Did Grandma bring coronavirus to the Kirkland nursing home? A family weighs the evidence

Grandma lay on the bed, her eyes open and vacant. She wore a thin, white hospital smock dotted with small flowers and held her granddaughter’s hand as afternoon light enveloped the room.

The heart monitor beeped, and at the foot of the bed, her grandson stumbled through the Book of Isaiah. He was not religious, but Grandma was, and Isaiah was where the ribbon rested in her black Bible.

Like others in the room, the grandson wore a yellow mask and yellow gown — protective gear issued to them by the nurse at EvergreenHealth community hospital in Kirkland, Washington, because Grandma was in respiratory isolation.

Grandma was the matriarch: unapologetically loud about her love for her seven children and 19 grandchildren, many of whom came to visit her at the hospital. When Grandma’s youngest daughter walked in the room, she saw that her 89-year-old mother was fading.

She rushed to her, put her forehead to her mother's, and pleaded. “Are you with me? Come back. We’re here.”

The daughter wore a mask but had missed the nurse’s tutorial, and was not as protected as the others.

Sponsored

“I’m tired,” Grandma said, and stuck out her tongue, as though pleading for moisture. It was dry like sand paper.

“She needs water,” her daughter said, and went to fill a paper cup. She held a yellow straw to her mother’s mouth. Grandma drank four more cups after that.

It was February 2.

Grandma would mostly recover over the next two weeks at Evergreen. Food would taste like metal, making her shudder, and she would cough a lot, but she survived.

“A blessing or a curse, I don’t know,” the grandson would say with hindsight.

Sponsored

E

arly in Grandma’s hospital stay, a family member asked a nurse if Grandma might have coronavirus. The question was waved off.

After all, there was just one person in the U.S. known to have Covid-19 — a 35-year-old man from nearby Snohomish County who caught it traveling in Wuhan, China, the global epicenter of the virus. He was recovering at Providence hospital in Everett on a ward built for an Ebola outbreak. His nurses wore protective helmets and face shields, and a robot took his vital signs.

And anyway, the lab tests said Grandma had metapneumovirus, an upper respiratory disease. A bad cold.

She wasn’t tested for coronavirus because hospitals hadn't received tests for it at that time -- even though there was a case nearby.

Sponsored

“That’s the sad thing with this,” said Grandma’s eldest daughter, a nurse at Harborview Medical Center. “No one was testing in those early days.”

On Thursday, February 13, Grandma was wheeled into her new room at Life Care Center of Kirkland, to recover from her hospital stay. She had a roommate: A woman, age 87.

Grandma knew nursing facilities; she’d been a night shift nursing supervisor at one on Queen Anne Hill in Seattle, working full time until age 70.

Life Care, one-story, beige, and surrounded by towering fir trees, was more modest, but welcoming. Residents chatted in the corridors and dining hall, and participated in group activities, like a Mardi Gras party. Guest logs showed pages of visitors.

Grandma’s eldest daughter sent her siblings a text: “Hey, we made it to the rehab facility,” she wrote. She attached a photo of Grandma smiling from a single bed, white blanket tucked snug around her chest, yellow walls as a backdrop.

Sponsored

KUOW is not naming the family to protect their privacy. Grandma was not interviewed because, according to family members with medical power of attorney, Grandma is not cognitively able to participate in this story.

T

hree weeks later, the grandson, the one who had read Isaiah, called me.

He had a hunch that his grandmother had brought coronavirus to Life Care and, in doing so, had started the first Covid-19 outbreak on U.S. soil.

Contact tracing — the painstaking detective work of tracking a virus — had fizzled within days of the Seattle-area outbreak, despite the World Health Organization touting its importance for containing spread. Workers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had initially looked into Life Care residents who got sick, but hadn't examined those who were not.

Sponsored

Dr. Juliana Grant, a medical epidemiologist in Seattle, said looking for the original source could “identify opportunities for improvement.”

