On #MeToo, Americans More Divided By Party Than Gender

One year after the #MeToo movement took off, new NPR-Ipsos polls show the nation deeply divided on sexual assault and harassment, with fissures running more along party lines than gender.

Most — 69 percent — of more than 1,000 Americans surveyed, say the movement has created a climate in which offenders will now be held accountable. But more than 40 percent feel the movement has gone too far.

What exactly "too far" means wasn't defined in the surveys. But in follow-up conversations, several respondents cited a rush to judgment, the prospect of unproven accusations ruining peoples' careers or reputations, and a bandwagon effect that may prompt some to claim sexual misconduct for behavior that doesn't quite rise to that level.

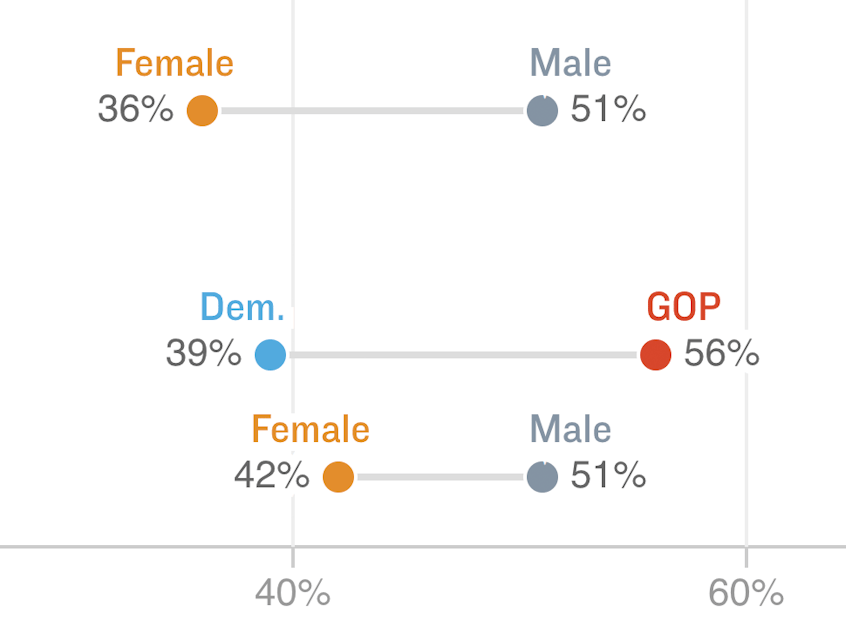

On whether alleged victims of sexual assault should get the benefit of the doubt, 85 percent of Democrats agree, compared to 67 percent of Republicans. That party gap is nearly twice the size of the gender gap.

A similar partisan divide emerges on giving the benefit of the doubt in cases of sexual harassment. That has gap widened — in the past year, mostly because of Republicans' shift in opinion.

Sponsored

For example, 53-year-old Cindy Bradshaw from Texas says she feels many allegations are exaggerated or not legitimate. "I feel like in the last year, that girls are like 'Oh yeah, me too!' " she says. "I feel like some of the girls want the sympathy and the attention. And I feel like that really, really takes away from the girls that it really happened to."

On the question of whether false accusations of sexual assault are common, the party gap is quadruple the gender gap: 77 percent of Republicans believe false accusations are common, compared to 37 percent of Democrats.

Democrat Steve Novotny from Georgia is one of the respondents siding with alleged victims, and dismissing what he sees as a myth of false accusations.

"I think that's the exception as opposed to the rule," Novotny says. "I mean I think most people wouldn't make up something just to get back at someone. They don't want to put themselves under that public scrutiny."

On the other side, Republican women like 74-year-old Carolyn Ricketts from California believe alleged victims should definitely not get the benefit of the doubt.

Sponsored

"I would be tempted — as a woman to believe a woman over a man," she says. "But, to see that justice is done, you can't do that. There's two sides to every story."

That doesn't surprise Clara Wilkins, a social psychologist at Washington University in St Louis.

"According to our research, when there's a conflict between gender and party, party wins," she says. "That's what going to drive [people's] attitudes."

Indeed, the surveys show nearly twice as many Republican women (47 percent compared to 26 percent of Democrats) worry that a man they care about will be unfairly accused of sexual assault.

Has the movement gone too far?

