Ruby was a typical Instagram user. Then something strange started happening…

...and she got hacked.

Ruby was a young working woman living in Seattle who enjoyed using Instagram.

“I just post photos of myself, my dog, my friends,” she said. “I’m a typical Instagram user. I just have a very special name.”

What was Ruby’s very special name? It was … Ruby.

Ruby is what’s known as an “OG username” in insta parlance. Short usernames, like Ruby, nouns like rainbow, and single letters, are coveted.

Ruby happened into this username five years ago, and once she got it, something interesting started happening … Every day, 10 to 20 new people would follow her account.

Sponsored

These were strangers, and Ruby thought they were probably shell accounts.

“They wouldn’t have many posts or they wouldn’t follow many people,” she said, “but they would have a lot of followers, or their name was Ruby something, and they would message me and say ‘I want your username.’”

Someone messaged her and asked if the username was for sale.

Then an offer: $5,000.

And another: $25,000.

Sponsored

Ruby couldn’t believe it — was @ruby really so valuable?

“I negotiated with him because I thought it was a joke, and I was like, ‘This username is worth so much, I get offers all the time,’” she said. “‘Look at all these people named Ruby that follow me. I want $100,000.’”

The man countered: $35,000.

No way, Ruby said. $85,000.

“And then he said, ‘I’ll give you $65,000, and that’s my final offer,’” Ruby said.

Sponsored

The negotiations didn’t pan out, which wasn’t too surprising.

And then a few weeks later, while she was sitting at her computer, she received a message from Instagram: an iPhone in Chicago had logged into her account at 2:08 p.m.

Ruby immediately logged in and changed her password — all within the same minute.

Three minutes later, she received the message again. This time when she logged in, she found that someone had changed her Instagram username.

She was now Ruby Done. As in, Ruby-no-longer.

Sponsored

“Just a slap in the face," Ruby said.

As she fumed over the loss of her Instagram username, it dawned on her that she was supposed to receive a phone call at 2 p.m. That call hadn’t come through.

That’s weird, she thought.

Then her text messages quit, and a message flashed on her phone: “No SIM card.”

That’s when Ruby knew how she’d been hacked. She’d been SIM swapped, which she knew about from listening to an episode of the podcast Reply All. The episode was titled, “The Snapchat Thief.”

A SIM card is the thumb-sized card in your phone that has your personal information stored on it. You can pull it out and put it in another phone.

Let’s say you lose that card; the phone company can port that information onto a new card if you can provide enough information proving that you are you.

This is where the hacking can occur: Someone can impersonate you and get your information transferred to a new card.

And when that happens, your phone is dead. Done. As in, done like Ruby Done.

SIM swappers initially focused on celebrities and on big, wealthy cryptocurrency investors, said Alison Nixon, the director of security for Flashpoint, a cyber intelligence firm. She called those wealthy investors “whales.”

“You are going to run out of whales eventually,” Nixon said. “At this point, they are just scraping the bottom of the barrel, just SIM swapping everybody they can.”

Chester Wisniewski, a cyber security researcher with the security firm Sophos, said even if you aren’t rich, or a celebrity, or the keeper of a great Insta name like Ruby, you can still be a valuable target for hackers.

“Your social capital online is worth a lot of money to a criminal,” Wisniewski said. “Most people are on edge about clicking links and open up things we’ve been warning them for years not to do.”

But send a Facebook message from someone’s account, and family and friends will likely open it up.

“You don’t have to be famous,” Wisniewski said. “You just have to be trusted and loved.”

After the hack, Ruby called the AT&T fraud department. They told her that someone walked into a kiosk at a shopping mall in Maine with a fake driver’s license, and had the employee switch Ruby’s phone number to another phone.

AT&T declined an interview request. In a statement, a spokesperson said the company aims to restore phone service quickly to victims.

Ruby’s two reports to Instagram have gone unanswered. Instagram declined a request for an interview. An emailed statement said that the company is aware of problems, and testing new security measures that will allow users to reclaim hacked accounts.

Wisniewski said not to expect answers from Instagram, which is owned by Facebook.

“The social media companies are the ones that seem to have no interest whatsoever in being responsive to their customers when these things happen,” he said. “Your bank will give you your money back and help you deal with any fraud losses, assuming that it’s not gross negligence on your behalf …

“But the social media companies you almost never hear from unless you are a movie star.” So how best to protect yourself from these hackers?

Nixon, the director of security, said that’s tricky.

“My answer kind of sucks,” she said. “There’s a lot you cannot do. And the reason why is because the fault is not on your end.”

She said she hears stories of victims who follow best practices, who made no security mistakes, whose passwords were strong.

That being said, there are things you can do to make yourself less of a target.

First, have a passcode on your cell phone account.

