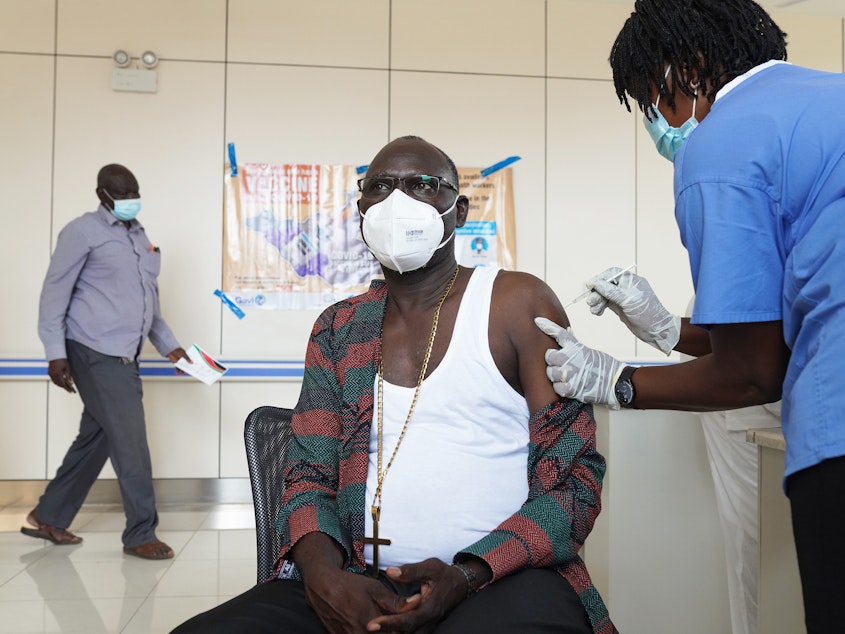

They Desperately Need COVID Vaccines. So Why Are Some Countries Throwing Out Doses?

It seems incredible: At a time when low-income nations are clamoring for vaccines against COVID-19, at least three countries — Democratic Republic of Congo, Malawi and South Sudan — are either discarding doses or giving them to other countries. What's going on?

The answer is something of a paradox. On one hand, with the wealthiest countries snapping up vaccines against COVID-19, the poorest ones remain largely shut out — receiving less than 1% of the global supply thus far. And that's not expected to change any time soon, even with the news on Wednesday that the Biden administration will support lifting patent protections on existing vaccines in a bid to increase their production.

Yet at the same time, some of these low-income countries are struggling to get even the few doses they have received into people's arms before the vaccines expire.

Emily Janoch, with the aid group CARE, has been tracking what's happened to the COVID vaccine doses that have been trickling into low- and middle-income countries since February through COVAX (the initiative led by the World Health Organization), as well as, in case of African nations, a similar, but separate purchasing effort by the African Union.

Janoch says that while several of the countries, such as Ghana and Rwanda, gave their shots to people almost immediately, quite a number of others are taking a while.

Sponsored

"What we found is that a lot of countries have received doses, but haven't administered them yet, or haven't administered a significant proportion of them yet," says Janoch.

For instance, 24 countries, almost all in Africa, report using less than a third of their vaccines to date. Of those, 15 report using less than a fourth.

Officials and aid groups involved in vaccine deployment in these countries point to two main reasons: There hasn't been enough international help to cover the logistical costs of vaccination. And there's been a surge in distrust in the wake of recent news about extremely rare but potentially deadly side effects from some of the vaccines available to the continent.

In Malawi, for example, demand for the vaccine seemed high at first, says Amos Zaindi, CARE's country director. He remembers driving around the capital, Lilongwe, and seeing people waiting in long lines outside the vaccination centers.

"In those days when vaccination was at the peak, you could go to the vaccination center and it would take you two to three, even four hours [to get a shot]," he says.

Sponsored

Then came the news in early March that several European governments were suspending use of the AstraZeneca vaccine over reports of blood clots in a small number of people.

