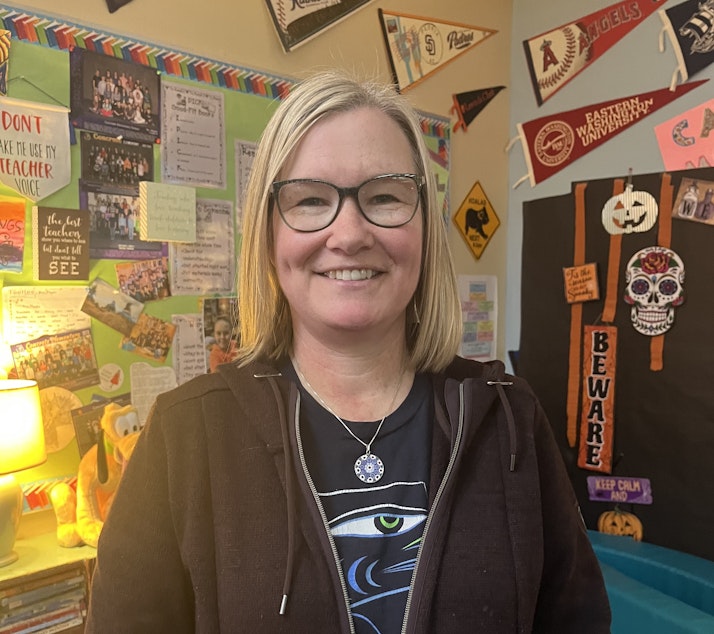

For more than a quarter of a century, Laura Moffitt dedicated her career to the elementary school library in the rural Washington town of Concrete. A lot of that time was spent trying to save it.

I

got to know “Miss Moffitt” when I was one of the 300 students she says passed through the library doors each week. She shared her love of reading with all of us.

“I just love it. I mean, I like to read myself, a lot of different genres,” she said. “Some of it just takes you to a place that you wouldn’t even be able to imagine otherwise.”

I loved it, and so did the other kids. Moffitt recalled that many of them told her it was their favorite time of the week.

But in recent years, things began changing.

Sponsored

When Moffitt first began working at the district, there were three libraries at the high school, middle school, and elementary school levels.

The middle school library closed first. All of those books went into the other two libraries.

A few years ago, the high school library reduced its hours. Administrators moved shelves of books out to make room for a counselor’s desk.

“And that’s when I realized something was going on,” Moffitt said.

Moffitt wrote letters to the school board, superintendent, and others with influence in the school. She was told not to discuss the issue.

Sponsored

By last year, Moffitt was the only librarian in the district, and she learned the same thing that happened at the high school would be done to the elementary library.

“That’s when I decided that it was probably a good time to retire,” Moffitt said. “It was a 25-year process of watching it just go down.”

In her letter of resignation, Moffitt begged school officials to hire a new librarian. They didn’t.

Before she left, Moffitt made a video explaining to teachers how to check out books to students using the school’s online catalog.

But most teachers are stretched too thin to take advantage, so kids aren’t checking out books. And there’s no one to reshelve them, anyway.

Sponsored

Renata Mapes teaches at Concrete Elementary, and was my fourth grade teacher. She says many students don’t even realize what they’re missing, comparing them to “a fish that lives in a tiny little bowl.”

“They may not know that they could live in a bigger bowl,” Mapes said. “They just get used to the little bowl.”

Mapes says the school isn’t the same without Moffitt.

“It’s hard to do on our own with no central person holding it all together,” Mapes said.

Sponsored

The situation in Concrete isn’t unique. A rising number of schools across the state and country don’t have librarians.

It comes as many schools — both urban and rural — grapple with big budget shortfalls. It’s part of a national trend, fueled by declining enrollment. Because schools are funded based on the number of students they serve, less money is coming into districts.

Seattle Public Schools, for example, has lost nearly 5,000 students over the last five years. That’s resulted in about $81 million less revenue for the district, and next year, the district faces a budget deficit of about $105 million.

District leaders in Seattle and across the state are now looking for ways to cut costs, from closing schools and canceling programs to laying off teachers and staff — like school librarians. In 2019, even before Seattle’s massive budget shortfalls came to a head last year, district librarians were fighting for their budget.

