28% of families in Washington state can't afford basic needs, UW study finds

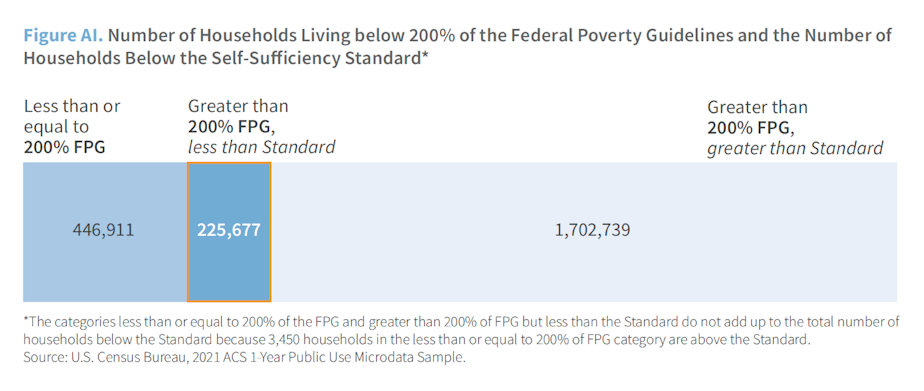

About 10% of households in Washington state meet the federal poverty threshold, but when researchers drilled into the data on what it actually takes to survive in the state, they found the number of families struggling to make ends meet is much larger.

More than 1 in 4 families in Washington can’t afford to cover their basic needs without government assistance, according to a study from the University of Washington published Monday.

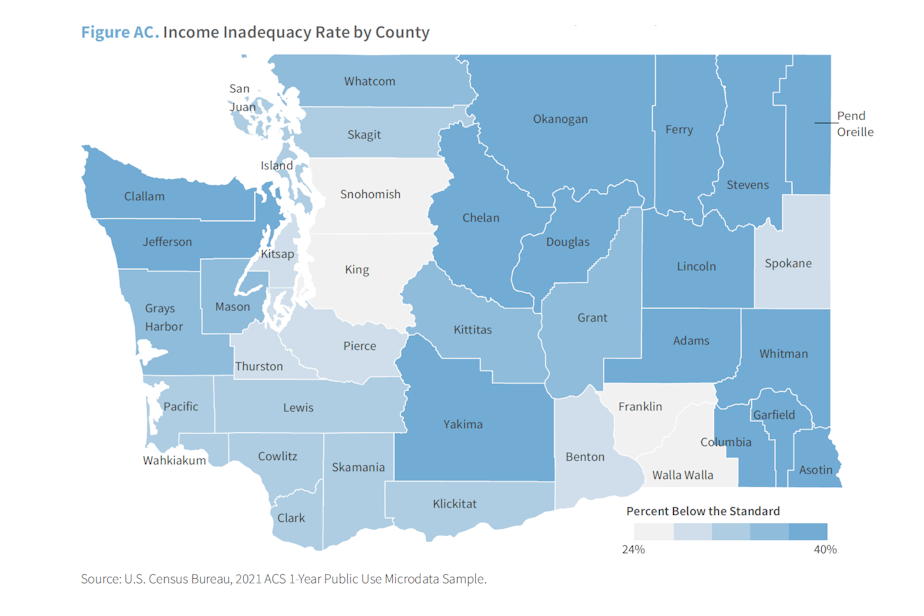

The research uses a metric called the "Self-Sufficiency Standard." It factors in the cost of housing, child care, transportation, health care, food, and other essentials by region, to provide a more accurate snapshot of economic insecurity in the state. In some counties in Eastern Washington and on the Olympic Peninsula, up to 40% of families struggle to afford those essential needs. The study's authors attribute growing economic insecurity to lasting effects from the pandemic and rising living expenses.

“We tout ourselves as being progressive and ensuring that we're taking care of everyone here,” said Anne Kucklick, co-author of the report. “When 1 in 4 of our households are not able to cover their basic needs, it really shows that there's a large issue that needs to be addressed.”

