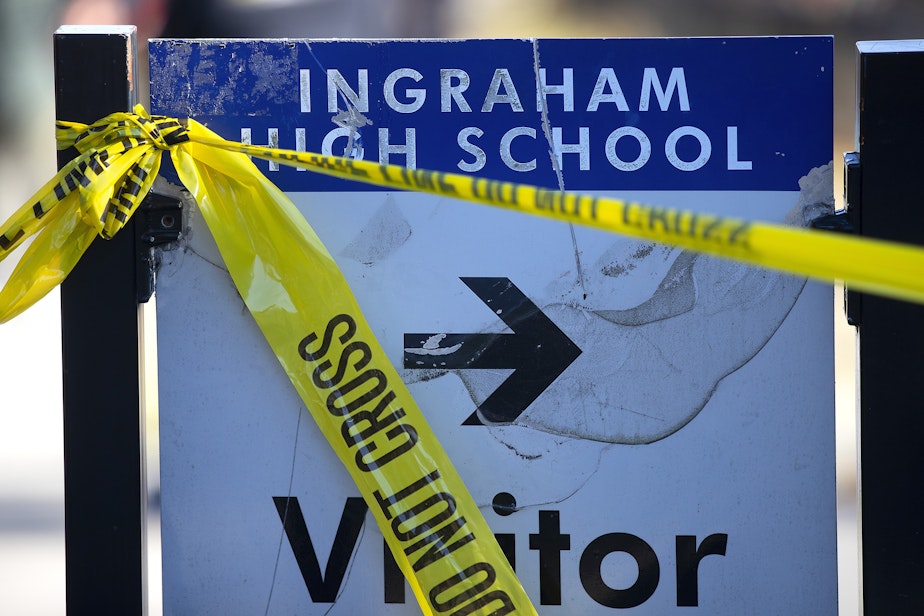

Judge bans gun access for Ingraham student 'mentally preparing' for Eastside school shooting

King County Superior Court Judge Samuel Chung prohibited a student at Ingraham High School from purchasing or possessing firearms Tuesday, after the student told a psychologist he was mentally preparing to commit a school shooting on the Eastside. However, the student’s father declined to hand over his own firearms to police for safekeeping, saying he stores them in a safe in their Shoreline house.

KUOW is not naming the 18-year-old student, who has not been charged with a crime.

Seattle Police first sought an extreme risk protection order under the state’s red-flag law on Nov. 17, after the student told a psychologist that he intended to conduct a school shooting, targeting students as they changed classes to maximize the number of victims, and gauged his own readiness at an “8” on a scale of 1 to 10.

He told the psychologist he had spoken to a friend about acquiring a semiautomatic assault rifle, which is restricted to purchasers ages 21 and over. That psychologist then alerted Seattle Police.

Washington voters passed the initiative creating extreme risk protection orders in 2016, and new age restrictions to purchase semiautomatic firearms in 2018.

Seattle Police Officer Sandlin Grayson testified during a hearing about the protection order that he and a mental-health professional with SPD’s Crisis Response Team interviewed the student after the psychologist’s report.

Sponsored

Grayson said the student disclosed that he was a student at Ingraham High School in north Seattle “and the murder of Ebenezer Haile had impacted him significantly because they were in a class together and they were acquaintances or potentially friends.” (Two students are facing criminal charges in Haile’s death after he was shot and killed at the school on Nov. 8.)

The student told SPD he previously lived in Bellevue until last summer, and that during that time he was bullied by students from Sammamish High School while attending a different school there. His family later moved to Shoreline and the student transferred to Ingraham.

According to Officer Grayson, the student said he wanted to kill “a multitude of students” at Sammamish High School. Grayson said the student told him he “realized he didn’t need to specifically target those who had bullied him at Sammamish High School. That if he was to kill others, he knew those who had bullied him would feel the same pain or anguish knowing their friends had been killed as he had felt at the death of Ebenezer Haile.”

Grayson said the student “told me he has had a history of thinking about conducting mass killings.” In fact, just a few weeks before, the same student had told a different therapist that he wanted to place a bomb on I-5 so that vehicles would fall into the water off the Ship Canal Bridge. That therapist also reported that threat to SPD.

Grayson said SPD concluded that the student "had taken no steps that the Seattle Police Department is aware of to acquire a firearm." But Grayson said allowing the student to have access to firearms gives rise “to a reasonable fear of future dangerous acts.”

Sponsored

Grayson told the judge he was present when the student was served with a temporary extreme risk protection order on Nov. 17. The student “said he understood what it was and he commented – this is his quotes – ‘This is really helpful to know that I couldn’t get anything even if I wanted to.’”

Grayson added, “So it was my interpretation that he took some reassurance knowing that even if he felt a desire to go acquire a firearm, he would be prevented from doing so by the existence of the court order.”

Judge Chung said he agreed with police and prosecutors that the student would pose a significant danger to himself or others if he were allowed access to firearms. His approval of a permanent order means that the student is banned from having or purchasing firearms for the next year. The order could be renewed in the future.

But Kim Wyatt with the King County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office, which sought the protection order, acknowledged another concern: the student’s father owns firearms which are not affected by this order. Officer Grayson said when they served the initial order, “the Seattle Police Department offered to store those firearms in our evidence unit for the safety of the family. The father declined as he is the owner of the firearms” and told police he keeps them "in a high-security safe” that he said the student cannot access.

Wyatt asked the judge to order a compliance hearing in the near future in which the father could provide more details to the court under oath about how his firearms are secured.

Sponsored

“We would ask the court to ask the parents or whoever’s living in that home, one, are they willing to safely store their firearms offsite, away from the access of anyone who’s subject to a court order,” Wyatt said.

She said the court has been able to reach agreements with family members about the safe storage of firearms in all but a handful of cases, out of an average of 70-80 extreme risk protection orders each year. But if they could not reach a consensus, she said there could be a question of whether the subject of the protection order could remain in that setting with access to firearms.

Chung agreed to order a compliance hearing, and a behavioral health evaluation for the student. Neither the student, his family, nor anyone on his behalf attended the court hearing.