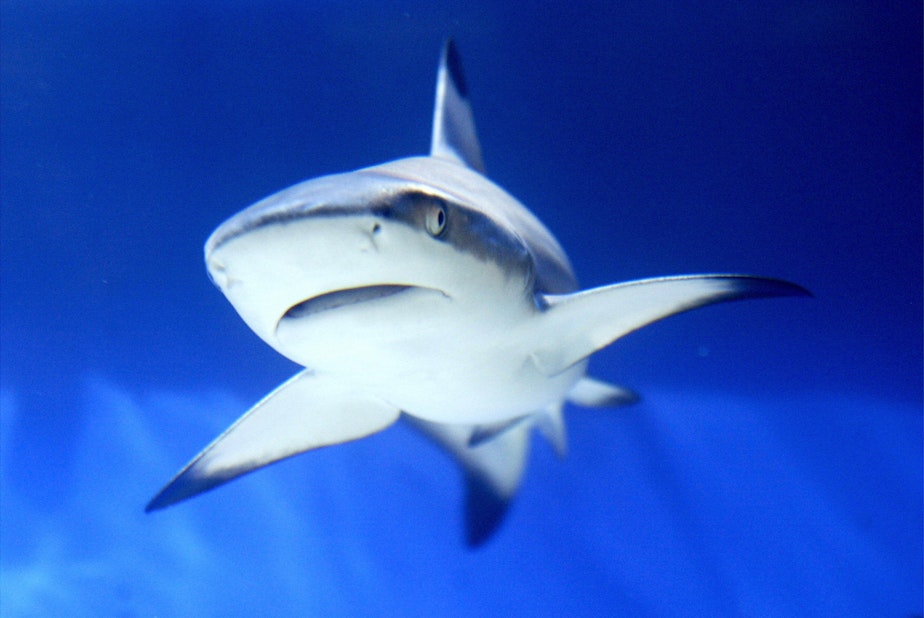

Shark Populations Are Declining Toward 'Point Of No Return,' Scientists Say

The ocean’s top predators are in decline.

A study published by an international team of scientists last week in the journal Nature found the global abundance of oceanic sharks and rays has plunged more than 70% since 1970. In the early 2000s, up to 273 million sharks were killed every year, the study says.

Over the last 50 years, an increase in fishing has coincided with a growing international market for shark meat, fins and the gill plates from species such as manta rays, says Sonja Fordham, a co-author of the study and president of the group Shark Advocates.

“This is a problem we see for a lot of fish species,” she says, “but it often can be much more acute for sharks and rays because they tend to grow very slowly and their populations can be easily depleted and then take a really long time to come back.”

Protections for sharks and rays vary throughout the world. Countries such as the U.S. “comprehensively manage their shark fisheries,” Fordham says, while others have banned shark fishing entirely.

Sponsored

But most countries don’t set limits on the number of sharks and rays caught. International cooperation is important for these wide-ranging, oceanic species that many countries fish, she says.

Some studies are now starting to come out about the impact of climate change on shark populations, she says.

“I would say certainly climate change is going to have some negative implications, but those are coming on the horizon,” she says. “And overfishing is here right now. It’s been here for decades.”

Researchers looked at 31 species of sharks and rays and found that three-quarters of them were threatened with extinction. Losing these species would jeopardize the health of ocean ecosystems because many of them are important predators, she says.

Extinction would also harm food security in developing nations and waste opportunities for sustainable ecotourism around the world, she says.

Sponsored

In China, advocacy groups have made progress on limiting finning to make shark fin soup through regulation and consumer information, Fordham says. Still, demand for shark meat is rising and the creatures are used for many purposes across the world such as sport fishing.

“Every country can do better,” she says.

The public’s negative perceptions of sharks contributed to the decline, with these animals receiving less research and conservation efforts, Fordham says. People are misinformed about the threats sharks pose to humans and other species, perceiving them as pests. And sharks are viewed as less valuable than commonly eaten fish such as tuna or cod.

The report includes some bright spots: White shark and hammerhead shark populations off the U.S. coasts are rebounding, though hammerheads are still globally endangered.

The U.S. banned the retention of white sharks in the 1990s and implemented protections of the species’ marine mammal prey, she says. Now, the population is rebounding on both coasts, and these success stories highlight important lessons in conservation.

Sponsored

“One of the simple lessons is that relatively basic safeguards that aren’t always perfectly implemented can really help save sharks and rays,” she says.

Chris Bentley produced and edited this story for broadcast with Tinku Ray. Allison Hagan adapted it for the web.

This article was originally published on WBUR.org. [Copyright 2021 NPR]