Lessons Learned From The Iowa Caucuses, And Danger Signs Ahead

If the Iowa caucuses were a pop quiz on how well the nation is prepared for the 2020 elections, it looks like almost everyone failed. Or at least that they need to do a lot more remedial work.

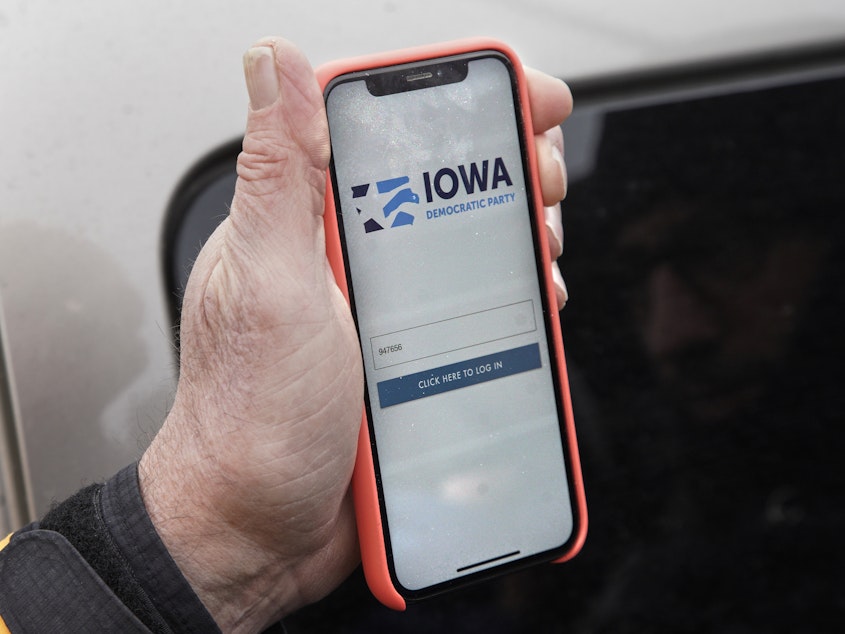

The meltdown was extensive. A smartphone app purchased by the Iowa Democratic Party for precincts to use to report caucus votes didn't work as planned. A backup hotline system also failed, leaving party officials scrambling on Tuesday to answer questions and produce results, as candidates and the public tried to figure out what was going on.

Some election watchers were not surprised.

Douglas Jones, a computer scientist at the University of Iowa, was one of many who have warned for weeks that maybe it wasn't such a good idea to introduce a new technology at such a critical time — with the eyes of the nation on the first presidential voting of 2020.

"Caucus chairs in many cases apparently were attempting to download and install the app on their phones on caucus night. That's extraordinarily difficult, to do that kind of thing under pressure," says Jones. "Downloading an app at the last minute is crazy."

Sponsored

Elesha Gayman, the Democratic Party chair in Scott County, said their attempts were complicated by measures put in place to protect the reporting system against outside attacks.

"We had a lot of our precinct captains and temporary chairs, and permanent chairs, that were trying to log in to the system, and quite frankly there were so many layers of security, they would get messed up," she said. Out of frustration, they resorted to calling a backup hotline, which was quickly overwhelmed with calls.

There were other worrisome things that occurred Monday night, which election experts see as warning signs of the kinds of problems that can emerge in the months ahead.

Secrecy Fed Unrealistic Expectations Around Results Timing

Iowa Democratic Party officials were secretive about the details of the new smartphone app and whether it had been tested in advance for possible flaws.

Sponsored

When things began to go awry, the party was vague for hours about what was causing the delay, leaving the public and campaigns confused, frustrated and even suspicious. The party had promised the new app would also mean quicker results, but instead the hours dragged on with nothing to report.

"The media is ready to go and everyone's ready to declare a winner and the candidates have their speeches and there's this sense of anticipation," says Rick Hasen, an election law expert who has just written a book — Election Meltdown: Dirty Tricks, Distrust, and the Threat to American Democracy — about all the things that could go wrong in 2020.

"If the Iowa Democratic Party had said, 'Well, it's going to be a day or two before we have results,' people's expectations would have been managed," Hasen said.

Election experts say that should be the message going forward and officials shouldn't be pressured into rushing out results that later prove to be wrong. They warn that votes could take an especially long time to count this year, in what's expected to be a high-turnout election with widespread use of mail-in ballots.

New Voting Technologies Rolled Out Too Quickly

Sponsored

While Iowa's caucuses are unique, others have also been considering the use of smartphone apps and Internet voting.

Monday's meltdown has given them pause.

On Tuesday, Nevada's Democratic Party announced that it will not be using an app like Iowa's in its Feb. 22 caucuses despite having paid tens of thousands of dollars to the developer, a company called Shadow.

But Hasen notes that there are a number of states, such as Pennsylvania, that will be using all new voting equipment this year and that could lead to breakdowns and confusion.

Some have already encountered problems.

Sponsored

A county in Pennsylvania had an election last November in which the machines showed only a handful of votes for a judicial candidate, while a recount showed that in fact he had won. Officials and vendors are working together to make sure it doesn't happen again. They also breathed a sigh of relief that the problem emerged last year, while there was still time to fix it before this year's election.

Uncertainty Fed Conspiracy Theories

It wasn't long after it became clear there was a problem in Iowa that the conspiracy theories began to fly.

"Dems rigging it in Iowa? Such a peculiar vote delay. They just can't let the People have their say!" tweeted Kayleigh McEnany, press secretary for President Trump's reelection campaign. Donald Trump Jr. alleged, without evidence, that Iowa Democrats were "fixing the results to get the candidate the Democrat Overlords in DC want."

Some Democrats also raised questions about the legitimacy of the vote, even hinting that the system had been hacked, something quickly dismissed by security officials.

Sponsored

The spread of disinformation, especially on social media, is seen as one of the most serious threats to public confidence in this year's elections. "We need to be on guard against that and really watch against disinformation and attempts to rile people up in an already very polarized environment," says Hasen.

"Teachable Moment"

Iowa caucuses are different from primaries and general elections because they're conducted by party officials, not by people who run elections as a full-time job.

But that left a serious gap. Iowa Secretary of State Paul Pate issued a release making clear that his office had "'no official role in the Iowa Caucuses." Federal authorities were in contact throughout the evening with party officials, checking to make sure there were no signs of a cyberattack.

But they deferred to the Iowa Democratic Party to tell the public what was going on. Department of Homeland Security officials also say they offered to test the new smartphone app for security flaws in advance of the caucuses, but that the Iowa Democratic Party declined.

"Was it satisfying? No. Was it frustrating? Yes," says Christopher Krebs, who runs the DHS cybersecurity agency that works on election security. But Krebs called the Iowa meltdown a "teachable moment," a stark reminder to those running elections that they need to be prepared for every contingency.

"Do you have your plan?" asks Krebs. "If something goes wrong do you know who you're going to call, what you're going to say to the political parties, what you're going to say to the press, what you are going to say to the voting public?"

Krebs says one good lesson learned from the Iowa incident is that having a paper record of votes — which the caucuses did — is key. If something happens to the technology, he says, those paper ballots are available to count and audit and to reassure the public that the results are accurate. [Copyright 2020 NPR]