Seattle pays $1.9M to woman who says police officer raped her as a minor, decades ago

The city of Seattle has paid nearly $2 million to settle a lawsuit that alleges an officer working for the Seattle Police Department in the 1970s raped an underage sex worker during that period.

Two women who were forced into sex work decades ago built different lives for themselves in the intervening decades. They have retained the connection, friendship and support they developed all those years ago.

C

andace Sparks wears a T-shirt that says “Stand In Your Truth.” It’s what she says she was doing when she filed a civil suit against the City of Seattle and former Seattle Police officer KC Smith, Jr, back in December 2021.

These days, Sparks is a deputy King County Court clerk. But decades ago, as a teenager, she was living in a girl’s home in north Seattle.

“The pay phone rang, and that was the beginning of my story,” Sparks said in an interview with KUOW.

Sponsored

That call set off a series of events that would lead to a traumatic period in Sparks’ life.

According to an interview with The Seattle Times from 2022, the same man continued to call and eventually persuaded Sparks to run away.

The man on the phone turned out to be a pimp.

He forced Sparks into prostitution in downtown Seattle when she was 15 or 16 years old.

Court documents state that one night during this time, a man solicited Sparks’ sexual services, posing as a customer.

Sponsored

“Before engaging in any sexual acts, the man revealed himself as a Seattle Police Department officer, and threatened to arrest Ms. Sparks and send her to a juvenile detention facility,” court documents say.

She was not arrested that night.

But later, the same officer approached Sparks in a Seattle Police van and told her to get in.

Court documents say the man and his partner drove Sparks to the Seattle waterfront where she was forcibly raped and pushed naked out of the van after the attack, her clothes thrown onto the street beside her.

Like so many sex workers who experience trauma or abuse, Sparks didn’t report the incident. But she said she told her pimp that she wanted out.

Sponsored

Sparks said her pimp and his friends drove her to eastern Washington, out in the woods. There she said she witnessed them brutally beating another woman.

“I don’t even know if she lived. And [he] asked me, ‘Who are you more afraid of, the cops or this?’”

Eventually, at around 18, Sparks was able to leave prostitution. She got a job at a restaurant.

It all comes flooding back

It was while working at the restaurant that Sparks met a woman who had been through a similar experience.

Sponsored

KUOW is not naming this second woman to protect her privacy.

The woman had also been trafficked into prostitution and worked the streets around the same period as Sparks.

The two became friends. They stayed in touch.

Then in 2019, a child Sparks' friend had placed for adoption started looking for her biological father.

The friend didn’t want to know the results of the search, but her child contacted her when she got a hit on an ancestry DNA site which indicated her father was likely former SPD offer, KC Smith, Jr.

Sponsored

According to court documents, a subsequent DNA test confirmed the paternity.

The news was a shock. But the woman had memories of a man who, in the early 1980s, solicited her for sex.

Afterward, she said the man pulled out his Seattle Police badge and gun, took back his money and threatened her.

Roughly nine months later, she had a baby girl who was then adopted.

When Sparks got the call from her friend telling her the news, Sparks recognized the name of the officer. She told The Seattle Times last year that it was like fireworks going off inside her head.

Court documents show Sparks identified Smith as the officer who allegedly raped her. All these years later, she said the harm still lingers.

“He said, ‘You're a worthless piece of crap. Nobody will ever believe you.’ And I carried that through my whole life,” Sparks said.

“If I fail at anything now, that man's voice is still in my brain,” she said.

Smith continues to deny in full the claims of rape and assault made by both women. He told the Seattle Times last year that the lawsuit against him was “ridiculous”.

An investigation by the city’s Office of Police Accountability could not substantiate Sparks’ claims and ruled the probe into the allegations inconclusive. But the report states that the office found her story to be credible.

The settlement

The outcome represents a rare case in a legal system where abuse against sex workers often goes unheard, and even more often leaves plaintiffs without any positive outcomes.

Unlike a trial, a settlement gives neither an innocent nor guilty verdict in the case.

However, in civil suits they are very common, according to Brooke Coleman, vice Dean for academic affairs and Fredric C. Tausend Professor of Law at Seattle University.

A settlement indicates that the city conducted a risk assessment and decided it wasn’t worth sending the case to trial.

The settlement, reached in May, does not admit liability or wrongdoing on the part of the city or the involved officer, which is the norm for these kinds of legal documents.