“You can look back at something retrospectively: ‘This should have been caught here. Here’s why it wasn’t,’” Grant said. “We don’t want to blame individuals. We want to improve our systems.”

The grandson wanted to know his family’s role in the outbreak and to share their devastating experience with the virus. It was too late for the Seattle area, but maybe someone elsewhere would read this story and glean something from it that would save lives.

At Life Care, one in four of the residents would die of coronavirus inside a month. From there, the virus spread to other nursing homes in the Seattle area, and to North Carolina, where there are now more than 630 reported cases.

To date, 132 people have died of coronavirus in Washington state, nearly a third of them from Life Care.

A

s Grandma improved at Evergreen, and then Life Care, her youngest daughter, who was 48, got sick. A splitting headache that lasted three days, and a fever. Her lungs seemed to fill with fluid, and she could hear gurgling in her chest, as though a demon were speaking to her. Crackling and popping, and bubbling, especially when she lay down.

She took Tylenol, unable to push her fever below 101 degrees. Food tasted like metal, as it had for her mother. She isolated herself in a room at her home in eastern Washington, and told her husband to stay away. I got what Mom had, she thought to herself.

Meanwhile, at Life Care, other members of Grandma’s family came to visit. They took shifts: the first week went to her son, an Uber driver, the second to the eldest daughter.

Her beloved in-home care provider also visited, and fed Grandma three french fries and water.

But it was Grandpa who came most often. They had been married 67 years and were still deeply in love. One night before Grandma went to the hospital, they slept upright on the couch, holding hands until morning. They were affectionate, kissing often despite their ailments. On Facebook, Grandpa posted two photos of his bride on her 85th birthday. “I think she looks great!” he wrote.

At Life Care, Grandma’s visitors did not wear gowns or masks as they had at Evergreen. After all, Grandma had recovered and was no longer contagious – for the cold, anyway.

F

ebruary 18, five days after Grandma arrived at Life Care, saw the first person in respiratory distress sent to Evergreen hospital for that month — a woman whose symptoms came on five hours before an ambulance was called.

And then Grandma’s visitors got sick, one by one.

February 19: Grandma’s son, the Uber driver, texted his siblings that he was not feeling well. He would later be hospitalized and test positive for Covid-19.

February 21: Grandma’s eldest living son, a retired arborist, got a fever. At Life Care, he had held his mother’s hand and kissed her cheek. He tested positive for Covid-19. This son believed in the power of herbal medicine, and credited his quick recovery to a tart combination of ginger juice, squeezed lime, cayenne, licorice root, and boiling water.

February 26: Grandma’s roommate was no longer in her room. According to county death records, the roommate died March 6. She would be one of six Life Care residents to die that day.

February 29: Grandma’s eldest daughter got a fever and would later be hospitalized. She tested positive for Covid-19.

March 1: Grandpa became ill, and dangerously dehydrated. He would be hospitalized and test positive for Covid-19.

The siblings had little contact with each other in February.

“I didn’t see any of my other brothers or sisters who got sick ... I didn’t get it from them,” the eldest daughter said. “The only common denominator is the facility.”

Another denominator: Their mother.

How could a respiratory virus ravage a nursing home, her brothers and sister, and not snare her frail, 89-year-old mother, the eldest daughter wondered?

“There’s no explanation for how she sailed through this while the rest of us got sick,” she said. “It points to her being the first.”

It is not possible to definitively answer the family’s question – was it Grandma? There were many others at Life Care — visitors, social workers, traveling staff — who could have brought it in.

Still, lab reports, ambulance logs, interviews with five family members, the in-home care provider, and consultation with four medical experts — an infectious disease doctor, an epidemiologist, a geneticist, and internal medicine doctor — suggest that it was reasonable to believe that Grandma was Patient 0 at Life Care.

