She lost her sister to COVID-19. The death highlights the heightened risk to people with developmental disabilities

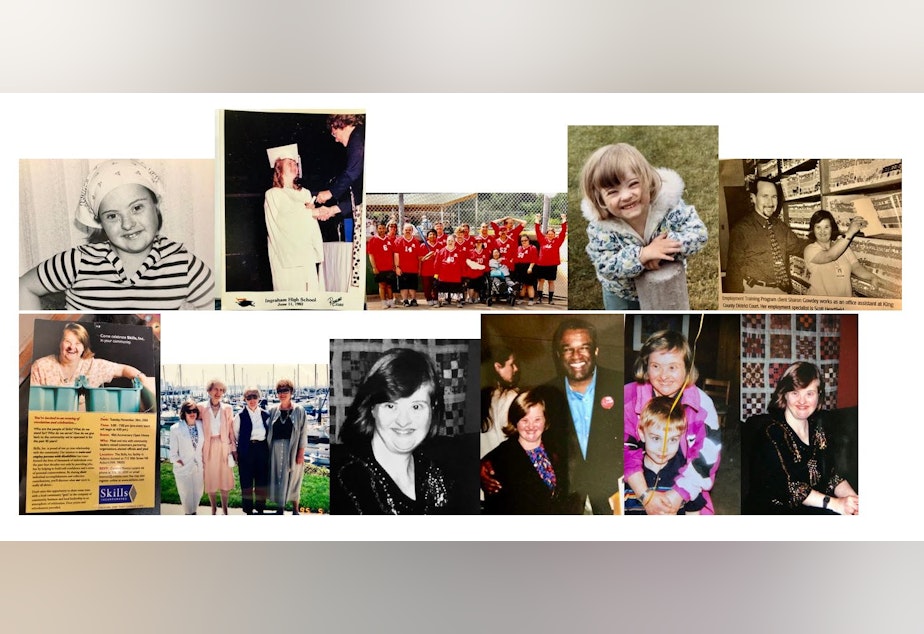

At Christmastime last December, Sharon Gowdey was a healthy 56-year-old woman with Down syndrome. A video from a holiday party shows her in a Santa hat dancing to a Michael Jackson song as strobe lights light up the dance floor.

Four months later, Gowdey was dead of COVID-19.

“When they turned the ventilator off, it was less than five minutes and she passed away,” said her sister Kathleen Hesseltine.

Gowdey’s decline happened suddenly.

“In the morning she was on a minimal amount of oxygen and hours later she’s on a ventilator and can’t breathe,” Hesseltine recalled in an interview.

Sponsored

Gowdey is one of 13 community residential clients of Washington’s Developmental Disabilities Administration (DDA) who’ve died from the virus. That’s a fraction of the more than 1,200 COVID-19 deaths in Washington, but it’s a significant number when put in context.

Early data show a 13.5 percent death rate among people with developmental disabilities who live in state-supported, community-based settings and have tested positive. That’s nearly triple Washington’s current statewide death rate of 4.6 percent. It’s a similar story in other states, including Oregon.

“Obviously it’s concerning for the Developmental Disabilities Administration,” said Shaw Seaman, the chief of quality assurance for Washington’s DDA.

Developmental disabilities is an umbrella term that includes intellectual disabilities and conditions such as cerebral palsy, autism and other neurological conditions. Washington has approximately 35,000 DDA clients. The majority live with their families, but around 4,500 are served in supported living residential settings where often two to four clients live together.

Seaman noted that his agency’s clients are particularly vulnerable to complications from COVID-19 because of underlying conditions, like diabetes. Those who live in group settings face even more risk, especially because caregivers often work in more than one community-based home.

Sponsored

“You’ll have one or two cases that come up in a particular home and it might creep into another house,” Seaman said. “It kind of spreads like that.”

COVID-19 has also spread rapidly through nursing homes and other long-term care facilities. In fact, more than 60 percent of COVID deaths in Washington have been linked to long-term care environments. In addition, the virus has disproportionately affected African Americans and Hispanics.

Sharon Gowdey was a client of Alpha Supported Living Services – a nonprofit founded in 1974 that serves more than 200 developmentally disabled people in 88 homes across King, Snohomish and Spokane Counties.

“We were hit pretty hard,” said CEO Scott Livengood.

Since the start of the pandemic here, 22 of Alpha’s clients and 42 employees have tested positive for COVID-19. In addition to Sharon Gowdey, one other client and one staff member have died of the virus.

Sponsored

“It’s been extremely difficult to realize you couldn’t protect everyone and keep them as safe as they need to be,” Livengood said.

In an effort to stamp out the virus, last month Livengood put all of Alpha’s King County homes on “containment status” for three weeks. During that time, staff wore full protective gear during their shifts. Currently, he said, none of Alpha’s homes have an active COVID-19 case. But he’s worried about a resurgence or a second wave of the virus this fall.

“We feel like we are prepared for it, and hopefully, if there is a second wave, it’s nothing like we experienced the first time,” Livengood said.

But Livengood said the situation has laid bare inadequacies in Washington’s system of care for people with developmental disabilities. For instance, he said, state reimbursement rates for care are so low that staff are paid barely more than minimum wage.

That creates a situation where the caregivers often work multiple jobs, increasing the potential that they will be exposed to the virus and then carry it to another home.

Sponsored

“Much of this cross-contamination could have been avoided if the state and federal governments provided funding to staff so they made a liveable wage and didn’t have to work two or sometimes even three jobs,” Livengood said.

State officials said they’ve worked with providers to limit the number of staff moving between homes and to educate workers on ways to reduce the chances of COVID-19 spreading. But there’s no ban on the practice.

“It’s not a black and white absolute restriction universally across programs at this point, but it’s certainly an awareness,” Seaman said.

Since April 1, supported living providers have received extra reimbursement to help cover the cost of hazard pay to staff and the procurement of personal protective equipment. But DDA recently announced that federal funding will not continue after July 1.

Livengood said the timing is bad because he expects the state to soon order universal COVID-19 testing of clients in supported living, which will likely result in more positive cases being detected and more homes going into isolation.

Sponsored

“Which requires a different level of support and you need to pay employees more to work in those homes,” Livengood said.

For Kathleen Hesseltine, it's been difficult to make sense of her sister's death because she was generally healthy. Hesseltine recalled that one day they were having lunch in Gowdey’s back yard at a safe distance. A couple of days later her sister was calling her.

“And she didn’t sound right,” Hesseltine said.

Gowdey soon tested positive for COVID-19 and was hospitalized. Since Hesseltine wasn't allowed to visit, she and her sister communicated by FaceTime. Initially, it seemed like Gowdey would make it through. But a few days into her hospital stay, the situation turned dire. Hesseltine said it was unbelievable how quickly the virus took over.

“It’s an awful thing,” Hesseltine said.

Unlike many families, Hesseltine was allowed to be at her sister’s side when she died. Since her sister’s death, Hesseltine has been watching and rewatching the video of her sister on the dance floor last December.

“She loved music and loved to dance and loved her sports. And [she] lived her life the best she could have lived it, I think,” Hesseltine said. [Copyright 2020 Northwest News Network]