Novel virus could spread rapidly among orcas

Some Northwest residents don’t do social distancing well, which leaves them vulnerable to an outbreak of a highly contagious respiratory virus.

These residents are orcas.

The virus is called cetacean morbillivirus.

That respiratory pathogen, closely related to the morbilliviruses that cause measles and canine distemper, has killed thousands of dolphins on the East Coast but has not been spotted in the Northwest yet.

“These morbillivurses, they tend to be pretty nasty bugs,” orca researcher and University of California Davis wildlife veterinarian Joe Gaydos said.

Sponsored

The cetacean morbillivirus has been found in California waters and is known to jump from marine mammal to marine mammal.

“Just like SARS-CoV-2 jumping from bats to humans,” Gaydos said.

SARS-CoV-2 is the virus behind the world’s Covid-19 pandemic.

The southern resident killer whales spend much of their time in Washington waters, but the endangered orcas also range as far south as California’s Monterey Bay.

“It has such a high potential to spread in the population and cause mortality,” biologist Michael Weiss with San Juan Island's Center for Whale Research said of the morbillivirus. “So it's something we're quite worried about.”

Sponsored

Killer whales are very social animals. They often swim and surface so close together that one orca inhales air another orca has just spewed out its blowhole: a recipe for spreading respiratory disease.

“There's a lot of opportunities for this virus to go from one whale to another,” Weiss said.

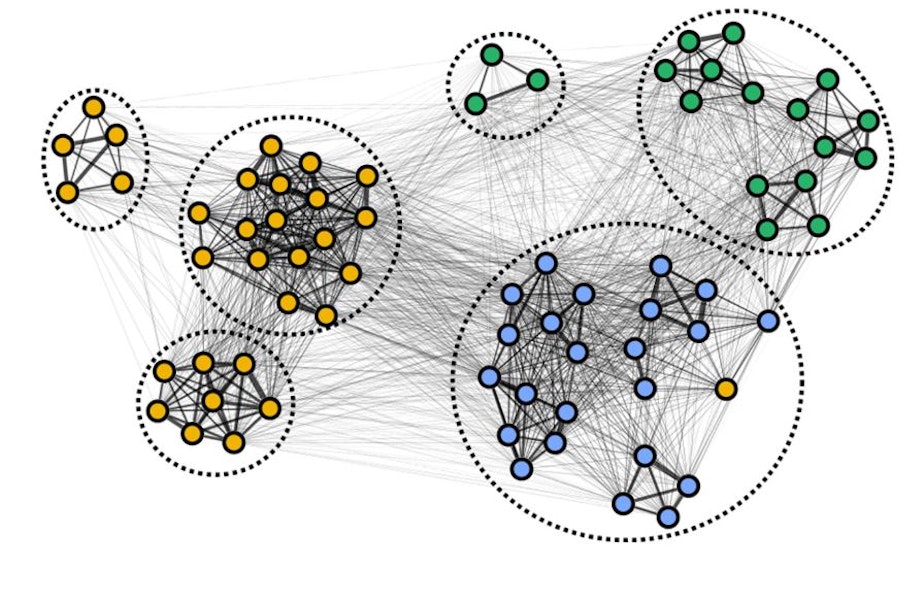

Like humans, orcas socialize with some of their peers much more than with others. The 73 remaining southern resident orcas swim in three large pods (J, K and L) and several smaller groups composed of a female and all her descendants.

Sponsored

With the orcas’ social lives clustered around six small groups, biologists at the Center for Whale Research and England's University of Exeter and University of York wanted to find out whether that social structure might “trap” a highly infectious disease like the morbillivirus before it could sicken the entire population.

No such luck, the researchers found.

They looked at five years of photos of surfacing orcas to reconstruct the southern residents’ social networks, then ran models to simulate how a respiratory disease would spread among them.

The most likely outcome: 90 percent of the population became infected.

“The social structure of this population offers only limited protection from disease outbreaks,” Weiss and his coauthors conclude in a study in the journal Biological Conservation.

Sponsored

Though the orcas mostly socialized within their six social clusters, those clusters had enough contact between them to let the disease spread throughout the population.

The pattern echoes epidemiologists’ warnings that even small amounts of contact between human households, like the occasional social visit or play date, can undo the benefits of social distancing at squelching the spread of Covid-19.

Researchers in Hawaii are developing a morbillivirus vaccine program to protect endangered monk seals, and vaccines are routinely used to prevent the measles and canine distemper morbilliviruses.

But vaccines are unlikely to benefit orcas.

It’s much easier to dart a seal sleeping on a Hawaiian beach than an orca that emerges partially from the sea for a few seconds at a time.

Sponsored

In addition, given the southern residents’ dense social networks, more than half the population would have to be vaccinated to control a morbillivirus outbreak, the researchers found.

“Safely vaccinating 50 free-ranging killer whales is most likely an unrealistic management goal,” Weiss and coauthors write.

The researchers said the best way to help orcas weather the threat of a morbillivirus outbreak is to help them with the threats they already endure: pollution, noise and, above all, hunger.

“The only way to do that is to conserve wild Chinook salmon stocks: through habitat restoration, looking at new fisheries regulations and preserving the fish that they feed on, the forage fish,” Weiss said.

For now, much of that fieldwork has ground to a halt as biologists have had to work from home to avoid spreading coronavirus through their human social networks.

Correction 9:55 a.m., 5/29/20: An earlier version misidentified the University of Exeter.