New Seattle CHOP videos contradict city’s narrative in unsolved killing

New records and videos released ahead of a Nov. 3 trial appear to contradict Seattle officials’ and protesters’ narratives about the unsolved killing of a Black teenager that led to the end of the Capitol Hill Occupied Protest.

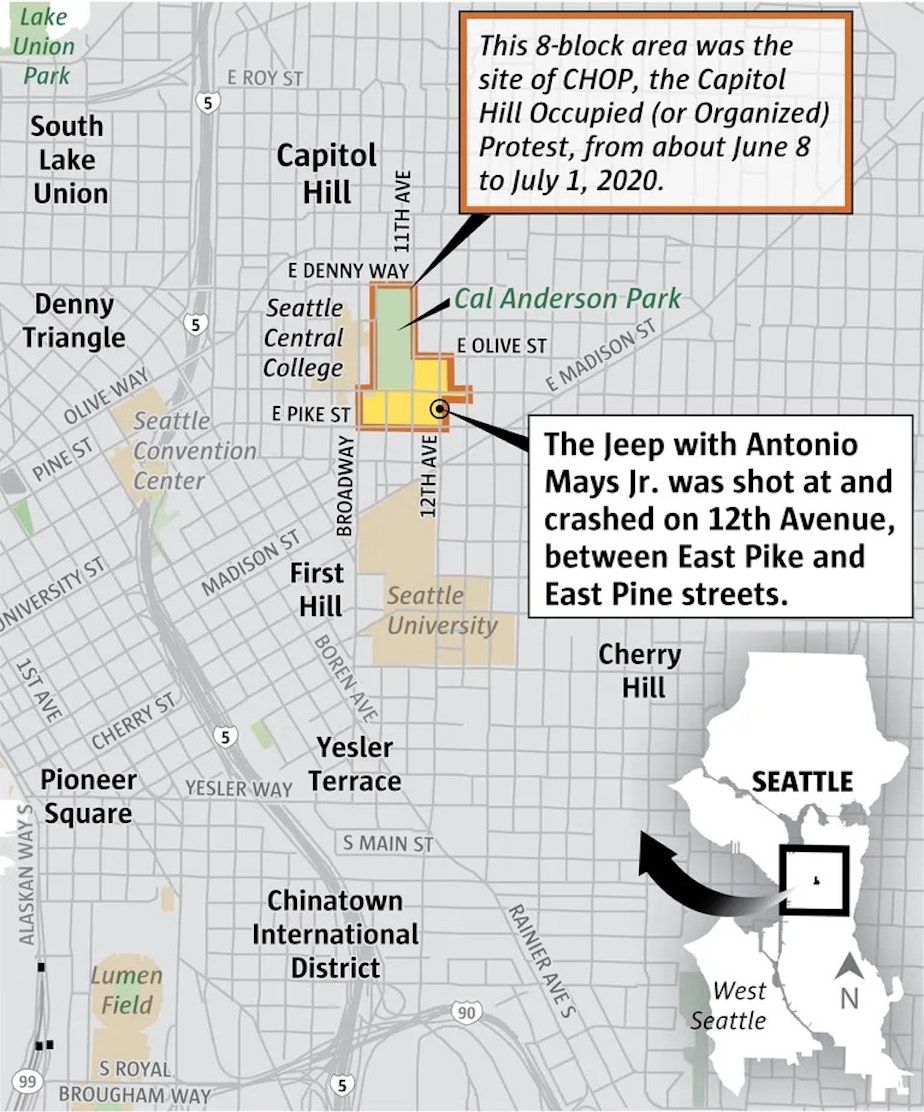

Significant questions about the death of 16-year-old Antonio Mays Jr. remain an unhealed wound from the summer of 2020, when police blasted protesters with crowd-control weapons, clouds of tear gas rolled through residential neighborhoods and hundreds of activists, gawkers, unsheltered people and thrill-seekers occupied eight square blocks of Capitol Hill after officers abandoned the department’s East Precinct.

And CHOP’s impact continues to reverberate on a national level, as the Trump administration conjures images from Seattle streets in 2020 to justify the presence of federal troops in American cities today. In a September meeting with U.S. military officials, Trump evoked his threat to intervene in Seattle in 2020 to suggest American cities might serve as “training grounds” for the military.

The last moments of Mays’ life were spent racing away from Seattle’s CHOP protest zone in a silver Nissan Pathfinder, as three people, with a fourth hanging onto the roof, frantically drove the mortally wounded teenager toward medical care.

Mays’ father said he filed his lawsuit against the city of Seattle in 2023 to push for more information about his son’s killing after updates from police stalled. Antonio Mays Sr. and his attorney allege that the city’s negligence in its emergency response led to Antonio Jr.’s death. The lawsuit requests unspecified damages.

Sponsored

City lawyers have argued that Seattle bears no legal responsibility for what happened to Mays because, they say, he was shooting a gun out of a Jeep he stole when he was shot, citing a protester who was livestreaming from CHOP.

