More intense winter storms forecast for Northwest

Wintertime is often drizzle time in the Pacific Northwest. The region may need to get used to more intense rain — and landslides and floods — as our climate changes.

A new study predicts that extreme downpours could quadruple in frequency in the Northwest by the end of the century as the global climate changes.

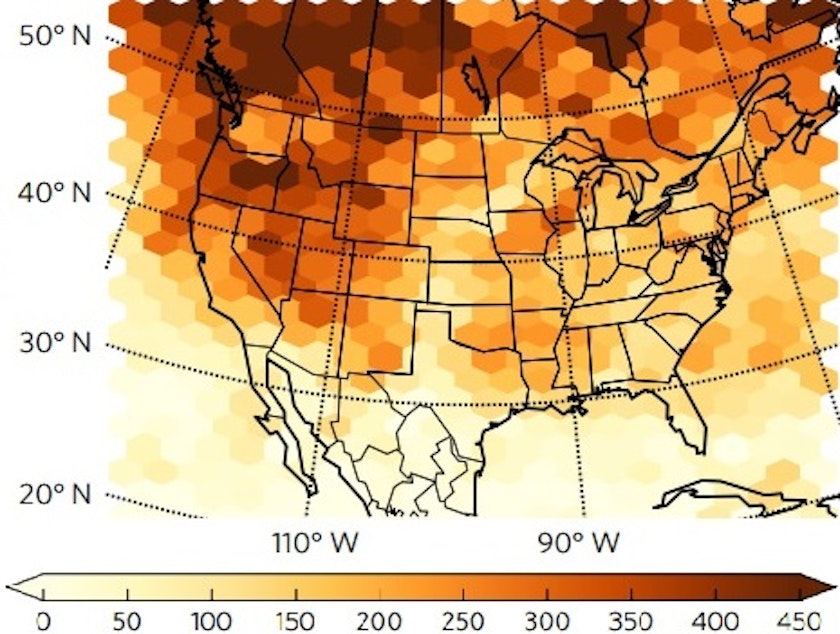

The study from scientists at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, forecasts similar increases in intense rain events across much of North America if the world's emissions of heat-trapping gases continue unabated.

In the eastern United States, the biggest jumps in extreme rainfall would come in the summer.

Here in the Northwest, the researchers expect that quadrupling of extreme storms to come in the winter.

Sponsored

"The Pacific Northwest is really in the hotspot," lead author Andreas Prein said. "In the Pacific Northwest, you have much higher frequency increases than in rest of country, at least in wintertime."

Prein said under a high-end scenario of unabated emissions and global warming of 4 to 5 degrees Celsius, the Pacific Northwest would see its heaviest storms dump one-third more rain per hour and arrive 4.6 times more frequently each winter.

With a warmer climate, the storm systems known as atmospheric rivers or Pineapple Expresses would be able to carry more moisture to the Northwest from the tropical Pacific.

Wintertime is when heavy rains help turn Northwest hillsides into Northwest mudslides.

"They certainly are going to cause more landslide events and debris flow events in creeks," geologist Dan McShane of Bellingham said of increased winter downpours.

Sponsored

Waterlogged soils are more prone to sliding apart.

McShane said the deepest landslides, like the one that killed 43 people in the town of Oso, Washington, in March 2014, are triggered by much longer-term precipitation patterns than the NCAR study looked at.

"Oso was really deep," he said. "That takes 2 or 3 years of really wet weather."

The NCAR study did not address how a changing climate might alter where storms go.

"The question is where will the atmospheric river be aimed," McShane said. "Will climate change cause it to be aimed more here, or Oregon or British Columbia?"

Sponsored

As a consulting geologist, McShane evaluates landslide risks for a living.

He said wherever atmospheric rivers land their heavier liquid loads, there are going to be more landslides.

"I could say it's good for my business," he said. "I hate to say it, but it's true."

Water woes

Extreme downpours can also cause problems by overwhelming sewage systems and by flushing everything from sediment to salmon eggs out of streams.

Sponsored

That sediment in turn would worsen the risk of flooding -- by filling in the spots in streams and rivers where water used to go.

A Pineapple Express in January 2009 caused widespread flooding in western Washington and $125 million in damages; 30,000 people had to evacuate.

Besides causing flooding, runoff following storms is one of the biggest sources of pollution into Puget Sound.

But toxicologist John Stark with Washington State University said the amount of rain matters less than the amount of motor oil, brake dust and other gunk left on roadways.

"It's really the volume of traffic," Stark said. "Increasing rainfall might not have as big an effect as an increase in the number of people moving into the area and driving more vehicles."

Sponsored

Reducing that volume of traffic would cut down on the gunk going into Puget Sound and the carbon dioxide going up in the sky.

Scientists say it will take deep cuts in the world's emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases to avoid the worst impacts of a changing climate.

The NCAR study appears in the journal Nature Climate Change.