Sponsored

Kucklick hopes the research will dispel myths about families experiencing poverty in Washington. About 80% of households below the Self-Sufficiency Standard have at least one working adult and 60% have at least some college credit.

“Many of these households are working,” she said. “This is not for a lack of work effort. People are trying to cover their basic needs and they're just not able to with the earnings that are being provided by many of these jobs. And education is not paying off as it used to, particularly for households of color.”

Although increased education is still tied to economic security, the benefits of more schooling aren’t shared equally across different demographics. About half of white men in the state who don’t have a high school diploma are below the Self-Sufficiency Standard. Roughly the same percentage of women of color who have a diploma and some college credit are below the standard.

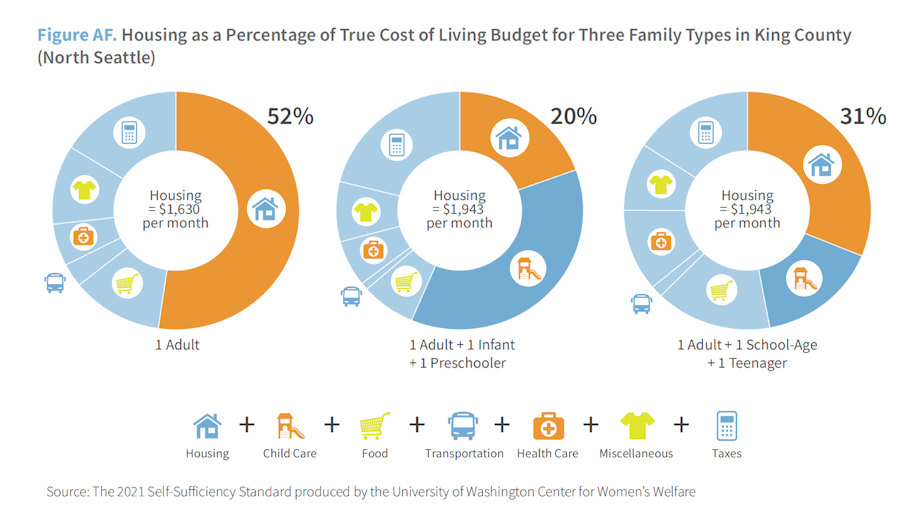

In addition to race and ethnicity, there’s another factor that can determine the likelihood that a family in Washington is economically insecure. Households with kids — particularly young children — are more likely to fall below the Self-Sufficiency Standard. Forty-seven percent of families that have at least one child under 6 years old are financially insecure, compared with 23% of households with no children.

Sponsored

“We’ve been calculating these numbers since 2000, and we find that the cost of child care alone, on average, has gone up by 171% in the last 23 years, and earnings have gone up by 60%,” Kucklick said.

According to Kucklick and her fellow researchers, two factors are driving the growing number of Washington families struggling with economic insecurity. First, the COVID-19 pandemic had a lasting financial impact. The percentage of families in Washington below the Self-Sufficiency Standard increased by 6% since 2019.

But the pandemic just exacerbated an ongoing trend. The cost of housing and other essentials has been outpacing increases in income across the state for decades. It’s a trend that extends beyond Washington’s borders. California has a slightly higher percentage of economically insecure households, while Oregon’s is slightly lower. In New York, researchers found 50% of households fall below the standard.

Sponsored

Those numbers may seem daunting, but Kucklick says there are public policy levers that can move the needle on economic insecurity. She said policies like the child tax credit and child care subsidies included in the American Rescue Plan had a meaningful impact on families struggling to make ends meet.

“What we're hoping is that it can be used as a tool with organizations across Washington, and then also with our other reports across other states, as a tool for advocacy, for minimum wage policy increase, for tax policy,” she said. “And it really can provide a better understanding of who is struggling to cover costs. It's not just people who are experiencing dire poverty.”