Where there’s a whale, there’s a way. Keeping field science going in a pandemic

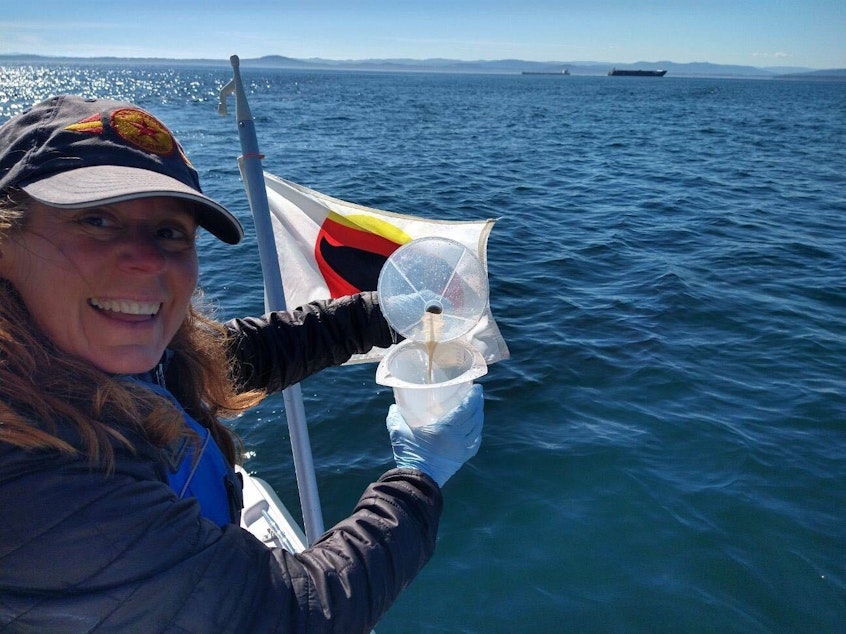

Deborah Giles hasn’t been able to let her usual crew onto her small research boat this year.

To keep her research on the Northwest’s endangered orcas going despite the coronavirus pandemic, the whale biologist has recruited within her household bubble.

Now her husband Jim Rappold and their specially trained dog Eba make the team.

While Rappold drives the boat, Eba stands on the bow and sniffs the salt air for hints of orca feces – full of hormonal and chemical clues to the orcas’ well-being – bobbing in the water.

As Rappold steers, Giles works with Eba and quickly processes scat samples she scoops out of the sea. Every 30 minutes, she also records data on any interactions between the orcas and nearby boats.

“Normally I have somebody that's just dedicated to that. This year, I just have to set a timer and do it myself,” said Giles, a researcher with the University of Washington Center for Conservation Biology.

Researching whales is never easy. The wide-ranging mammals pop up only briefly and unpredictably from their vast ocean home.

The Covid-19 pandemic has made it that much harder.

Budget constraints, travel restrictions and laboratory closures have put a lot of wildlife biology on hold.

But whale researchers in Washington have also reengineered their work to keep critical science going despite the life-or-death need for most humans to avoid each other.

No longer able to work side by side, biologists have streamlined what they do.

Sponsored

John Calombokidis with the Cascadia Research Collective monitors gray whales in Puget Sound. He now does much of his fieldwork solo.

“I have to drive the boat, take data, take photographs and collect some of these skin samples by myself,” Calambokidis said. “But I kind of like doing that.”

Wearing a small video camera on his head also helps with the data collection.

Any other year, the research collective would send teams of 5 to 10 people out to do post-mortems on whales that wash up dead on Washington beaches.

This year, it’s two to four people, and no carpooling, according to Jessie Huggins, Cascadia’s stranding coordinator.

Sponsored

“It’s a lot more physical work for the people doing it now,” Huggins said. “Instead of two people helping you peel back a piece of blubber, you have one person.”

One advantage of working with whales like grays and humpbacks: They’re so big that safely distanced biologists can simultaneously examine different parts of a 40-foot carcass.

The continued post-mortem work has established that 2020 has not been nearly as deadly for gray whales as the unusually lethal year before: Only 12 washed up dead in Washington versus 34 in 2019, according to Huggins.

Holly Fearnbach with Sealife Response, Rehabilitation, and Research didn’t have to steal her husband away from his day job: She and John Durban, both whale biologists, have been working together for more than a decade.

Sponsored

Still, they’ve had to cancel field work in the Gulf of Alaska and the North Atlantic this year and let some endangered whales go unstudied.

Closer to home, she and Durban have been able to continue documenting the health of orcas with aerial photographs from a drone operated from a small research boat.

For their work on southern resident killer whales, travel hasn’t been a problem: the couple lives on the westernmost of the San Juan Islands, Stuart Island (population: 20). When they get word that orcas are in the vicinity, they just have to get down to the nearby docks.

They have had to pare down their research crew to just the two of them.

“We adapted,” Fearnbach said. “We figured out how to do it.”

Sponsored

Fearnbach now drives the boat as well as monitoring the data coming back from the drone that Durban remote-controls.

From those aerial images, they can see when orcas are undernourished and when they are pregnant, vital information for the international effort to bring southern resident orcas back from the brink of extinction.

Should the whales venture across the border into Canadian waters, it’s not an insurmountable problem for U.S. researchers.

While the border with Canada has been closed to most Americans since March, researchers with permits can boat into Canadian waters – as long as they stay offshore.

A team of four on San Juan Island has been studying orca behavior without traveling far or even stepping onto a boat.

The Oceans Initiative crew sets up high-powered optical instruments on the island's coastal bluffs to document the whales’ behavior, even miles offshore.

The quartet acts as one unit as far as Covid-19 goes.

“The four of us live together, work together, hang out together. So we're definitely an isolated pod,” research assistant Andrea Mendez-Bye said.

She said they wear masks everywhere they go on-island and keep distance from others at the farmers market and grocery store.

“We try our best during this crazy time,” Mendez-Bye said.

Deborah Giles said for her, there’s a bit of a silver lining to the pandemic.

In prior years, Rappold had filled in as a back-up boat driver when Giles couldn’t be there herself. But the couple had never worked together until Covid-19 prevention made it necessary.

“We've been enjoying the opportunity to spend the time together,” Giles said. “We feel fortunate that we have the chance to continue the work, that this [long-term] study didn't have to stop because of Covid.”

While Rappold isn’t a biologist, he is a skilled boat captain. In case a call comes in that the elusive orcas have been spotted nearby, he keeps a “go bag” with him at his job renovating old houses.

Giles said Rappold’s boss at Shelterra Design Build has been very supportive when his employee asks to suddenly drop everything so his wife’s critical research on an endangered species isn’t left high and dry.

"He just gets these great texts back from his boss, 'Go get 'em,'" Giles said. "It really does take a village."