Stung By Twitter, Trump Signs Executive Order To Weaken Social Media Companies

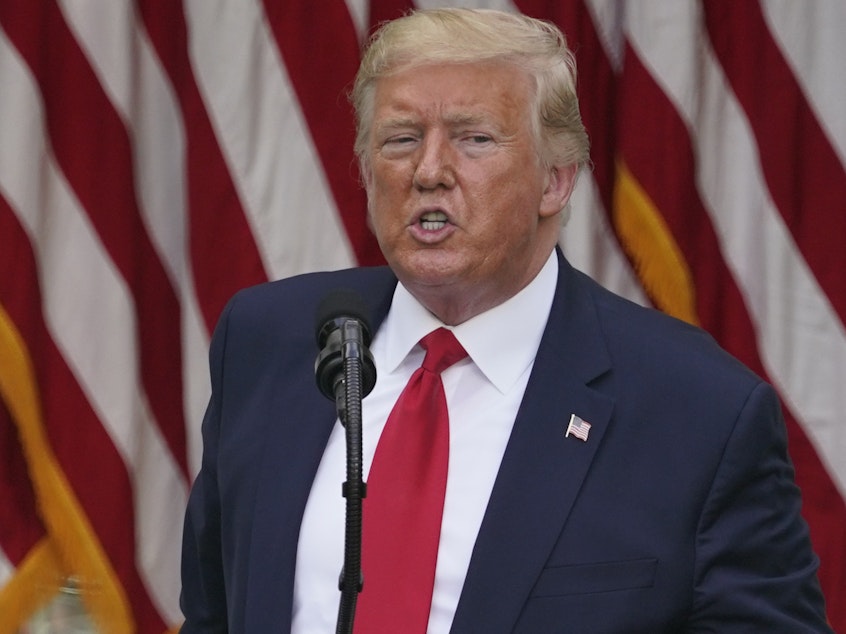

President Trump signed an executive order Thursday aimed at limiting the broad legal protections enjoyed by social media companies, two days after he tore into Twitter for fact-checking two of his tweets.

Updated at 7:55 p.m. ET

"We're here today to defend free speech from one of the gravest dangers it has faced in American history, frankly," Trump said from the Oval Office. "A small handful of powerful social media monopolies control the vast portion of all private and public communications in the United States."

The president said the tech companies have "unchecked power to censor, restrict, edit, shape, hide, alter" a large sphere of human interaction. "They have points of view," he said.

The Trump administration hopes the order will eventually set the stage for new regulations on tech platforms such as Twitter and Facebook.

Sponsored

But legal experts said they were doubtful the move would have any practical effect on the tech giants. Legal observers described the action as "political theater," arguing that the order does not change existing federal law and will have no bearing on federal courts.

The president's latest confrontation with Twitter was set off after the tech company placed fact-checking warnings on two of his tweets that claimed, without evidence, that casting ballots by mail allows for voter fraud. Both Democratic and Republican states have used voting by mail for years without reports of widespread fraud.

Trump lashed out at Twitter, comparing the fact-checking labels to censorship and accusing the social media giant of stifling conservative voices, though the president did not provide any examples to back up his assertion.

The president, who often uses Twitter as a megaphone to tout his victories and blast his critics to his more than 80 million followers, said Thursday that if he had the legal authority to do so, he would completely shut down Twitter.

"I think I'd be hurting it very badly if we didn't use it anymore," Trump said from the White House. "We have other sites we can use, I guess, or we'd have to develop other sites."

Sponsored

Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey said Wednesday that the platform will continue to warn users about factual distortions on it.

"This does not make us an 'arbiter of truth,' " Dorsey wrote on Twitter. "Our intention is to connect the dots of conflicting statements and show the information in dispute so people can judge for themselves. More transparency from us is critical so folks can clearly see the why behind our actions."

Dorsey's comment was an apparent response to Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, who told Fox News earlier Wednesday that social media companies should stay out of the business of weighing in on what is true or not.

"Private companies probably shouldn't be, especially these platform companies, shouldn't be in the position of doing that," Zuckerberg said.

A Facebook spokesperson added that ending the liability shield for social media companies would make sites responsible for what billions of users around the world say.

