How to bring back a Scottish forest

The wind is really ripping through this valley in the remote Scottish Highlands as I'm zipping along in an ATV. I'm with highlander Innes MacNeil. He’s showing me a few remaining big old trees in the area.

The trees appear like something from a Tolkien novel — remnants of a forgotten time, like a magical connection to the past. There used to be a lot more trees like these across the Highlands. These are anywhere from 250-400 years old — and many are too old to reproduce.

“So these, we would describe them as granny pines,” MacNeil says. “The ones down here in front of us are about 250 to 300 years old, just sat in the bottom of the glen.”

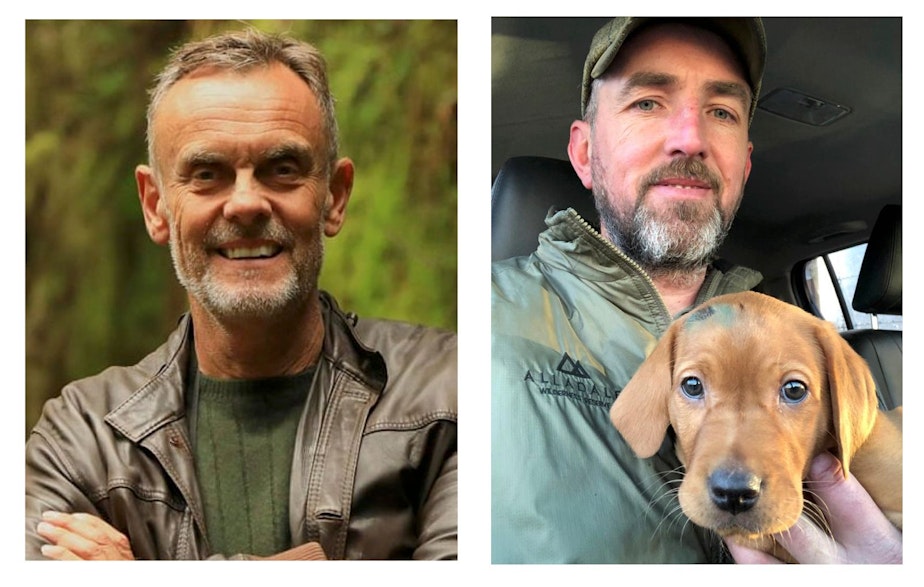

Trees like these once blanketed the region in a thick forest. MacNeil is part of an effort, spearheaded by former businessman-turned-conservationist Paul Lister here at Alladale Wilderness Reserve. An effort to bring back that forest and the ecosystem that it supported.

Sponsored

That’s why they’ve planted close to one million saplings over the past 10 years. That’s why they’ve converted a historic estate into a nature reserve. And that’s why MacNeil has stopped the ATV and is reaching for his rifle.

“So the deer, they do need management," he says. "Clearly, we've taken on the role of the predator."

There hasn’t been an apex predator in the Highlands in more than 300 years, not since the last wolves were seen here. Since then, the deer population exploded . That posed a problem for these tree planters – the deer would eat up a lot of the saplings.

For MacNeil and his team to handle the growing population of deer at the reserve, they have to cull them — selectively kill them.

“So we're reducing the deer population here to find a more harmonious balance between the deer and the habitat restoration,” MacNeil says while spying a herd of red deer in the distance.

Sponsored

This moment is part of a story unfolding in the Highlands. A story with one foot in ancient history and the other hundreds of years into the future. It’s a story about how humans are stepping in, to figure out how to reverse the clock on ecological history; how to bring back a forest and someday maybe even wolves, wildcats, and other critters that once roamed this part of the world.

Culling these deer might be a little uncomfortable and it’s not always an easy thing to explain, especially as an animal lover. But as an ecologist, I’m fascinated by how taking steps like this can really help the ecosystem — the big picture.

The deer are a long way off, but they finally settle. It’s an opportunity for MacNeil to get a clear shot. We lie down on our bellies. They use a rangefinder to gauge the distance. MacNeil considers the wind. In the blink of an eye, two deer are down on the ground. The rest of them are spooked and disappear over the ridge. We then climb up the steep slope towards the deer.

Sponsored

“They know what's going on,” MacNeil says of the deer herds. ”I mean, we've been shooting now since the first of July. So they're quite jumpy.”

For millions of years, red deer learned to be wary of the predators that were out to kill them. And not to be corny, but watching MacNeil and the others, it feels like a wolf pack at work. MacNeil and the guys drag the deer carcass down to the ATV. The meat is taken for human consumption, and the guts are left on the hillside for other species to scavenge -- from eagles and foxes to beetles and worms. They’ll occasionally leave a whole carcass out for the wildlife.

