Senate Votes To Restore Regulations On Climate-Warming Methane Emissions

The U.S. Senate has taken a step toward more vigorously regulating climate-warming methane leaks from the oil and gas industry, a move supporters say is key to achieving President Biden's ambitious climate goals.

Senators reversed a Trump rollback by voting on a resolution under the Congressional Review Act (CRA), which gives them the ability to undo agency rules passed in the last months of the previous administration.

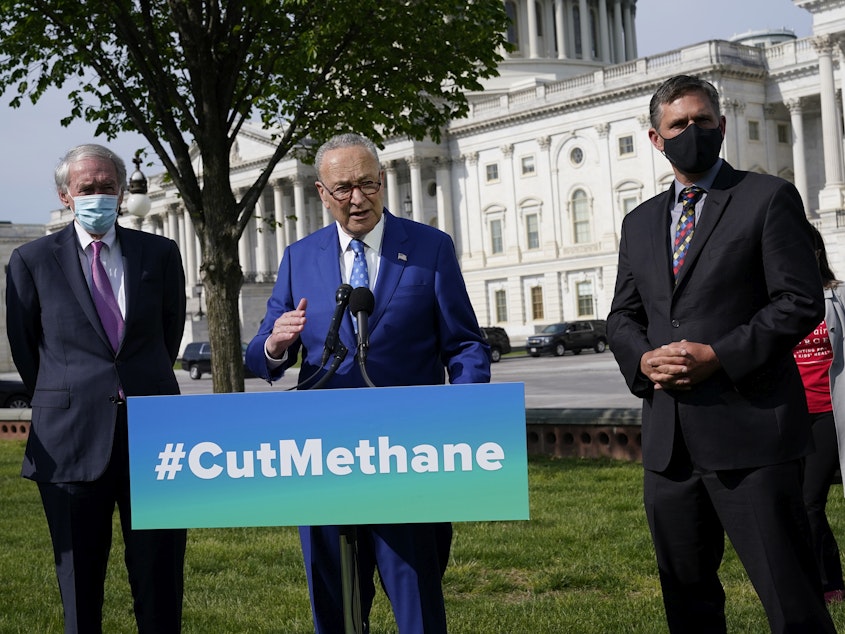

"What we're voting on today is the legislative equivalent of a double negative. This is the repeal of a repeal," said Senator Angus King, I-ME, at a press conference before the vote.

If the House passes a similar measure it would reverse an EPA methane rule finalized last year and leave in place a stricter 2016 EPA rule, finalized during the Obama administration.

Methane is the main ingredient in natural gas. When released before it burns it's a far more potent greenhouse gas than even carbon dioxide. But it does not linger in the atmosphere nearly as long. That means eliminating leaks now could have an immediate effect on global warming.

Sponsored

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said earlier this month that methane and carbon dioxide "continued their unrelenting rise in 2020 despite the economic slowdown caused by the coronavirus pandemic response."

The oil and gas industry is the largest source of human-caused methane emissions. A recent study by Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) found that cutting methane emissions now could slow the rate of global warming by as much as 30 percent.

"It is so harmful to the earth's climate and our ability to meet our greenhouse gas reduction goals, that we simply can't meet those goals unless we address this pollution from oil and gas operations," says Dan Grossman with EDF.

The senate vote was largely along party lines with a few Republican senators, including Senator Susan Collins of Maine, Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina and Senator Rob Portman of Ohio, voting in favor of the resolution.

Senator Martin Heinrich, a Democrat from New Mexico, said in his oil-producing state methane leaks from various points of the production process, including wells and pipelines. "So much so that a few years ago NASA actually could see the methane plume sitting over the northwest portion of my state," Heinrich said at a press conference before the vote.

Sponsored

Speaking against the resolution, Republican Senator Shelley Moore Capito of West Virginia said, "We shouldn't demonize an industry that is part of the lifeblood of our economy." She called the vote a "political stunt" and echoed industry arguments that it's reducing methane emissions even as gas use increases.

But the oil and gas industry is split over this issue. Larger companies generally support the Obama-era rules and smaller companies oppose them.

Big oil is heavily invested in natural gas and worries that if methane emissions aren't controlled, that could undermine arguments that gas is a cleaner-burning fossil fuel than coal.

"We cannot make the climate case for the widespread use of natural gas if we don't manage and contain it," says Shell U.S. President Gretchen Watkins in a statement to NPR. Other large oil companies expressed similar views on Twitter this month, including BP, Equinor and Total.

Smaller drillers worry stricter regulations will be expensive. They prefer voluntary measures to limit methane emissions.

Sponsored

"IPAA supports cost effective methane emissions management under the Clean Air Act, but it believes that specific standards are needed for small businesses and low production wells," says Lee Fuller, executive vice president of Independent Petroleum Producers of America. His group says some wells produce just a few barrels a day and could become unviable with stricter regulations.

The senate vote comes as President Biden has called for dramatically reducing greenhouse gas emissions to address climate change. His climate change plan calls for a carbon-neutral power sector by 2035 and for the broader economy to be carbon-neutral by 2050.

The House is expected to vote on the CRA resolution in coming weeks. [Copyright 2021 NPR]