Part 1: The Empire Builders

Meet the Easterdays – ranching royalty rooted in the Columbia Basin in southeast Washington state. But behind the well-known family name hides a dark secret, concealed in spreadsheets and bum invoices, that’s eating away at their vast empire.

It started as an American success story. The Easterday family took a couple hundred acres of farmland in southeast Washington and grew it into a farming and ranching empire worth millions. Then, it all came crashing down.

Ghost Herd tells the story of Cody Easterday, the man at the center of one of the largest cattle swindles in U.S. history. Easterday invented a “ghost herd” of 265,000 cattle that only existed on paper, and swindled companies including an agriculture giant to the tune of $244 million dollars. Correspondent Anna King has spent two years following the fallout of the crime and its impact on a tight-knit rural community.

Ghost Herd is a story of family and fraud, but also a story about the value of dirt and the shifting powers in the American West.

Search for Ghost Herd in your podcast app.

Ghost Herd is a joint production of KUOW Puget Sound Public Radio and Northwest Public Broadcasting, both members of the NPR Network.

Sponsored

Episode 1: The Empire Builders

Transcript:

911 Tape: State patrol 9 1 1. What's the location of your emergency?

Anna King (narration): December 10th, 2020.

Sponsored

Uh, highway I-82 milepost 13 mile post 13. Okay.

At 3:30 p.m., in Pasco, Washington, a driver reports a major accident on the interstate.

911 Tape: Uh, I, I looked up and I saw the semi truck coming into the westbound lane.

Anna King (narration): The eastbound semi was hauling a trailer full of potatoes, a common load here in a region where agriculture is king.

911 Tape: sounds like it was a wrong way. Truck and, semi

Sponsored

Anna King (narration): The driver of the pickup truck had gone the wrong way up an off ramp. The semi tried to swerve out of the way but couldn't, and slammed it head-on. The 79-year-old driver of the pick-up didn't survive.

The tragedy of what happened that Thursday afternoon was all the more attention grabbing because of the man behind the wheel. A local legend. Gale Easterday.

Gale was the patriarch of a farming and ranching empire that sprawled across a vast basin by the Columbia River in southeast Washington state. Their operation was huge. If you're a meat eater in the U.S. -- and even as far as Japan -- chances are good you've bitten into their beef. The Easterdays owned ranches … feedlots ... vegetable farms … processing plants ... restaurants ... even a private plane.

And Gale's death was the first public crack in the Easterday family facade. In the next few months, the family would appear in headlines again.

Here in this corner of southeast Washington state, deals are sealed with firm handshakes ... and the power of your family's reputation. The Easterday's reputation was ironclad in this community. Which is why everyone was shocked by what came to light after that deadly crash on the interstate.

Sponsored

Cody Easterday — Gale's youngest son, had been using the trust built off of his family's good name to steal. A bigtime lie. He cheated Tyson Fresh Meats, and another big company, out of 244 million dollars. It was one of the largest cattle swindles in the history of the United States.