Sponsored

"This would penalize companies that choose to allow controversial speech and encourage platforms to censor anything that may offend anyone," spokesperson Andy Stone said Thursday.

Regulator: Turning the FCC into "the President's speech police is not the answer"

The White House order takes aim at a 1996 law passed by Congress that has often been at the center of political fights over regulating speech on social media platforms: Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.

The law protects Internet companies from being sued over content that appears on their platforms and allows for content moderation. The removal of a post is left up to the internal rules of companies such as Twitter and Facebook, provided those decisions are made "in good faith."

Courts have repeatedly upheld the law in favor of technology companies, even when the statute was used to defend websites advertising children who were forced into sex trafficking. (In 2018, Congress amended Section 230 to hold websites legally responsible for promoting prostitution or victims of sex trafficking.)

Sponsored

Trump's order seeks to chip away at the vast legal protection Silicon Valley has long fought to preserve by offering a new interpretation of the law. The order argues, in essence, that if the social media companies restrict certain voices on their platforms, the companies should be stripped of their legal immunity, opening the doors to a wave of lawsuits over content seen as defamatory.

Legal experts greeted the order with heavy skepticism, saying, absent a new law passed by Congress, it would not be legally binding.

"It flies in the face of 25 years of judicial precedent, that has been federal precedent in almost every circuit court," said Kate Klonick, a professor at St. John's University School of Law in New York. "It's not the role of the president to interpret federal law."

The order was "a very, very clear piece of political theater," Klonick told NPR, adding that the action is "unlikely to have any kind of weight or authority."

The order directs the Federal Communications Commission to start a rule-making process to clarify when social media companies should keep protections under the law.

Sponsored

Height Capital Markets analysts Chase White and Clayton Allen described the executive order as "mostly noise without any teeth."

In a note to investors, they wrote that the FCC only exerts limited control over social media companies, which are not regulated like traditional broadcasters. And historically, the FCC has been opposed to social media regulation, White and Allen pointed out.

Already, some of the five members of FCC are expressing concern about the White House's action.

"There's this huge thicket of First Amendment issues that it drags the agency into," Democratic Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel told NPR. "Chief among them is the government regulating speech, dictating what can and can't be said online." She warned the order sought to turn the agency into "the president's speech police."

Attorney General William Barr said the White House plans to push legislation to Congress that would seek to reinterpret Section 230 to counteract the sweeping protections granted to large technology companies.

"It's been stretched," said Barr, standing next to Trump in the Oval Office. "And I don't know of anyone on Capitol Hill who doesn't agree that it has been stretched beyond its original intention."

Proponents of Section 230 say both social media platforms and sites like Wikipedia and the Internet Archive would not be able to exist in the same way without the law. If the sites were responsible for everything users posted, the cost of defending against a deluge of lawsuits could prove crippling, advocates of the law argue.

Kate Ruane, senior legislative counsel for the American Civil Liberties Union, called the order an attempt to punish social media companies for posts that displease the president.

"Ironically, Donald Trump is a big beneficiary of Section 230," Ruane said. "If platforms were not immune under the law, then they would not risk the legal liability that could come with hosting Donald Trump's lies, defamation and threats."

GOP's Hawley: Companies that act like publishers should be treated as ones

Backers of Trump's order, such as Sen. Josh Hawley, R-Mo., said adding warning labels to the president's tweets is an editorial decision that shows the social media platform is acting more like a publisher and that the company should lose its special protection.

"It makes little sense to treat companies that publish their editorial comments about others' content as if they are mere distributors. Companies that act like publishers should be treated like publishers," Hawley wrote in a letter to Twitter's Dorsey.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., supports Twitter's initiative to flag tweets that contain falsehoods. She said Trump's order directs the federal government to "dismantle efforts to help users distinguish fact from fiction."

She said the order does not address the proliferation of disinformation on social media, an issue central in the 2016 presidential election and one that's expected to be influential in November.

"Again and again, social media platforms have sold out the public interest to pad their corporate profits. Their business model is to make money at the expense of the truth," Pelosi said.

NPR's Shannon Bond contributed to this report. [Copyright 2020 NPR]