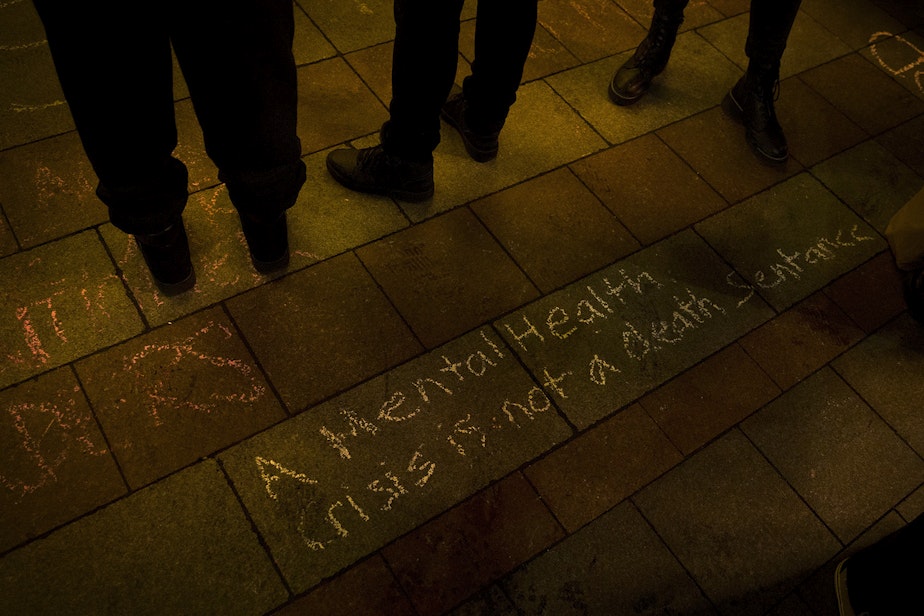

Seattle’s troubled past and present suggest a new approach to mental health

E

dward Moore, a 32-year-old sailor, was discovered, near freezing and living in a tattered tent on the shore near current day Seattle in 1854. At the time, Washington was still a territory and Seattle was a misty settlement of log cabins and wood-framed homes at the edge of the known world.

“He’d been living in his makeshift tent for months, living off raw shellfish he foraged and being cared for after a fashion by the Coast Salish people who lived nearby,” explained Josephine Ensign, a University of Washington nursing professor, and the author of “Skid Road,” which documents the history of homelessness in Seattle.

“He most likely had PTSD from a really, really bad shipwreck and maybe also potentially some traumas from his childhood back in Massachusetts,” Ensign said. “It does seem like he had schizophrenia or some type of psychosis.”

Sponsored

After having several of his frost-bitten toes amputated with an axe, Moore was taken to a doctor at Fort Steilacoom, which would later become Western State Hospital.

But when the bill came due for Moore’s care, Washington lawmakers balked. They didn’t want to set a precedent that would require the territory to care for the growing number of poor and ill sailors who were ending up on its rugged shores.

They decided Moore’s care was the responsibility of the county, not the territory, and shipped him back to Seattle by canoe. After he returned, Seattleites decided the best thing to do was to send Moore back to Massachusetts.

“Townspeople took a collection to buy him a new pair of clothes, paid a ship’s captain, and shipped him off,” Ensign said.

Sponsored

Living on the East Coast with his sister and elderly parents, without treatment for his mental illness, Moore didn’t last long.

“The cause of death was hanging,” Ensign said. “And it says, ‘Cause: Insanity.’”

Moore’s story and his death carry disturbing parallels to current-day treatment of mental illness and may also contain a message about how the region could better manage both mental illness and homelessness in the years to come. At the core of this message is the ability, or in most cases, inability, to see mental illness from the perspective of those who suffer from it.

Many of the gaps in mental health care stem from the assumptions made about the capacity of people to cope with day to day activities once they are “cured.”

Sponsored

“We have sort of the crisis management of the inpatient unit and then the outpatient treatment, which assumes that you can manage all areas of your life,” said Katherine Jonas, who researches psychosis at Stony Brook University in New York. “You can get yourself to an outpatient clinic. You can fill the prescription and remember to take them. And then there's nothing in between.”

L

ew Middleton lived in a state of turmoil for years because he heard and obeyed the many voices in his head. The voices drove Middleton into the forests of Washington state, where he lived while they reinforced his delusions.

“What I noticed was the more I collectively listened to them and the more I thought about maybe people chasing me, the more it became people chasing me,” he said.