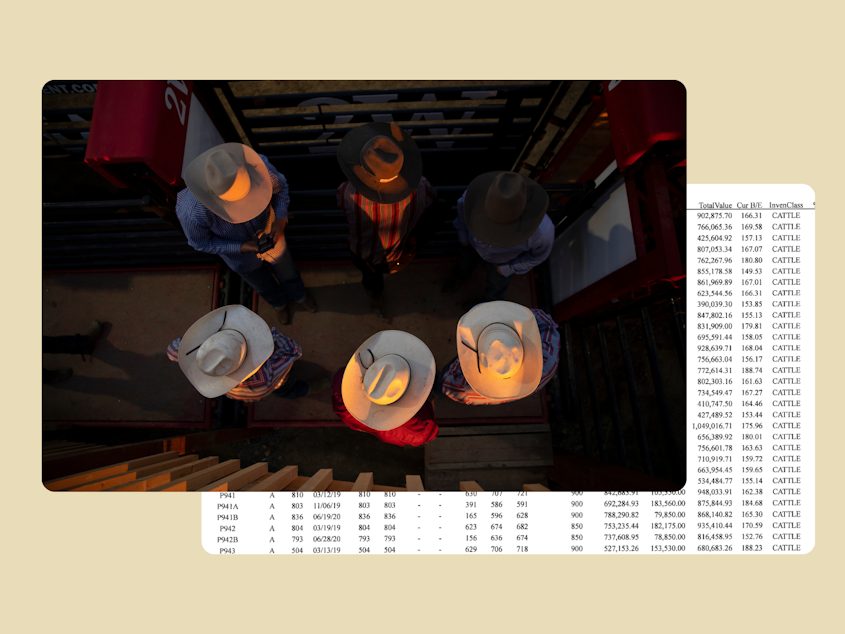

And Cody did it by inventing cattle. He made up fake invoices and billed expenses for a herd of hundreds of thousands of animals that only existed on paper ... Just numbers on a spreadsheet. And this crime was made possible in part by the complexity and scale of our modern ag system.

Cody's audacious lie was a fiction that was fed, gained weight and grew bigger over time. And when it toppled, all that his family had built over four generations fell with it, changing a farming community forever.

From KUOW in Seattle and Northwest Public Broadcasting, This is Ghost Herd … a story about a modern day cattle rustling, a family dynasty and the myths we tell ourselves about the West. I’m Anna King.

Rodeo Announcer: Welcome the Basin City freedom rodeo, 2022 and I got one question for each, everyone you folks out there this evening.

Sponsored

Are you ready?

Anna King (narration): Basin City's population is a little over 1,000. It's plunked right in southeast Washington state. It's in Franklin County which produces more than half-a-billion-dollars worth of hay, corn, potatoes and other ag products. It's all part of the heavily-farmed heart of what's called the Columbia Basin.

This is the kind of place where workers grab tacos for a quick lunch. There's also lots of steeples here -- a Lutheran church, a spanish parish and a LDS chapel. Basin City's tire shop carries big tractor tires. And the Columbia River rolls south, just outta town.

Rodeo Announcer: [national anthem Sound] Rodeo fans, let me hear you. I wanna know one thing,

Basin city, is this a cowboy town?

Anna King (narration): Basin City is a "cowboy town." And as the popular Brooks & Dunn song goes, people wear their ... "boots to dinner, drive [their] trucks to church."

We're at Basin City's annual summer rodeo ... About 25-hundred people drive in from all over for it each night.

And Basin City is the hometown seat of the Easterday family empire.

The Easterdays help put on this rodeo. Five of them sit on the committee. And Gale's grandson -- Cody's son -- even won the wild-cow milking contest.

Rodeo Announcer: Cutter Easterday!!!!!

Anna King (narration): Here, in the fertile Columbia Basin -- with orchards, grapes and massive fields of crops -- is where the Easterday family built their farming and ranching empire.

Gale Easterday's father, Ervin, moved the family here in 1958. Gale would have been about 17 years old. The family moved here from Nampa, Idaho to 300 acres of undeveloped land.

Early on, Gale took right to farming, partly out of necessity, but partly for the love of the land. The farm's company website says that a young Gale spent hours on a Caterpillar leveling and clearing this sagebrush in those early days.

Gale Easterday: They were always saying how farming was so hard. Farming was never hard to me.

Anna King (narration): That's Gale Easterday from a video posted on Easterday Farm's Facebook page. He said farming was never hard for him.

As Gale got older, he kept up the family operation and married a young woman named Karen.

Ben Casper: Gale and Karen were workers.

Anna King (narration): This is Ben Casper. Ben was Gale's tire guy. Tires mean the world to a farming operation. Tractor tires don't usually wear out in this country, they weather out -- the sun and the rain and the cold beats on them. Ben owned that tire shop in Basin City and would often go up to the Easterday property to deliver tires or propane.

Ben Casper: And I'm telling you what, Karen was out there in her rubber boots and doctoring and feeding and taking care of a big, you don't call 'em a herd, but a bunch of pigs all the time, they had a big operation there.

