Taming speed on the Speedway (and other Washington roads)

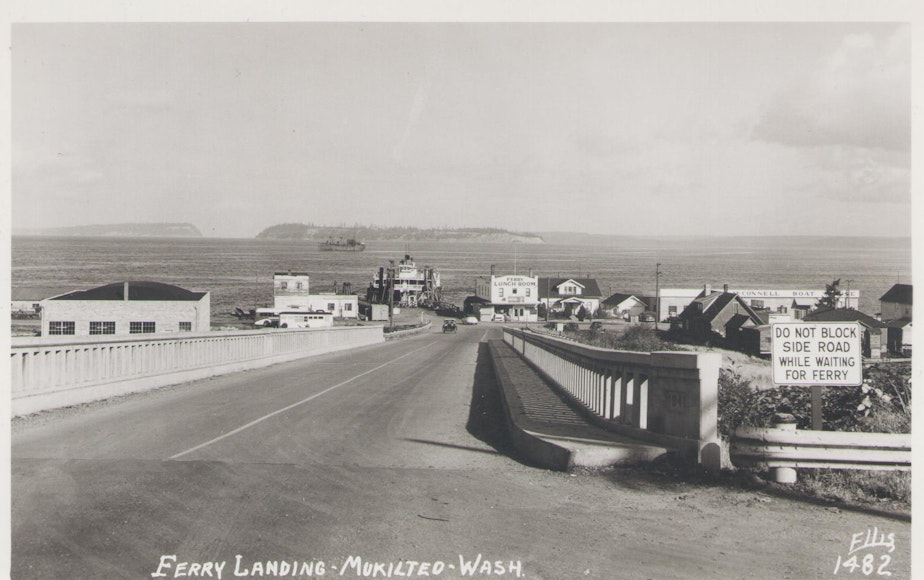

Many American roadways are built for speed. One road north of Seattle is even named for it: the Mukilteo Speedway.

It may sound like a racetrack, but the Mukilteo Speedway is actually a suburban highway, state Route 525. It is the main route into the bedroom community of Mukilteo and to the Mukilteo-Clinton ferry to Whidbey Island.

How the Speedway got its unusual name about a century ago may be lost to history. One of several theories, according to the Mukilteo Historical Society, is that it was considered a speedier way to get to Seattle than the bumpy lumber “skid road” it replaced around 1925.

In December, the Mukilteo City Council voted to install four automated speed cameras along the Speedway.

When Mukilteo police proposed cracking down on lead-footed drivers by installing cameras to photograph the license plates of speeding cars, some residents took it as an assault on the waterfront town’s quality of life.

At a city council hearing in December, Bob Templeton of Mukilteo called the proposal a “money grab.”

Sponsored

“Mukilteo’s a pleasant place to live,” Templeton said. “We don’t need to be extracting millions of dollars from our friends and neighbors, and our neighbors on Whidbey Island, and the people that come up and down the Speedway. And they haven’t done anything wrong. Well, maybe they exceeded the speed a little.”

Elementary school teacher Linda Wooding called speed cameras “nanny cams.”

“We don’t need to be told what to do like that,” she said.

Wooding said she didn’t want her town to become like Lynnwood. The neighboring suburb has two speed cameras and eight intersections with red-light cameras.

“I’m a fan of them,” Lynnwood Police Chief Cole Langdon told KUOW. “They do modify people’s behavior.”

Sponsored

“I'll do anything not to drive through Lynnwood. I stopped going there,” Wooding told the city council. “It’s not a nice place because you’ve got to be really careful. You do nothing wrong, and you get in trouble.”

Of course, speeding is lawbreaking, with potentially deadly consequences, and not just in Lynnwood.

At least 22 jurisdictions around Puget Sound use speed cameras or red-light cameras, according to the Puget Sound Regional Council.

Washington state is launching a pilot to use speed cameras near highway construction zones to keep workers safe.

Speeding has skyrocketed since the Covid pandemic, according to the Washington Traffic Safety Commission. So have deaths from car crashes.

Drivers killed at least 763 people in Washington in 2023, the highest death toll since 1990. About a third of drivers involved in fatal crashes were speeding at the time.

Mukilteo Police Chief Andy Illyn told the city council that the Mukilteo Speedway has seen dozens of crashes in the past five years, but no deaths.

“That's what we're trying to prevent,” Illyn said.

