Why low income countries are so short on COVID vaccines. Hint: It's not boosters

There have now been more than 250 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 worldwide. That's according to tracking by Johns Hopkins University. This milestone comes as wealthy countries have fully vaccinated about 65% of their populations. Yet in low-income countries fewer than 3% of people have been vaccinated. Analysts say a major reason for the inequality: Month after month rich countries keep buying many more doses than they're using.

Countries and pharmaceutical companies have kept key aspects of their vaccine purchase contracts confidential. So it's not public knowledge precisely how much vaccine each country has been bringing in. But Airfinity -- an independent, London-based analytics company — has been trying to piece this together.

First they've looked into how much COVID vaccine appears to be manufactured every month. "We've seen an extraordinary scale-up of production over the last year," says Airfinity's CEO Rasmus Bech Hansen. "We had 1.5 billion vaccines produced last month alone."

Much of that vaccine is produced by China. But of the rest, Airfinity finds that just under 60% is going to a group of wealthy countries: the United States, the United Kingdom, the European Union nations, Canada and Japan.

So then Airfinity looked at how many of these doses those wealthy countries appear to be actually using each month — and how many have been left over.

Sponsored

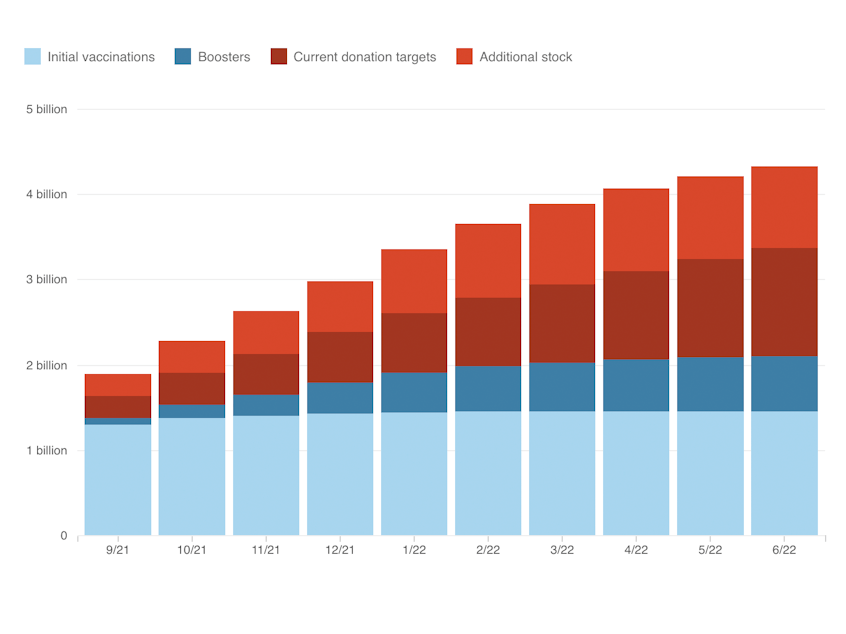

Airfinity's estimate: Depending on the country, anywhere from a third to half of the vaccines are going unused. And because this has been happening month after month, the excess has been accumulating. "We're still seeing quite a lot of stockpiling happening," says Hansen.

By year's end Airfinity projects the surplus will have reached 1.2 billion doses. And their estimate is roughly in line with projections by several other analysts.

Hansen hastens to add that largely due to recent commitments from the U.S. he projects that by December about 600 million of these excess doses will be donated to other countries — about 300 million of that coming from the U.S.

But Hansen says that could still leave another 600 million doses sitting unused in stockpiles — with nearly half of that in the U.S. and the rest in the other wealthy countries.

And he says that surplus would have been enough to meet a key goal for this year set by the World Health Organization: vaccinating at least 40% of people in lower income countries.

Sponsored

"It seems increasingly unlikely that the world will achieve that goal. We're still in a situation where only about 2.5% of the low income population has been vaccinated," he says.

It gets worse. Airfinity estimates that about 50 million doses in the rich country stockpile are on the point of expiring before they can be donated.

"It is a tragedy," he says.

Also the company's forecasts suggest the unused stockpile will keep growing well into next year — even after accounting for the additional vaccines countries will be using for boosters and extending vaccination to kids.

Hansen says this over-buying might have made sense back when there were concerns about how reliably manufacturers could keep pumping out doses. But he maintains that's no longer the case. "Once you know that you have a steady supply you don't actually need to stockpile as much."

Sponsored

Andrea Taylor of Duke University's Global Health Innovation Center says one solution is for wealthy countries to transfer portions of their monthly purchasing rights to other nations. She notes that this might require the vaccine makers to accept lower payments from those other countries. But she adds with a chuckle, "It takes only the most cursory glance at the income and earnings statements coming out from the vaccine makers to know that they can take it. They can take the hit without any problem at all."

Analysts are also pushing for more of the doses in the existing stockpiles to be shipped overseas. One of them is Rachel Silverman of the Washington think tank Center for Global Development.

"The logistics as I understand it are somewhat complicated," she says, "but do-able."

And so, she adds, the world needs to "figure out how to fix it." [Copyright 2021 NPR]