Anna King (narration): Ben says Gale had a reputation for loyalty to the people he knew. And not taking any B.S.

To see that in action, you don't have to look farther than his spinnin' tractor tires.

Ben tells me about a time the manager of a tire store in the Tri-Cities tried to take over the Easterday account, saying that the Easterday property was closer to his store.

Ben Casper: And I knew that was not a good idea because I knew Gale and I said, I don't think you should do that.

That's not a good idea. He said, no, it'll be fine. He said, we'll, we'll just transfer it and we'll take it over. No problem.

Anna King (narration): A few days later Ben's phone rang. It was Gale.

Ben Casper: And I'm not gonna say everything he said, but it was essentially this: Ben, the last time I checked, this was still the United States of America. And I have the right, actually it was the blankety blank, right. To do whatever the blankety blank I wanna do. And if I wanna buy tires from somebody I'm gonna do it. And I don't want somebody else coming on my place. Do you get that? And I, he was, he acted like he was really mad at me when he was saying, I want to keep the business with you.

Anna King (narration): After he hung up, Ben thought ...

You know, Gale really is a loyal guy, but he's not gonna have anybody tell him what to do.

Anna King (narration): You need that determination and grit to be a success in farming. Because in farming you can do everything right and still fail.

The best farmers tell me that they are just two bad years from losing it all. It just takes a market change, shipping problems, COVID, a long spell of drought or too much heat for it all to tumble. Much of it is out of the growers' hands.

And in 1987 Gale and Karen had a bad year. So bad, they went bankrupt.

Gale made it clear in that Facebook video, that keeping the family in the farming business is what mattered to him.

Gale Easterday: my family's done a big part of it. We lay it all on the line.. That's the only thing making it work. Family. There's no other reason to build it.

Anna King (narration): Family, there ain't no other reason to build it.

It's hard to know the impact of the bankruptcy on the family farm, but two years later in 1989, Gale's teenage son Cody decides not to finish college so he can help his family farm. To help them build back from bankruptcy.

Ben Casper: Things really changed for Gale when Cody came along

Anna King (narration): Cody has been descibed as eager, driven, and a take-no-prisoners and get-all-you-can personality. He was forged in the Columbia Basin. A young man poised to take over the farming operation. He was ready to grow.

Cody's sister says that her brother always wanted to farm even from very young. She describes how he would play with his mini tractors when he was a lil' scraper -- about three years old. He would plow little fields in his mother's garden.

He had family land to start out with. And ambition.

From all accounts, Cody is a shrewd businessman. Ben Casper, the tire shop guy, watched as Cody took over more control of the Easterday operation. He says that Cody was just really aggressive with expanding the farm.

Ben Casper: I think there was no fear in him and he just went for the Gusto and he understood everything. He knew just what had to happen. And he did it.

Anna King (narration): Cody was rarin' to farm. Youth are optimistic, he made it happen.

By the age of 20, he was "responsible for overseeing all financial matters for the family business."

The Easterday family website says that once Cody became a partner ... the Easterday farm became a father-son enterprise once again.

Around this same time, Cody met a young woman named Debby.

Debby says the two met at the county fair the summer before her senior year of high school. When Cody asked her out on a date a few weeks later. He hinted they would go see a movie. But on that night, Cody instead drove her to a parcel of farmland that he'd recently purchased.

It was at night, Debby describes seeing rows of lights off in the distance. Cody explained those were the lights on irrigation pivots, watering crops. Twenty-three in total.

Debby says that she didn't quite understand his excitement or why he thought this was a good idea for the first date, but his enthusiasm was contagious and intriguing.

Cody was beginning to build his empire.

As other farmers in the Basin sold their land, the Easterdays bought it up. The land they couldn't buy, they rented. The more land they got, the more they could leverage that, to get even more land.

The Easterdays also bought machinery so they could cut all their own crops. They hired on more people, they bought a potato and onion processing facility so they could own more of the supply chain -- and put Cody's sister in charge of running it.

The entire Easterday family has a strong chain of business that interlink. Restaurants, forage companies, construction companies, the produce processing. Together the family built an empire that corralled millions of dollars each year.