AstraZeneca is the vaccine Malawi is using. Among people there — particularly young, social media-savvy people — the news of Europe's doubts "spread like wildfire," says Zaindi. "You know it's a global village. When information is generated in Europe or in the Americas, it generally takes a matter of seconds [to reach Africa]. Everyone gets it. And that discouraged many of our young people."

Seemingly overnight, says Zaindi, the lines outside the vaccination centers in the capital evaporated.

Since then, Europe's regulatory agency has advised that AstraZeneca is still safe and effective — and that its benefits far outweigh its risks. Zaindi thinks that's all the more true for Malawi, where AstraZeneca is currently the only option.

Yet people in Malawi remain so distrustful, Zaindi says he's having a hard time convincing even his own staffers at CARE to get vaccinated. So far only about 40% have done so.

Sponsored

"These are staff that are educated, that are learned," says Zaindi. "But they're still getting all these confusing statements from Europe and the Americas. And it's confusing them in terms of making a decision."

Emily Bancroft, CEO of VillageReach, a nonprofit that partners with various African countries including Malawi to help with vaccine delivery logistics, says the skepticism around the vaccine exacerbated the other big difficulty facing Malawi: limited funding to prepare for the rollout.

Ideally, notes Bancroft, before low-income governments launch vaccination campaigns they lay the groundwork. This includes everything from educating the population to setting up the systems needed to anticipate and track how many doses will be needed among different distribution sites.

But that kind of advance preparation was hard to do given the ad hoc nature of vaccine distribution to low-income countries — with doses being distributed in fits and starts and with little clarity on how much Malawi could count on the international community for operational funding.

"It's hard to prioritize planning — and to mobilize the resources — when it's not clear what the sources of funding will be," says Bancroft. So this slowed down the rollout.

Sponsored

The upshot of that delay, combined with the hesitancy problem: Malawi's government recently had to destroy 16,000 doses of vaccine that expired before they could be used.

CARE's Zaindi says he was in his office when heard the news from an official at Malawi's ministry of health. "I was like, Oh my God, we have just lost 16,000 lives that could have been saved. It's so painful!"

Adding to the drama, the vaccine's manufacturer, Serum Institute of India, announced that the official expiration could actually be safely extended. But Bancroft said their advisory came too late. "Unfortunately health workers had already taken the vaccine out of the cold chain to be destroyed."

Still, Malawi has at least managed to use about 60% of its vaccine supply.

Even more dire is the situation in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Its government received 1.7 million doses of AstraZeneca in early March, but held off on using them while waiting for new guidance after the blood clot issue.

Sponsored

Ultimately, Congolese authorities determined that it still makes sense to use the vaccine. But by that time, they estimated that it would be logistically impossible to give most of Congo's shots in the few weeks before they were set to expire.

Congo's health system, explains Janoch, is not a strong one. "It's not one that has had many long-term, big investments. And it is hard to mobilize this kind of a massive campaign with a completely new population that typically doesn't get vaccinated in such a short time."

Congo says it will hand over about three-fourths of its vaccine to other countries. South Sudan, in a similar bind, has announced it will discard 60,000 doses that have already expired.

It's worth noting, adds Janoch, that these difficulties have arisen at a stage when African countries have received only a tiny fraction of the vaccines they need. She says it suggests the delays and disruptions could be far worse once African countries can finally obtain more reasonable quantities.

The takeaway, says Janoch, is that wealthy donor countries and organizations need to put a lot more money and effort not only into purchasing vaccines for low-income countries — but into funding the logistical side of vaccine delivery once the doses are on the ground.

"About half of that [funding for logistics] needs to go to health care workers — to their salaries, to supporting them, to training them," adds Janoch, who has authored a report estimating the likely cost.

A big problem says Janoch is that those expenses are hard to calculate and were largely left out when the major multilateral organizations involved in the COVAX initiative — including not just the WHO, but UNICEF and GAVI — estimated the operational costs. Instead, when it came to the delivery side, they have mostly focused on raising money for bolstering the cold chain capabilities of poor nations. And to date, even those far more modest targets have barely been funded. [Copyright 2021 NPR]