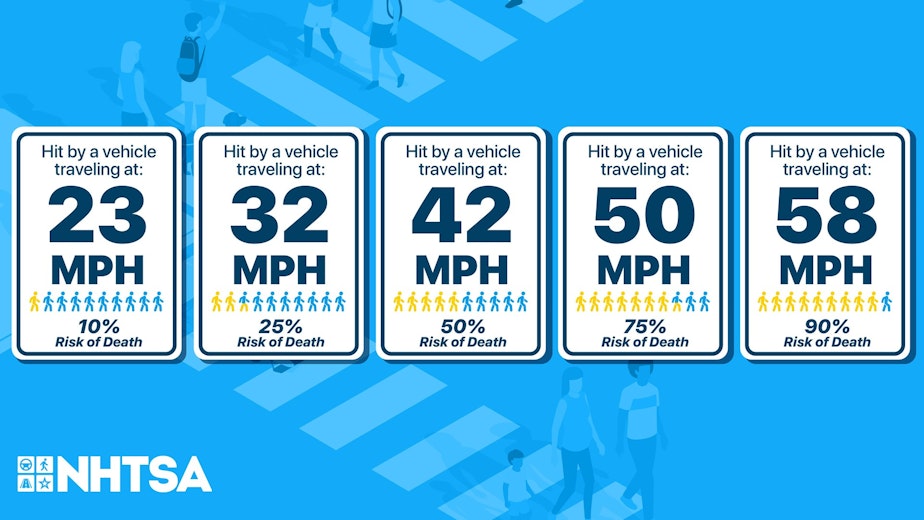

He said drivers had been clocked going through the Olympic View Middle School 20 mile-per-hour zone on the Speedway at up to 47 miles per hour.

“A kid hit by that is a kid that's probably not going to survive,” he said.

Sponsored

Illyn said cameras can do a better job at catching speeders than human cops can. And they can free up his understaffed department to fight crimes.

Sponsored

“There's some agencies that won't come out for residential burglary unless over $10,000 has been stolen,” Illyn said. “That's not how policing should be done.”

Beyond the privacy issues around cameras, any effort to get America to slow down is swimming against a lot of popular culture.

Speeding is a form of lawbreaking that is widely committed and celebrated in everything from blockbuster movies to auto industry ads.

Dodge ads refer to the company’s “Never Lift philosophy”: “keeping a foot firmly planted on the gas pedal.”

“We never lift, and we never will,” one Dodge ad states.

Sponsored

Of course, never lifting your foot off the gas is an excellent strategy for getting yourself or somebody else killed.

“How many deaths will it take before we decide to take seriously actions and then act?” National Transportation Safety Board chair Jennifer Homendy asked at a hearing in November on an especially deadly crash in Nevada in 2018.

“If I sound outraged, it’s because I am,” she said.

A Dodge driver high on cocaine and angel dust sped through an intersection in North Las Vegas at 103 miles per hour, killing nine people, including himself.

“Dodge emphasizes speed and encourages drivers to never lift their foot off the gas pedal,” Homendy said. “That sort of advertising is dangerous. It contributes to a culture of speeding, and that culture can cost people lives, as it did in this crash.”

Homendy called the thousands of annual deaths on U.S. roads a “a total system failure.”

Following its review of the North Las Vegas crash, the Transportation Safety Board recommended that all new cars have anti-speeding technology that would, at minimum, warn drivers when they are exceeding a local speed limit.

The European Union required the technology, known as known as intelligent speed assistance, in new car models in 2022 and in all new cars in 2024.

Intelligent speed assistance is available as an option on about 20 car models in the United States, according to the safety board.

Some cars beep or give other indications, such as more resistance from the gas pedal, when a driver goes over the local speed limit.

“Please obey all traffic regulations,” some Toyotas warn their drivers when they start to speed.

Other intelligent speed assistance systems take more active measures, similar to cruise control, to let up on the gas and slow a car down.

The Washington State Department of Transportation is conducting a one-year test of intelligent speed-monitoring technology in its fleet, adding it to 50 sedans.

The King County Council is considering whether to try the technology in the county’s vehicle fleet too, after conducting a feasibility study of the technology in 2023.

Beyond saving lives, the technology could also save on gasoline and pollution, since cars tend to run most efficiently below 55 miles an hour.

Safety officials say getting Americans to accept internal speed-limiting technology could be hard.

Homendy said a good place to start is with parents.

“As the mom of a teenager who, today, is getting her learners’ permit, I would be right in line for ISA technology to make sure she was safe,” Homendy said.

In Europe, the in-car technology has been marketed as a good tool to avoid speeding tickets from the continent’s many speed cameras.

In Mukilteo, police hope to have that city’s first speed cameras in place along the Mukilteo Speedway this summer. Police say Florida-based contractor NovoaGlobal and a Mukilteo police officer will review photos for accuracy before issuing any citations to vehicle owners.

Mukilteo officials expect to use revenue from speeding tickets to further improve public safety.

“I do also see the value of having of having additional revenue, given the lack of sidewalks and the lack of pedestrian safety that we have in the city, when we as a city deserve that,” Councilmember Louis Harris said.

Many transportation experts say the sure-fire way to slow traffic down to safer speeds is to redesign roads with “traffic calming” features like speed bumps and traffic circles that force drivers to hit the brakes.

Full disclosure: I once got a speeding ticket on the Mukilteo Speedway, on my way to catch a ferry, and am embarrassed to admit I once got a speed-camera ticket in a school zone in Seattle: I’d failed to notice a flashing school zone sign or slow down to the required 20 miles per hour.