The Easterdays owned large homes across the Columbia Basin, and in Arizona. The family owned a $600,000-dollar private plane, hired pro-pilots and even had an expensive camper they'd take to Washington State University football games to tailgate.

So, the Easterdays kept buying up property, growing crops, filling in the patches of their quilt. Their farm that started on 300 acres of sage-covered land -- they grew that into an empire of corn, onions, potatoes and wheat that spanned tens of thousands of acres over three states.

Ben Casper: Everybody who watched Easterdays grow, uh, knows that it's Cody cuz Gale farmed, but he, he didn't, you know, go like crazy. When Cody came in there, he's the one that made it happen. And, uh, he, uh, yeah, he's, he's a very talented individual.

Anna King (narration): Cody grew the business in a startling way. From 1 million dollars in revenue when he began. To $250 million dollars ... in just 20 years. From 7 employees to nearly 200.

But the empire is not all Cody Easterday's doing. To understand the Easterday empire -- we first need to understand the landscape it's built on -- a unique combo of geology and taken land. The foundation of his wealth and power. And it's the foundation of what comes next.

We'll plow into it after the break.

BREAK

Anna King (narration): If you look at the area around Basin City on Google Maps, it looks like a patchwork quilt. It has green squares and circles and odd shapes all stitched together with roads tracking North-South and East-West. This is Easterday turf. Sand and desert fills in the rest.

It's this dirt that makes this land so valuable. This soil provides the medium for the Easterdays to grow their corn and potaotes, their onions and hay. But it wasn't always this way...

Chep Gauntt: The basin was hostile as it was being developed.

Anna King (narration): This is Chep Gauntt. He's another farmer in the Basin whose family has a similar origin story to the Easterdays.

Chep Gauntt: This was a very, very difficult area to start in. It's, it's hard to describe how tough conditions were as you take fields outta sagebrush.

Anna King (narration): Taking a field out of sage means yanking up the old-brush with a tractor and hand tools. Removing rocks, and bunch grass. Plowing it under. This is how you turn beautiful desert into fertile farmland.

Thousands of years ago, Ice Age megafloods washed down from what's now Montana, bringing in massive amounts of sand and silt. All that sediment in the water was left behind here in the basin. That's why there's ag here at all. It's an ancient conversation between fire, giant floods and wind.

But these early farmers, like the Easterdays, needed water to pour on that desert soil. And the mighty Columbia River runs right through the Basin. To tap that, the government built an engineering marvel. The Grand Coulee Dam.

Archive Tape: soon water will flow along the pipes into the waiting conduits, bringing life to a million dead acres.

Anna King (narration): This concrete behemoth would become the largest hydroelectric producer in the United States. The water it redirects now feeds more than 670-thousand acres in eastern Washington.

Water is fed through massive man-made canals -- concrete rivers really -- and then ever-smaller canals. It's like the large veins that lead to capillarys that feed this body of farmland.

Around the same time all this irrigation land was being created, scores of WWII vets freshly home from the frontlines were looking for work. The federal government saw an opportunity in the Basin.

Archive Tape: President Truman drives to the Grand Coulee dam for the dedication ceremonies, mr. Truman says the grand Cooley project is the reason the Northwest is America's fastest growing section.

Anna King (narration): WWII vets were given the first crack at owning pieces of this new farmland, and hopes of attaining an idylic middle class lifestyle.

But it wasn't easy. The early farmers in the Columbia Basin had the difficult task to "break the land out of sage." When Basin farmer Chep was a young kid in school, he didn't know that people actually got to go on vacations during spring break.

Chep Gauntt: Spring break was like a different name for rock picking. They were the same name. Spring break just meant that you got to pick rocks all week. It didn't, you didn't get to pick 'em just after school. You got to pick all week. Spring break was when the crops were starting to come up. A lot of blooming, a lot of growing of the, of everything. And, and so you got outta school and you went home and you did whatever work the farm needed.