But hundreds of pages of newly released records obtained from King County Superior Court provide the most detailed account of the events leading up to and after the shooting — and many do not support the city’s version of events. A video analysis commissioned by the city suggests that gunfire in the minutes before Mays was killed was aimed at the vehicle Mays was in.

These documents could be the last the public sees of new information about Mays’ killing if the judge grants the city’s request to throw out the case, unless Seattle police name a suspect and prosecutors bring the case to trial.

Here are the four biggest revelations from the new records.

1. A familiar SUV

Sponsored

Shots had been fired at Mays from the same Nissan Pathfinder that carried him to medics minutes later.

The same silver Pathfinder that attempted to rescue Mays after he was shot had been carrying people who just minutes earlier were shooting at the Jeep he was in, according to a video analysis released as part of the city’s motion for summary judgment.

The video analysis, commissioned by the city and conducted earlier this year by traffic accident reconstructionist William Neale, shows at least two people inside the Pathfinder open fire on the white Jeep that carried Mays and another teenager through the empty early morning streets of Capitol Hill.

Nothing in the video analysis — which looked at eight different videos leading up to the fatal shooting — shows gunfire coming from the white Jeep.

Mays was killed on a chaotic night, after CHOP had gradually grown more disorganized and a diminished group of protesters, volunteer security, unsheltered people and partyers remained. Witnesses that night recounted multiple instances of gunshots and fireworks ringing out and multiple vehicles driving around erratically, adding to an atmosphere of confusion and panic.

Witnesses have given contradictory accounts of whether someone in the white Jeep was shooting. To date, no video has emerged showing anyone in the vehicle holding a gun or firing.

The most widely cited evidence that someone in the Jeep was shooting comes from a livestream in which a protester narrates as shots ring out.

“A car has been circling around shooting more shots into tents,” the protester says.

The white Jeep is not visible in the livestream at that moment, and no reports later emerged of anyone struck or any tents damaged by gunfire from the Jeep.

Sponsored

Nevertheless, Seattle city attorneys cited this protester’s livestream to argue the city wasn’t liable for Mays’ death because he was shooting from the Jeep — committing a felony — when he was killed.

A spokesman for the Seattle City Attorney’s office declined to comment, citing the continuing litigation.

The newly released video analysis suggests that gunfire in the minutes leading up to Mays’ death came from people shooting at the Jeep carrying the teens.

Additionally, lead homicide Detective Alan Cruise “testified under oath that Antonio Mays Jr. and (survivor Robert West) were victims who fired no shots and committed no crimes,” according to an Oct. 15 motion filed by Mays Sr.’s attorney, Evan Oshan.

Witnesses said “CHOP security” was responsible for the shooting of the two boys, and some supportive of the protest online even praised the shooters for their marksmanship and for stopping what they perceived to be a threat.

Sponsored

RELATED: Seattle CHOP killing: Lost evidence, official secrecy, a note home

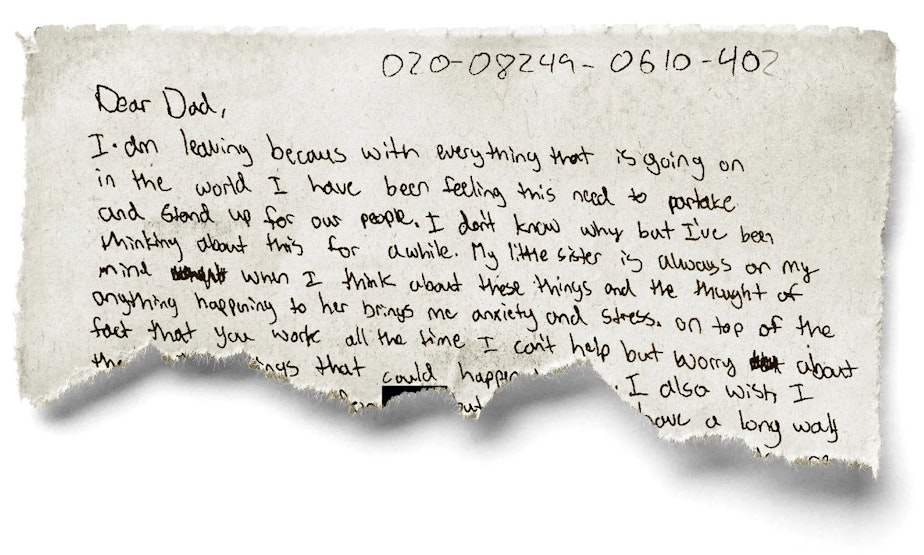

Mays, who was born and raised in Southern California, had been in Seattle for just eight days, drawn to the protest zone. He’d left a note for his father saying he felt “this need to partake and stand up for our people.”

It’s unknown who was inside the Pathfinder — also reported stolen — shooting at Mays and 14-year-old West, another occupant of the Jeep, though a video shows someone in a white shirt or hoodie firing what appears to be a handgun at the Jeep from the Pathfinder’s rear passenger window, while another person in a gray hoodie shoots a long gun from the front passenger-side window.

