September smoke may have led to nearly 200 deaths in Washington

University of Washington researchers say nearly 200 people likely died this month from wildfire smoke in Washington state.

Their preliminary estimate is based on the known effects of breathing sooty air and daily records of air quality in September from 62 monitoring stations across the state.

Environmental economists at Stanford University calculated even higher numbers: Their unpublished estimate, shared with KUOW, found that September’s smoke would have killed nearly 300 people above the age of 65 in the Seattle-Bellevue-Tacoma area alone.

Whatever the true number, the analyses suggest that the toll of wildfire smoke can dwarf that of the fires themselves.

Only one person, a toddler who died as he and his parents attempted to flee the Cold Springs fire near Omak, is known to have died in Washington’s fires this year.

University of Washington researchers say their findings, released in a "preprint" before being peer reviewed, are only the “tip of the flame” when it comes to the human impacts of smoke: The intensely smoky air across the state would have sickened many more people than it killed.

Sponsored

“If we look at hospitalizations or emergency room visits, that will give us even larger numbers,” said lead author Yisi Liu, a Ph.D. candidate in the university’s department of environmental and occupational health sciences.

Liu, who is from China, has been studying the health impacts of traffic exhaust but jumped to this topic once thick smoke hit the Seattle area.

“I noticed that it's even worse than in many famous polluted cities in China,” she said.

Liu and her colleagues in Seattle started to feel ill themselves.

“For us, it's maybe headache and dizziness,” Liu said. “But for people with pre-existing cardiovascular or respiratory diseases, this wildfire [smoke] may be more hazardous.”

Sponsored

Deep in the lungs

Wildfire smoke is mostly water vapor, but it also contains tiny, sooty particles that can go deep in your lungs.

Scientists have long known exposure to these tiny particulates (known as PM 2.5) can quickly lead to breathing problems, heart attacks and strokes in people made vulnerable by pre-existing medical conditions.

Long-term exposure to the tiny pollutants also increases the risks of heart disease and death.

The University of Washington team looked at air quality county-by-county over the two weeks that smoke darkened Washington skies. In much of the state, PM 2.5 levels increased tenfold, while the sooty pollution in Klickitat County, near the border with Oregon, increased 80-fold.

Sponsored

When they did their analysis, the state’s air-quality disaster was ongoing, with no end in sight. So they estimated the toll that the pollution would take per week: 74 to 107 short-term deaths in Washington state from a week’s exposure to the wildfire smoke.

“It would be useful for them to put this number of deaths in context,” environmental health scientist Sarah Henderson at the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control said.

“I have no doubt that people died in Seattle because it was smoky,” Henderson said. “But when you don't present the data in a way that gives it that context, it looks alarmist, and that doesn't do us any favors.”

In a typical week, about 1,100 people die in Washington state, according to the Washington Department of Health, with heart disease and lung disease being among the top five causes of death.

Henderson said we can never attribute any individual death to smoke.

Sponsored

“When you look at their death certificate, it doesn't say, "wildfire smoke." It says, 'heart attack,' or 'respiratory failure' or any of the things that people normally die of,” she said. “What we can do is say, OK, on days when it's really smoky, about 1% more people die than on days when it isn't smoky.”

After excluding deaths from trauma, 1% more people die on wildfire smoke days, and 2% more people die the following day, than on a typical day in Washington state, according to a University of Washington and Washington Department of Ecology study published in January.

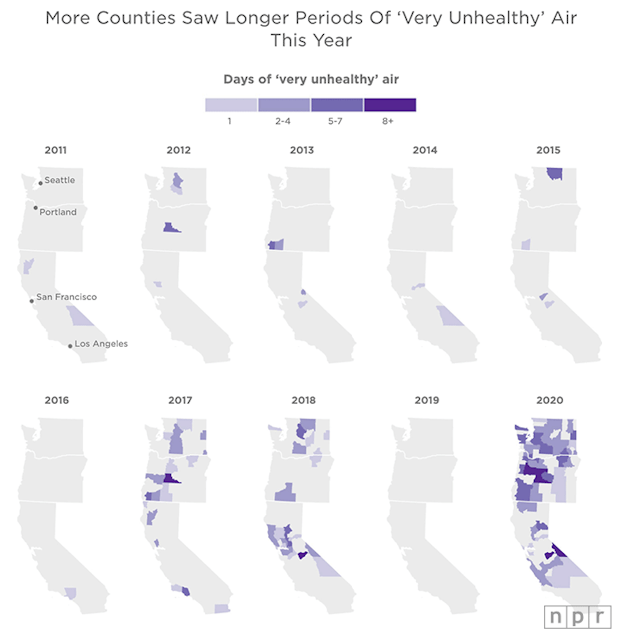

That study looked at the years 2006 to 2017, none of which were as smoky as 2020, which is already the worst year on record for wildfires on the West Coast, with a month left to go in the fire season.

Sponsored

Environmental economist Marshall Burke at Stanford University called the new work by Liu and her colleagues “a sensible initial estimate.”

Burke and his Stanford colleague Sam Heft-Neal, in an analysis self-published without peer review this month, estimate that wildfire smoke has killed 1,200 elderly people in California this year and sent 4,800 to the emergency room.

Their calculations rely on studies quantifying the link between PM2.5 exposure and deaths in Americans 65 years or older. Those calculations yield higher mortality figures for Washington state than Liu and colleagues derived.

According to unpublished estimates Burke shared with KUOW, wildfire smoke through Sept. 15 would have caused about 290 short-term deaths among the elderly in the Seattle-Bellevue-Tacoma area and about 440 in the Portland area.

“The key concept here is the number that you choose will dictate the number that you get in the end,” Henderson said.

She said if the University of Washington study had relied on studies of wildfire smoke, rather than studies of PM 2.5 more generally, their numbers would have been higher.

Sources as varied as power plants, cars, wood stoves and wildfires belch out particulate pollution.

“Wildfire smoke is extremely irritating for people who have asthma and COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease],” Henderson said.

Where there's fire, there's smoke

“I don't think we've ever had such a large population of Washington exposed for an extended period of time to such unhealthy smoke,” University of Washington emergency physician Zack Wettstein said. “One of the things we're seeing with climate change is that we're having longer wildfire seasons.”

Western wildfires are expected to worsen in coming decades as fossil-fuel use drives the world's climate farther into uncharted territory.

Wettstein said that while Seattle's air was thick with smoke in September, he treated an unusual number of stroke patients, though not respiratory patients, at the Harborview and University of Washington medical centers.

“What is striking is when you see five people who come in with really bad strokes, and they're in their 40s and 50s, you have to wonder,” Wettstein said. “This feels out of the ordinary.”

Wettstein, who took a year off from his medical studies to study the health impacts of smoke in California, said researching wildfire smoke is tough.

“It's so unpredictable, and it happens often for brief periods of time,” he said.

Wettstein credited Liu and her colleagues for getting results so quickly, by combining real-time pollution data with previous studies of the impacts of that kind of pollution.

Liu said she’d like to see government dedicate more resources to helping people protect themselves from wildfire smoke, especially in low-income communities that might have difficulty buying smoke-blocking masks and filters and are more likely to have to work outside, smoky air or no.