Second, keep your phone number as private as possible; don’t broadcast it.

Third, two-factor authentication to your cell phone is not a safe system. If hackers have access to your phone, they can receive text messages that allow them to rest passwords.

Alison Nixon said it’s best not to link your cell phone to any critical accounts. Instead, consider linking them to a Google Voice account to add a layer of security. You can also use software programs and actual hardware to authenticate your identity.

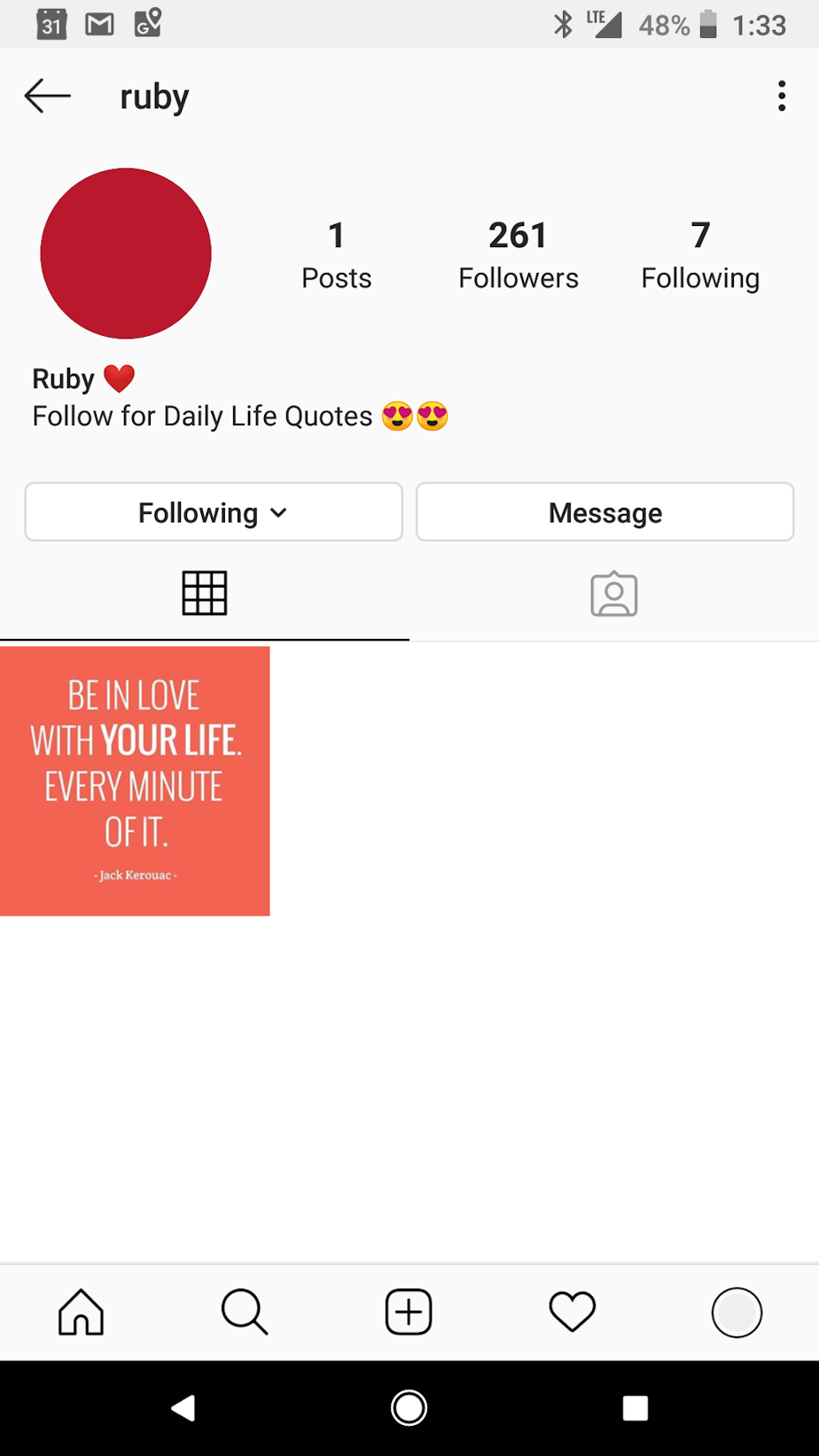

Ruby ultimately got phone service back, but not the @ruby username. The account was up for a while with an inspirational quote as the profile image. But recently the account came down.

Ruby isn’t sure she wants it back, however. It’s a great name, but it’s been trouble. And she worries she might be targeted again.

Co-hosted by Anna Boiko-Weyrauch. Edited by Gil Aegerter. Produced for the web by Isolde Raftery.