And that’s what happened in Concrete, where enrollment has dropped by nearly 10% over the last decade.

Sponsored

This trend has school librarians and advocates like Ryan Grant concerned, especially because research shows children who cannot read proficiently by third grade are less likely to graduate on time.

“Everything we know about literacy research says that getting kids books that they can engage with on their level, that they want to see, that give depictions of their lives, that give them windows into other worlds — that’s when you hook them on literacy,” said Grant, a school librarian just outside Spokane. “That’s when you hook them on reading.”

As the legislative chair of the Washington Library Association, Grant is part of an effort to ensure all schools across the Evergreen State have strong library programs.

While Washington state allocates money to all districts for school librarians, Grant says the state doesn’t strictly require that schools use the money for that.

Grant says the association is trying to change that with a new law. The association was unsuccessful in their efforts last session, but Grant says they’re not going to let up — although they understand schools are in a tough spot when choosing what to cut.

“On one hand, you know, I agree that districts need to prioritize and make the right choices for them,” Grant said. “On the other, I’m a librarian and I think districts need these positions and kids need access to school libraries that are staffed appropriately to meet their needs.”

Grant says it’s also an equity issue.

About two-thirds of Concrete students are considered low income, and economically disadvantaged students are less likely to have access to quality reading materials.

At Concrete Elementary, Mapes says she sees that firsthand.

“Some kids are members of the town library or the city library, but again, that’s something that really involves parents and not all kids have parents that are able to get them to the library,” Mapes said. “School libraries are sort of that one equalizer.”

Concrete Superintendent Carrie Crickmore called the elimination of Moffitt’s position a “funding issue,” and said the district is looking into “creative methods to ensure students have access to library books and services.”

One of those methods is a new partnership between the local library and the schools, which will allow students to check out books through their online catalog.

But it’s not the same experience as going to the school library.

When I went to Concrete, I was a library kid. I’d spend hours reading there after school. To me, it was a pathway to the world. I remember begging Miss Moffitt to let me check out more than five books.

“Having that access to be able to, I don’t know, just use your imagination and go anywhere you want,” Moffitt said. “You know, I just love it.”

Since she retired, Moffitt hasn’t gone back to the school.

“I haven’t had the heart,” she said.

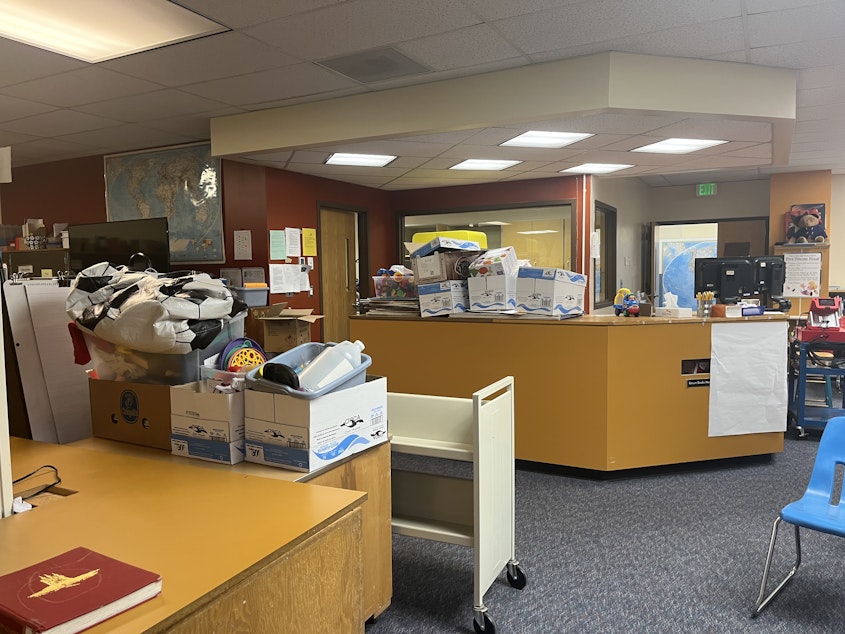

These days, Concrete’s library is mostly used for storage and meetings. The walls are bare, and the desk where Moffitt used to check out books is now filled with boxes.

--

This story was co-reported and co-produced by KUOW Education Reporter Sami West and RadioActive Youth Media. Production support by Lila Lakehart.