Anna King (narration): Chep says many of the early farmers slept in Army surplus tents. They didn't have actual homes and lived without indoor plumbing for years. But the promise of owning a bit of that dirt kept them working hard.

Chep Gauntt: It was just a bleak place to be and all that sand and how these world war II vets scrapped their way through that is unbelievable.

Anna King (narration): It may be unbelievable, but that only increases Chep's appreciation for the land. Now, the Basin feeds much of the world.

He steps out into a stand of timothy on his farm. Timothy's a forage crop for horses and dairy cattle. It looks like perfect, waist-tall summer grass with bobbing heads of purple.

Chep Gauntt: But I was thinking a while ago, you know, America, the beautiful, you know, you can see the spacious skies. This is not Amber, but it's green waves that you see that, you know, this, this farming and out here, it fits America, the beautiful. Oh, beautiful for spacious skies for amber waves of grain for purple mountains.

Well, we can't see the blues from here, but you know, it's, we're just down the hole. We can see 'em from up on the hill, but it's, it's got all those, what a better place in the world to be than right here. This is it.

Anna King (narration): But this beautiful land had value long before ditch irrigation and row crops. And just about everyone here -- including me -- has benefited from land taken from tribes. This is not a secret, but that doesn't mean it's openly talked about.

Bobbie Connor: I want young people who grow up here to comprehend that this is still our home. When you live in the Tri-Cities, it's still our home. When you live in Walla Walla, it's still our home. When you live in LA Grande or Hermiston or Milton Freewater, it's still our home when you live at Arlington. We've never abandoned our relationship with the vast Homeland.

Anna King (narration): This is Bobbie Conner. Bobbie's home is on the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Reservation in northeastern Oregon. Her traditional homeland contains the land where the Easterday family farms and benefits from this changed landscape.

The idea that the native population of the Basin didn't own the lands is an old myth. It was an easy way for settlers to justify taking it from them. Bobbie's people were forced onto a reservation and most of their homeland was wrested away from the Cayuse, Umatilla and Walla Walla. Many were sent to live with other tribes -- the Nez Perce, or the Yakama. But eventually in June of 1855, the leaders of the Umatilla tribes secured a promise for a small reservation, only a fraction of the lands the tribes used to run -- some 6.5 million acres, nearly as much land as the entire state of Maryland.

Bobbie Connor: And the consequence is, is that we live in a tiny subset of our homeland and yet our brains and our hearts don't embrace the tininess as our homeland. We still have the expectation that this vast landscape is still our home.

Anna King (narration): Her concept of home doesn't end at the line on the reservation map. The tribes and bands of the region would often travel multiple trails over the long period from early spring to late fall -- a "seasonal round." She says they left tools on the landscape -- like mortars, pestles, grinding stones, clubs. Things made of basalt that you wouldn't carry in your saddle bags from camp to camp.

Bobbie Connor: We left them on the landscape where they belonged, where their utility occurred, and we would come back to that place each year and expect to find them there: crossing stones, marking stones for places, um, stories in the rocks. Those all had a home.

Anna King (narration): No fences or bank notes needed to mark out individual ownership of space. But indigenous people owned this land.

The seasonal round would take them along rivers, into the mountains, into the plains and back to the lowland winter grounds -- some 1,000 miles each year.

Bobbie's great aunt and grandmother traveled those seasonal trails into the 1900s. Bobbie tells me her great aunt traveled these routes on horseback as a child.

Bobbie Connor: south towards granite and Sumpter in Ukiah over to Catherine Creek, over into the Minam, um, down over to the Snake river, down the Snake, back up around the Snake all the way, um, to the Tri-Cities and home again.

And she knew the land in a different way

Anna King (narration): Bobbie saw that in the way her grandparents lived too. She remembers as a child sitting in the back of her grandpa's light-yellow 1960s four-door Chevrolet ...

Bobbie Connor: traveling along the Grande Ronde river when I was young, I don't know. I don't recall precisely how old I was, but grandma started singing a song, an Indian song, a tribal song. And when she got done, she kind of giggled and looked at grandpa and said, I couldn't remember that song.