Other animals are learning from this. Ravens, for example, sometimes dozens of them, follow the ATV to kill sites. Just as they would follow wolves once upon a time.

In this moment, standing before me, MacNeil is the wolf of Scotland.

“We're not trying to get rid of the deer,” MacNeil says. “We're just trying to have a better, healthier balance between the deer and the habitat.”

Sponsored

When MacNeil starting working here nearly 30 years ago, he says there were, give or take, 2,500 deer in total at the Alladale area alone. Now there are around 500. That group is healthier and stronger as there are fewer of them to compete with each other.

1 min

Chris describes the glacially-carved valley at Alladale Wilderness Reserve.

1 min

Chris describes the glacially-carved valley at Alladale Wilderness Reserve.

Going back to nature

MacNeil is a highlander, born and raised in this area. His family has worked in sporting estates for generations.

“Historically, these properties were valued on how much death you could create in them,” he said. “So they're valued on the sporting part of a stag; how much he's worth, how many fish you can catch, and how many brace of grouse you can shoot."

Sponsored

These were the long held traditions in the highlands — wealthy hunters come to these mountains to shoot a deer stag. Tweed suits, whisky flasks, the works. They’d pay good money for it. Sometimes several thousand pounds. Having thousands and thousands of deer was good business.

It was the business model that MacNeil knew well. So when Paul Lister showed up nearly two decades ago with talk of a wilderness reserve, instead of a hunting estate, MacNeil wasn’t sure what to make of him.

“And within about three or four months, he put forward his plans and his vision for why he had acquired Alladale,” MacNeil said. “To be honest, I thought he's a little mad.”

But he’s been won over to Listers’s vision and MacNeil is now the Alladale Wilderness Reserve Manager. “Being a Highlander, we love the place, you know,” MacNeil said. “And yeah, we love it for probably all the wrong reasons. We love the big vistas, the big views. And, you know, I know there's an appreciation for it and an understanding that it's not meant to look like this.”

About 2,000 years ago, Scotland looked very different from what you might envision today. There were no sheep, and the rolling green hills were covered with four million acres of ancient forest. It was among these trees that wolves, bears, and wildcats made their homes.

But because of changing weather and especially human intervention, the few old trees seen today are almost all that’s left of those “wilder” times. Today, less than 5% of the forest is left in places like this. These trees are so old that they were around before the last wolf was killed in the highlands back in the 1700s.

“So you could say that they would have probably had wolves cocking their legs against them like, you know, back in the day,” MacNeil says.

The Alladale Wilderness Reserve is an old Scottish estate — 23,000 acres with a lavish main house made of stone. Think a slightly smaller Downton Abbey, surrounded by stone walls, sheep, and big fields and meadows. It all sits in a massive U-shaped valley that was created by glaciers during the ice age.

It’s owned by Paul Lister, who at 60, has loads of energy.

“The vision has always been to take a traditional Victorian sporting estate and turn it into a wilderness reserve, a place of nature,” Lister says.

Lister is from England. His family made millions in the furniture business. He made his first trip up to a northern Scottish estate like this as a much younger man in his twenties. Like a lot of people, he came to hunt for sport.

“And that really brought me up to Scotland,” Lister said. “And then once I pulled the trigger on those deer and the first day, in fact, I kind of thought, ‘What are we doing this for? Why are we doing it? What's it all about? What gives us the right to shoot this big animal like that?’ And then you start to understand the whole breakdown in the fabric of the ecology here.”

These questions eventually lead him to turn his focus on wildlife conservation. He bought Alladale — the house and the huge piece of land — in 2003. That’s when the transformation began.

“So what I want to do is try and do something different instead of continuing on the tradition that Queen Victoria set 150 years ago with hunting, shooting, fishing,” Lister says. “You know, I wanted to change that.”

Long before Queen Victoria was around, about 2,000 years ago, the Romans were suitably impressed with this region as well. They called it “the great wood of Caledon.” It looked much different to what you see today.

“There would be an open area which had been kept open by large browsers and grazers, you know, deer and wild boar would have been here and maybe the Irish elk a long time back,” Lister says. “But it would have been also full of wildlife, you know, real wildlife, like the large carnivores. And if you want to go back over a thousand years ago, there have been bears and lynx here as well. The last wolf in Scotland was probably 300 years ago and that just clung on to very remote glens.”

Except for the deer, all of those species have gone. Lister wants to see this ecological balance restored. This is no small task given the history of how Britain treated its wild places and wild animals.