Sponsored

One of the most stark partisan divides is whether the #MeToo movement has gone too far. Overall, 43 percent say it has. But broken down by party, that includes three-quarters of Republicans compared to less than one quarter of Democrats. The split reflects a backlash to the #MeToo movement that's been growing since the recent controversy around now-Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, whose nomination was threatened by accusations of sexual misconduct.

President Trump has helped bolster the backlash, with recent comments like, "it's a very scary time for young men in America" because "somebody could accuse you of something and you're automatically guilty." The NPR-Ipsos surveys suggest that's resonating with his base.

"We have females that make false allegations and jumping on the 'me too' bandwagon," says Nate Jurewicz. "And it's ruined a lot of guys' lives."

Earlier this month, Jurewicz, a self-described "Christian, conservative, Republican, deplorable Trump supporter," launched a #HimToo Facebook page that drew nearly 15,000 likes in the first two weeks. It's full of slogans like: "No man is safe!" and memes mocking the #MeToo movement, such as one cartoon— showing "Jill" accusing "Jack" of pushing her down the hill, 300 years ago.

Our poll data suggest Americans are still somewhat confused about what #HimToo actually means. (It's had several different uses in recent years.) But the survey indicates that men — and Republicans especially — are paying attention. Jurewicz says the page is not meant to be partisan, but he concedes it is drawing an overwhelmingly conservative following.

Sponsored

According to the NPR surveys, Americans are also divided on whether allegations of sexual misconduct would dissuade them from voting for a political candidate. Sixty-four percent of Democrats say allegations would be a deal-breaker, while 60 percent of Republicans say they would still consider supporting the candidate.

Jurewicz goes a step further, saying even allegations proven true would not in his mind automatically disqualify a political candidate. "No one's perfect. So if something happened years and years ago, does that mean we just write that person off forever? Let the people decide if they want to vote for that person or not."

"Raising the bar too high"

On the other end of the spectrum are those disappointed that #MeToo still has so far left to go.

Nearly a third of women and Democrats say they believe allegations of sexual assault are still ignored these days. That's up slightly from last year.

Sponsored

For example, 52-year-old Texas Democrat Juan Rodriguez says he believes allegations get dismissed because people demand a level of proof that often just doesn't exist in sexual misconduct cases.

"The way things are now, I think [allegations are] just going to get brushed off," he says. "It's sad to say, but it's like they're raising the bar too high, like you've got to really prove your case. But honestly, that just gives the perpetrator the right to get away with stuff."

Debra Katz, the attorney who represented Kavanaugh's accuser, Christine Blasey Ford, says she saw it first hand. All the talk about false accusations she says is just "red meat to Trump's base."

"These talking points are being used to discredit women and to weaponize this issue of sexual harassment and sexual assault just simply for partisan gain," says Katz. "The president [is] deliberately muddying the facts to confuse people about what sexual harassment and sexual assault are by blaming victims, and in that way giving people a pass for engaging in the behavior," she says. "And it's dangerous."

Ultimately, Katz believes, the backlash will succumb to the passage of time.

"The younger generation definitely understands this issue in a way that my generation did not," she says. "They are energized, they will vote, and there's no going back."

Defining harassment

The NPR-Ipsos poll shows much more consensus among young people. For example, fewer people under 35 believe that #MeToo has gone too far, fewer say they would ever consider voting for a political candidate accused of sexual assault, and more young people say they are clear on what counts as sexual misconduct.

That stands in contrast to older Americans. After a year of intense focus on sexual misconduct, half of those surveyed say they're still unclear on what crosses the line.

Broken down by party, just over a third of Democrats say they're fuzzy on what harassment means, compared to two-thirds of Republicans.

Eric Savignano, 49, a telecommunications engineer from Pennsylvania, agrees that it's hard to define. But he takes issue with the way one of his clients has done it.

"I have to sign a piece of paper that says I have to follow all these rules, [including] you can't look at a member of the opposite sex for more than three seconds," he says. "That doesn't make any sense to me!"

California Republican Carolyn Ricketts agrees that many definitions are too broad. But she sighs, "It's hard. Some people are too sensitive."

The rest of the nation seems to be struggling for a better answer. Responses to our open-ended poll question on what constitutes sexual harassment ranged "inappropriate touch" and "demanding sexual favors" to "unwanted attention," "invitations," or "anything that makes someone uncomfortable." Many simply answered, "I don't know." [Copyright 2018 NPR]