Sponsored

It’s unclear whether the boys were hit by bullets fired from the Pathfinder or in a separate volley of gunshots that erupted minutes later, after the Jeep crashed into barriers set up by protesters on 12th Avenue.

2. Who was driving?

There’s reason to doubt Mays was driving the Jeep.

The city contends that Mays was driving the Jeep. However, a protester who transported Mays to medics that night told The Seattle Times that Mays had been in the passenger seat. Another protester told city attorneys and Oshan the same thing.

Mays’ autopsy shows almost all his wounds were on the right side of his body, suggesting that bullets entered from the side that was exposed to the passenger-side window and door.

As part of its defense against the lawsuit, the city has argued that Mays stole the Jeep. Yet the man who reported his Jeep was stolen that night told police that one of his attackers had an East African accent, which neither of the two boys had.

Oshan, Antonio Mays Sr.’s attorney, also claims that Cruise, the lead homicide detective on the case, said there was no evidence to suggest Mays was committing a crime. The Seattle Times cannot independently verify this because Cruise’s deposition, in which he was questioned by Oshan, is under seal. The city claims the entirety of the deposition should remain under seal because it concerns an open homicide investigation — a move The Seattle Times is protesting in court.

The Police Department has repeatedly declined requests to make Cruise available for an interview.

Seattle’s attorneys argue that the city bears no legal responsibility for Mays’ death because the teenager was allegedly committing a felony before he was killed. Some have criticized this so-called “felony bar” defense because they say it’s been used to shield Washington police departments from scrutiny of lethal force. State lawmakers passed legislation in 2021 requiring defendants to prove accusations of a felony “beyond a reasonable doubt” in order to invoke the statute, which the city would still need to prove.

3. Controversial witness

Survivor Robert West’s testimony is contested.

West, who was also in the Jeep, survived the shooting with a brain injury, memory loss and a seizure disorder, according to his attorney, medical records and his own testimony. He has told medical staff and attorneys different versions of what happened that night.

In West’s own lawsuit against the city — filed by the same attorney in the Mays case — he said he was not driving the Jeep and did not steal the vehicle. Yet the city has also furnished new records showing that after he was admitted to a Kansas City neurological rehabilitation facility in 2023, West said he stole the vehicle with a friend who was shot and died in his arms.

West and Oshan withdrew their lawsuit in August, just as the city made some of these new records available. West has never been charged with stealing the Jeep.

As of this month, Seattle city attorneys and Oshan are locked in a contentious battle over West’s September deposition and a declaration he filed in the Mays suit after his own lawsuit was dropped. In these pieces of testimony, West said the boys did not steal the Jeep and that it was a “CHOP security pass-around car.”

The city has argued that West may not be competent to testify about what happened on June 29, 2020, given his memory loss and the extent of his injuries. City attorneys have pointed to the deposition of West during which Oshan frequently objected to the city’s questions and West suffered a seizure. In it, city attorneys accused Oshan of coaching West.

Oshan has filed a declaration from a neurosurgeon who said West is competent to testify about his version of events.

4. Contaminated scene

Police watched people tamper with evidence at the crime scene but did not intervene.

Seattle police have never arrested a suspect in Mays’ death but say the case remains open and active. They have, since the hours after the killing and up through this year, repeatedly said their investigation was complicated by witnesses tampering with evidence. After the killing, police said detectives were not able to get to the crime scene until 7:45 a.m., nearly five hours after the shooting.

However, a video filed in the civil case shows that police had an opportunity to intervene while people were disturbing the crime scene. Shortly after the shooting, at least nine patrol cars gathered a couple of blocks from CHOP. Police body-worn video from the aftermath of the shooting shows a contingent of police officers approach the crime scene and one of the officers uses binoculars to watch people rifle through the Jeep.

Rather than secure the crime scene as they watch people interfere with potential evidence, the officers are instructed by their incident commander to leave it alone until morning, according to the video.

At one point in the video, someone approaches the officers from CHOP with his hands up and offers to help the police.

“You got anything for us?” an officer asks him.

“Yeah, we’re just trying to see if you guys were trying to come in and help or what we gotta do next,” the man says.

“Leave the car alone,” an officer replies. “Quit digging around in it.”

The officer says that once the sun comes up, homicide detectives will reach out to people at CHOP.

“Let them know this,” the officer tells the person from CHOP. “That we will eventually have control of that vehicle, and when we do it’ll be comprehensively fingerprinted. I don’t think any of these people want their fingerprints inside the vehicle.”

Moments later, the officers turn around and leave. Police declined to answer a question from reporters this month about why they chose to do so.

The lawsuit, originally filed in 2023, is scheduled to go to trial next week, more than five years after Mays’ death. It would represent the fullest public airing of details surrounding the still unsolved killing. But a settlement or dismissal — which would cancel the trial — remains possible.

This story was published in collaboration with The Seattle Times.