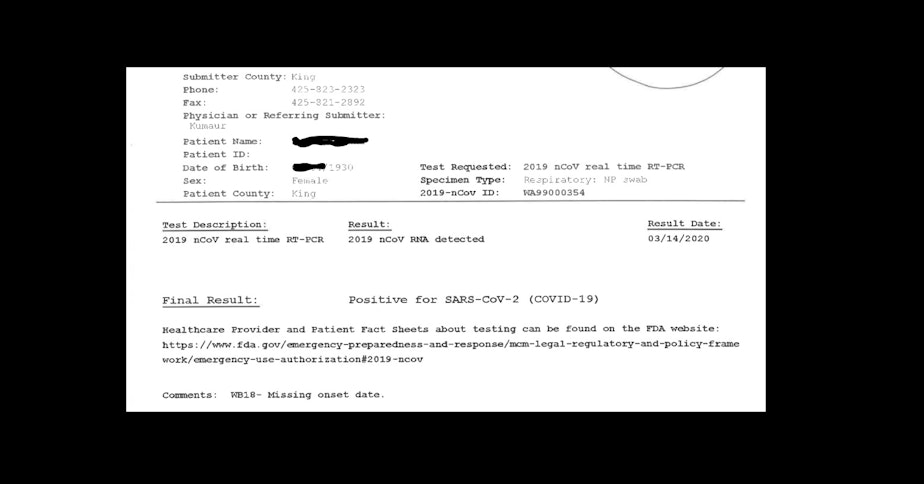

And then … Grandma tested positive for coronavirus. It was March 11, nearly one month after she arrived at Life Care.

Grandma’s younger daughter wanted to know what this meant. Would her mother become very ill in coming days? Or had she been sick with coronavirus in early February – and the illness remained in her system?

That was a possibility: Coronavirus has been found to stay in a person’s body for more than a month after symptoms start.

The doctors consulted for this story said to watch Grandma. If she became sick in coming days, she probably was not Patient 0.

If she remained symptom-free, it was more likely, they said. The epidemiological story fit. It simply did not make sense for an elderly woman, prone to bronchitis her whole life, to stay healthy when everyone around her got coronavirus.

It has been more than two weeks, and Grandma remains symptom free.

“It is interesting that she tested positive for coronavirus but never did get sick,” said Dr. Grant, the epidemiologist. “And that so much of her family got sick.”

She believes it’s plausible Grandma was the source.

“There were other patients who arrived at the same time, I’m sure, but there are a number of things that seem to line up,” Grant said.

She said she found it noteworthy, too, that ambulance calls for respiratory distress started roughly five days after Grandma arrived – the average incubation period for coronavirus. There hadn’t been respiratory distress calls in February before Grandma arrived.

I

f Grandma brought coronavirus to Life Care, as some of her relatives suppose, how did she get the virus?

We know that the coronavirus strains from Life Care have been traced back, genetically, to the Snohomish man. There were two weeks between when the Snohomish man returned from China on January 15 and when Grandma was admitted to Evergreen. How could the virus find its way to her, a woman who lived alone with her husband and rarely left the house?

The people around Grandma have theories – although they concede there is no way to know for sure.

Grandma had visited a cardiac clinic affiliated with EvergreenHealth the week before she was admitted to the hospital. Perhaps she caught something there?

Grandma’s son, the Uber driver, drove to the airport. Had one of his passengers been infected? But that was a stretch; he got sick much later.

The in-home care provider had coughed for three or four days in January, and she attended a church in Everett, the city where coronavirus was known to have spread quietly. But coughs are common in winter, and Everett is a big city. That too was conjecture.

Or maybe Grandma wasn't the source.

Jeffrey Duchin, a health officer for Public Health — King County & Seattle, said on Wednesday that no one knows how coronavirus arrived at Life Care.

“At the time they reported [an outbreak] to us, the illnesses were occurring at least two weeks prior,” Duchin said.

Staff could have brought it in, he said, or visitors. Or a resident who had unknowingly been in touch with a traveler.

Or, he continued, it could have been a resident, discharged from a hospital, who brought the virus with them to Life Care.

“We don’t know for sure,” he said. “But we do know that it was one of those.”

KUOW's Ashley Hiruko and John Ryan contributed research.