“Well, I think what happened was that man of Britain, particularly, built an empire,” Lister said. “And in so doing, it came at a price. And that was lots of extraction. We needed fuel, we needed heat. We needed, you know, energy for the factories and in the midlands, for textile industry, whatever way we could. So, you know, timber was an easy source, timber followed by coal. And so, you know, the forest suffered and we weren't replanting, that wasn't happening.”

Those old pine trees that used to be on this property, and all over the north, were cut down. They became ships to fight the Spanish armada back in 1588, and later, railroad ties in Africa. All part of Britain's endeavor to conquer the world. It’s hard to imagine the scale of this relentless devastation. But it’s why there are only a small number of those old trees left in Northern Scotland.

If they can get the trees to come back, the hope is that they can get other species to return as well. They have reintroduced endangered red squirrels to the area, which have thrived. Though an attempt to reintroduce wild boar to the region was not as successful. The land just wasn’t ready yet.

Ultimately, Lister wants bring the land back to a healthy condition so wolves can return.

“So I believe an ecosystem without a large carnivore, you're continually spinning plates like a magician on a stage,” Lister says.

The effort to cull the deer population is just a stop gap measure for Lister. His ultimate vision for Alladale includes a place with wolves. An apex predator, like a wolf, can help keep the entire ecosystem in balance.

In ecology there’s a phenomena called a “trophic cascade.” It involves the idea that having carnivores at the top of an ecosystem helps keep everything below them in balance. Take that carnivore away, and the balance can be upset.

This happened at Yellowstone Park in the United States. After the reintroduction of wolves, there was an ecological knock-on effect that impacted everything from the elk (like the red deer), to beavers, grizzly bears, coyotes, grasses, trees, rivers, and butterflies.

“The minute you bring in a large carnivore, the other things kind of work themselves out,” Lister said.

And that includes the local economy. The wolves in Yellowstone bring millions of dollars in every year from tourism. But Paul isn’t looking to bring wolves back and let them run wild around the Scottish Highlands. Not to start with. He wants to start small.

“I'm more concerned about the first building block, which is to create a one-off wilderness reserve with wolves in it,” he said. “And let's just see what happens. Yeah, you know, let's take it from there step-by-step. And if it works well, then who knows what that might be.”

It’s a bold plan. The area would include all of Alladale Wilderness Reserve, some adjacent land from agreeable neighbors, and a really big fence — around all 50,000 acres. A mini wilderness, managed with a little help from wolves.

But not everyone is a fan of the rewilding plans at Alladale. Not far from the reserve, sheep roam the highlands. They are a big part of the local culture and economy. They are also very attractive to wolves.

So when Paul and his team arrived and started talking about bringing wolves back, it started a bit of a local panic. I spoke to a neighboring couple who did not want to be on mic. One man got physically shaky as he explained he does not favor bringing wolves to the area.

Opposition to wolves is not just from shepherds. Hikers and outdoor enthusiasts are concerned about access to land with a plan that includes fencing in a large section of the Highlands. Even if the land is privately owned, hikers have a “right to roam” in the UK, and many are vocal when fences, and large wildlife species might hamper it. Progress on a project like this is slow. It’ll take decades, even generations, for the pieces of the ecological puzzle to fall into place and flourish in the Scottish Highlands. But already, there are signs that the land is returning to a natural state that no modern generation has known. Very rare pine martens are being caught on remote cameras. Last year, a sea eagle spent the summer at Alladale. There’s even a captive breeding program for the Scottish wildcat.

“There's a rare plant that grows in amongst the old pine forest and it's called twin flower,” MacNeil told me. “Really pretty, a couple inches tall. And just as it's described, it's got two little bells hanging off it.”

The twin flower’s natural habitat is a healthy native pine forest. That’s why it’s rare in the Highlands.

“I’ve been saying to the botanist for the last few years, ‘When are we gonna find some twin flower at Alladale?’ And he said, well, he's never, never seen it here. And anyway, we sort of let it go by.”

Then, just this past spring, the botanist discovered it — twin flower. It was in one of the groves of old pine woods.

“It's a great discovery, you know,” MacNeil says. “…it doesn't sell newspapers. It doesn't you know, it doesn't get the press it deserves. So, you know, it's not all about the big sexy predator. Like, it's about everything, you know.”

You can learn more about the work of Paul Lister and his team at The European Nature Trust.

THE WILD is a production of KUOW in Seattle in partnership with Chris Morgan and The UPROAR Fund. It is produced by Matt Martin and edited by Jim Gates. It is hosted, produced and written by Chris Morgan. Fact checking by Apryle Craig. Our theme music is by Michael Parker.

Follow us on Instagram (@thewildpod) for more adventures and behind the scenes action!