I thought I'd lost it, but I must have left it here

Anna King (narration): Bobbie tells me it wasn't clear to her until much later what her grandmother meant by that.

Bobbie Connor: for her, she had left that song along the trail and she had found it along the trail. And it had been kept in a safe place until she found it again.

Anna King (narration): The land was holding that song.

Pushing and fighting Native Americans off of the majority of their land, meant settlers and later, farmers could claim their spot. Grow their power and wealth.

Cody Easterday has benefited having control of major swaths of Columbia Basin land. But Cody really grew when he leaned into his beef-raising industry.

He used his family's good reputation, as a young man to partner with Tyson Fresh Meats.

Tyson wanted to grow it's Wallula plant operation in the Columbia Basin. And Tyson trusted Cody's good reputation to take on the job.

And Cody for his part, double-pattied down on the cattle business.

In a letter to a federal judge, his wife says when he took on this new industry -- a cattle feeding business-- it was a tremendous amount of work, and he was succeeding.

Cody grew his operation to as many as 65,000 cattle on two feedlots.

When asked how Cody does it, his wife would reply, "I don't know, I just know he loves it."

Cody tracked down national experts to help him understand cattle habits and how to care for them. Vets, and even nutritionists from the Midwest to help inform his opertation. One such nutritionist would fly in monthly from Missouri to check Cody's cattle.

Cody was raising most all his beef for international foods-giant Tyson Fresh Meats. His animals made up two percent of their total beef operation. His likeness was even plastered on packages of beef sold in Japan under the brand "Cody's Beef."

All this success stemmed from his family's great reputation. He was a handshake deal guy. The appearance of an honest dealer.

Darryl Olsen: He always struck me as a very solid individual. You know, he was not misleading. He was not arrogant. Um, you know, very trustworthy relate in any kind of the dealing I'd ever had.

Ben Casper: Cody is probably a genius in some ways.

Stacy Kniveton: I've always been able to walk right up and say hi and smile and a handshake.

Olivia Grassl: Community supporters

Anna King (narration): But his bullish nature on business -- and a dark secret -- are about to get him into trouble. Soon Cody -- and his empire -- are gonna fall. He's orchestrated one of the largest cattle rustling schemes in the United States. Two-hundred and sixty-five thousand cattle that don't exist. A 244-million-dollar scam.

Cody's on the very edge.

Alan Schreiber: Cody was a bit of a, you know, Icarus that, you know, flew too close to the sun.

Anna King (narration): Federal prosecutors are circlin'. Cody's facing up to 20 years in prison.

Jump in the pickup. I'm gonna show you around the Columbia Basin. This is my turf. I've reported for nearly 15 years out here. I've been steeped in alfafa, spuds and cattle. I'll tell you a story of rural America. We'll dig into the value of dirt. And one family's powerful empire.

Eric Reubel: It's a great American success story. That ends crippled by greed

Anna King (narration): This is Ghost Herd. I'm Anna King.

Credits

Anna narrator: Ghost Herd is a joint production of KUOW Puget Sound Public Radio and Northwest Public Broadcasting, both members of the NPR Network, a coalition of public media podcast makers. To support our work, contribute to KUOW, NWPB or your local NPR station … and tell a friend or two about this podcast. It helps.

Ghost Herd is produced by Matt Martin, and me, Anna King. Whitney Henry-Lester is our project manager.

Jim Gates is our editor.

Fact Checking by Lauren Vespoli Cultural edit by Jiselle Halfmoon

Our logo artwork is designed by Heather Willoughby.

Original music written and performed by James Dean Kindle

Recorded by Addison Schulberg With additional musicians Roger Conley, Andy Steel and Adam Lange I'm your host Anna King.

If you have thoughts or questions about Ghost Herd, we’re listening. Get in touch at KUOW.org/feedback.

Correction, 4:25 p.m., 2/27/2023: An earlier version of this story misstated when the Ice Age megafloods occurred. Most of the Missoula floods happened between 15,000 to 20,000 years ago, and some may have occurred as long as a million years ago.