What Happens When A Country Bans Spanking?

In 1979, Sweden became the first country to ban the corporal punishment of children. Earlier this year, Nepal became the 54th country to do so.

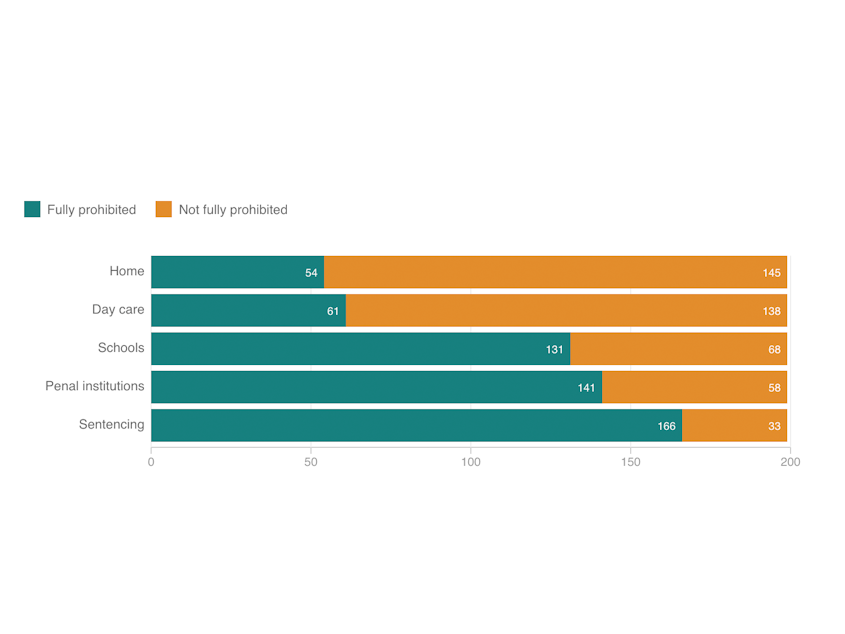

Don't see the graphic above? Click here.

Now a new study looking at 400,000 youths from 88 countries around the world suggests such bans are making a difference in reducing youth violence. It marks the first systematic assessment of whether an association exists between a ban on corporal punishment and the frequency in which adolescents get into fights. And, says Frank Elgar, the study's lead author and an associate professor at the Institute for Health and Social Policy at McGill University in Montreal, "The association appears to be fairly robust." The study appeared in the online journal BMJ Open.

Of the countries included in the study, 30 have passed laws fully banning physical punishment of children, both in schools and in homes. The rates of fighting among adolescents were substantially lower than in the 20 countries with no bans in place: by 69 percent for adolescent males and 42 percent less for females.

The other 38 countries in the study — which include the United States, Canada, and the U.K. — have partial bans, in schools only. In those countries, adolescent females showed a 56 percent lower rate of physical fighting, with no change among males.

Sponsored

The data on fighting came from the World Health Organization's Health Behavior in School-aged Children study and Global School-based health survey. These long-standing surveys of teen behavior included a question about whether, and how often, the teens had been involved in a physical fight in the past 12 months.

The association held true even after accounting for such factors as the differences in the wealth of the countries and the nation's homicide rates, said Elgar. Even so, Elgar cautions, the study shows a correlation only, not a cause and effect.

"It could be that bans come into place in countries that have already generally accepted that spanking is not the best discipline method," he said, or there may be other cultural factors involved. "We haven't answered with certainty" the impact of the bans, he says, noting that more research is needed.

What research does show is the negative consequences of spanking. Physical discipline is not only ineffective, but it can also cause harm, says Elizabeth Gershoff, a professor of human development and family sciences at the University of Texas at Austin who has been studying the impact of physical punishment on children for 20 years.

In 2016, Gershoff and a colleague conducted a meta-analysis of 50 years of research on spanking, encompassing about 160,000 children.

Sponsored

"The findings were consistently negative," she said. Although spanking is traditionally supposed to teach a lesson to correct bad behavior, children who were spanked were neither more compliant nor better behaved.

Moreover, for both boys and girls, she said, "We found [spanking] linked to more aggression, more delinquent behavior, more mental health problems, worse relationships with parents, and putting the children at higher risk for physical abuse from their parents."

"People often ask: Why didn't you look for positive aspects?" she continued. "My answer is: We did, and there were none. We see consistently that the more children are spanked, the more behavioral problems they have in the years ahead."

UNICEF senior data specialist Claudia Cappa, believes the study provides additional support for the idea that "violence teaches violence."

"A child exposed to violence at home is very likely to use violence against peers in school" and in later life as well, she says. The reason is that when children are spanked or slapped, she says, "they think that is the only way to address conflicts, that there are no alternative means" to working out a disagreement besides fighting, and as they grow and develop, they can start to interact with their peers in the same way.

Sponsored

The prevalence of physical punishment — its most common form being spanking, also called slapping — was highlighted in the 2017 UNICEF study authored by Cappa, A Familiar Face: Violence in the Lives of Children and Adolescents. The report found that, globally, about 300 million children between the ages of 2 and 4 experienced physical punishment or verbal abuse from their parents of caregivers, and in some countries, children as young as 12 months old were subject to hitting.

Given the prevalence and the repercussions, a number of human rights groups, including the United Nations, have condemned the practice. In 2006, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, or UNCRC, spelled out "the right of the child to protection from corporal punishment and other cruel or degrading forms of punishment" and continues to recommend prohibition against corporal punishment of children.

Legislated bans send a clear message that this kind of discipline is not acceptable, says Cappa. But to be effective, bans need to be paired with programs that help parents learn what to replace corporal punishment with. "Parents may think, this is what my parents did to me or is expected of me," she says, and they are not aware that alternative strategies exist and are more effective. UNICEF, Save the Children and other organizations have helped put in place programs in a number of countries to promote such approaches.

"Discipline means teaching, and sometimes that involves modeling behavior," such as using words to express disagreement and talking things out to find a solution, says Gershoff, who is completing a book about how to reduce physical punishment, aimed at psychologists, community organization leaders and policymakers. It also means praise when children do something we like, she says, "because that is the best way to increase the likelihood that will happen again."

As for countries and territories that do ban corporal punishment in all settings, they run the gamut of all income levels. They include:

Sponsored

A number of Latin American countries (including Bolivia, Brazil and Nicaragua)

A number of European countries (including Germany, Poland, Spain and Scandinavian countries)

Former Soviet republics (including Turkmenistan and Ukraine)

Several African nations (Benin, Gabon, South Sudan and Tunisia)

Also: Mongolia and New Zealand

Sponsored

You can find lists and maps here.

Diane Cole writes for many publications, including The Wall Street Journal and The Jewish Week, and is book columnist for the Psychotherapy Networker. She is the author of the memoir After Great Pain: A New Life Emerges. Her website is dianejcole.com. [Copyright 2018 NPR]