As for the amount, $1.9 million, Coleman said that all comes from the city, not the accused former officer.

And while it could be argued that it’s a small amount given the severity of the accusation, she said it’s still significant, especially for an entity without incredibly deep pockets.

“I think that tells us that this case was taken seriously by both sides,” she said.

In a statement, Nick Gross, a lawyer for defendant KC Smith, Jr, said his client had not wanted to settle the case.

“KC is completely innocent. He was looking forward to clearing his name at trial. Unfortunately, the City of Seattle was authorized to settle the claims against him and did so against his will,” Gross said.

In a statement from the City Attorney’s office, a spokesperson said the city paid the settlement amount in exchange for a release of all claims against the city and Smith.

“The City admitted to no liability in the resolution of this litigation,” the statement said.

For Sparks, it counts as a win.

“I know it's not a guilty verdict,” she said. “But a notice of settlement is just as good in my book.”

Sparks said that had the case gone to trial and received a guilty verdict, it would likely have been appealed, dragging things on for years.

Now, it’s over. And that’s a relief, she said.

Paying it forward

Sparks wanted some of the money to go towards helping people going through the same trauma and difficulties she experienced decades ago.

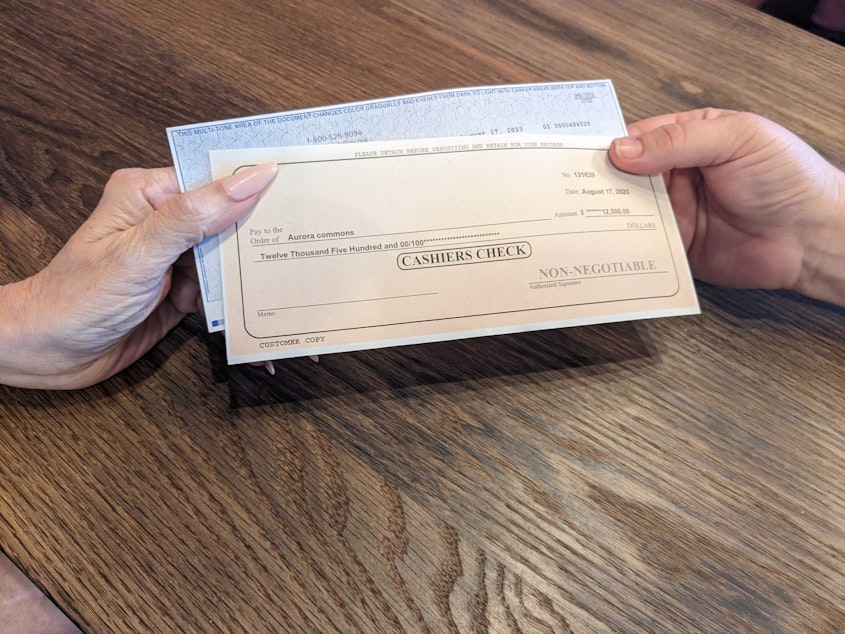

On a hot August day, she walked into the relief provided by air conditioning at the Aurora Commons on Aurora Ave in Seattle, a check tucked securely into Sparks’ bag.

The Commons is a sort of community living room that offers services for people who are experiencing homelessness, and for people who are engaged in sex work along that strip.

It has the vibe of a busy café, colorful feature walls paired with neutral gray furniture and wooden tables.

Here, people can access food, clothes, medical services, case management, respite, and more.

When Sparks and and her friend were working on Seattle streets, resources like this didn’t exist.

“It was unthinkable,” Sparks said. “I didn’t have a doctor for the whole time I was out there, you know. So this, it’s really important.”

Sparks said the Commons feels like a lifeline for people, and she’s thrilled to be able to help support it. The organization received $25,000 from the settlement as a donation, and another $25,000 from the law firm that represented Sparks.

“We feel really honored to be the recipient of that gift,” said Elizabeth Dahl, executive director of the Aurora Commons.

Dahl said the money will go toward things like the organization’s emergency fund for women.

She said the timing is special because three mothers have come to them recently needing support.

“Women who are waiting for other kinds of housing and support, who are wanting help and to exit the life out here on Aurora,” Dahl said. She said these people often have nowhere else to turn.

Sparks’ message to people in those situations is that it’s not easy to take their experience to the courts, but there are people who will listen and help.

Correction: A previous version of this story misstated the amount donated to the Aurora Commons from the settlement.