Sponsored

One night, Middleton ran into an ex-girlfriend. He showed her the bite marks he had on his arm from a fight he’d been in, and she convinced him to go to the hospital, where he was admitted to Harborview Medical Center, one of the only hospitals in the Seattle area with a specific unit for psychiatric emergencies.

Middleton thought he’d been abducted and the anti-psychotic medicine he was prescribed was poison. But he took it and he began to notice a change.

“The voices didn't go away completely," he said. "It just kind of brought it down to the point of where they weren't so loud."

RELATED: 50 years ago, many psychiatric hospitals closed. Did that cause today's mental health crisis?

The antipsychotics that Middleton was prescribed in the 1990s hadn’t changed much since they came out in the 1950s and there have been few game-changing breakthroughs in those medications in the 30 years since.

Sponsored

“I work toward de-prescribing because people come out of the hospital with tons of medications, over-prescribed, really just kind of shells of people when they come out,” explained Alix Van Hollebeke, the head of nursing at Seattle’s Downtown Emergency Center, a nonprofit near Harborview that provides shelter, housing, and medical care to people with complex cases of mental illness and substance abuse.

“We want to get to the point where they get to live their life, even if it's weird and different and we don't understand what it's like, but they get to live their life as they want to live it. With maybe a little bit more sparkle than the rest of us,” Van Hollebeke said.

While the antipsychotics helped lower the voices Middleton heard, they did not silence those voices. They also caused side effects such as facial tics and other involuntary movements. Other meds seemed to make the voices louder.

RELATED: His mom worried he’d wind up dead. But getting him committed was nearly impossible

But the treatment and care gave Middleton the ability to separate from the voices and helped him understand they were a part of him that he could reason with and learn to live with.

“It's almost like I was playing this role like, almost like a movie, a role where I was believing everything that was going on and as soon as I tested it, the reality came through,” Middleton said. “There was nobody out there chasing me.”

Middleton went on to work at the Downtown Emergency Center and became the longest served certified peer counselor in Washington state history. The center now has a drop-in center named after him.

While some people who suffer from mental illness are able to gain stability through a combination of care and recovery, others require ongoing care that is difficult to find in the current mental health system.

D

onald is a psychiatrist who dealt for years with his son Eli going through “the churn,” spending time in psychiatric hospitals, emergency rooms, living on the street, and seeking relief through alcohol and drugs.

Donald and his wife, who asked that their last name not be used to protect his son’s identity, reached a critical moment when their son was about to be arrested and he turned to his parents and asked, with a look of terror in his eyes, “Please, can’t I stay with you?”

RELATED: A boy named Adam: When psychosis spills onto Seattle streets

They could not turn him down. Donald and his wife now provide their son with 24-hour care. Their lives revolve around Eli’s daily needs for routine and consistency.

They avoid sarcasm and innuendo, which they have found lend to Eli’s paranoia and can erupt into psychosis.

“How do I help him mitigate the terror he's experiencing?” Donald asked. “The terror is terror, whether it's internally induced or whether it's externally induced, it's terror. And it's in the eyes, his eyes.”

The process of living with Eli made Donald recognize aspects of mental health care that potentially contributed to psychosis and delusion, rather than offering relief and stability. For example, not being able to sleep in a hospital because a roommate is yelling, or being overdosed on medications, then released without assistance and suffering a fall.

At the core of this frustration with his own field of psychiatry was the mistaken attitude he described as “doctors know best.” Donald did not see a genuine curiosity about the way people in psychosis were experiencing the world. He realized that mental health care, as with the “care” offered to Edward Moore on the shores of Seattle 170 years ago, was based not on the needs of the people who are sick, but on what is expedient for the rest of us.

“The quickest way is to do what we've done for centuries, which is to lock people away unseen and to make people invisible and less disruptive so that's what we do,” he said.

RELATED: Who was Lillian Massey? A journey to Northern State psychiatric hospital

One of the things that offers Donald hope is the compassion he sees in his son Eli when he encounters other people in mental distress. The first thing he thinks of when he sees someone in pain is not how he can change or fix them.

“Most people, if they can calm their minds down, and that takes time, it'll be the same for them, all of us,” Donald said. “It doesn't take a lot of know-how to offer somebody or ask them a question. What can I do to help you?”

To listen to the full episode of “Lost Patients,” tap the link above.

Looking for mental health resources? KUOW compiled an "Acute mental health resource guide" that can help.