Stop The Presses! Newspapers Affect Us, Often In Ways We Don't Realize

"Fake news" is a phrase that may seem specific to our particular moment and time in American history.

But Columbia University Professor Andie Tucher says fake news is deeply rooted in American journalism.

In 1690, British officials forced the first newspaper in North America to shut down after it fabricated information. Nineteenth-century newspapers often didn't agree on basic facts. In covering a lurid murder in 1836, two major papers in New York City offered wildly differing perspectives on the case.

"They both looked at the same crime and had entirely different interpretations based on what they thought their readers would prefer to hear," says Tucher, who researches the history of fake news. Different newspapers had different audiences, so journalists catered to the tastes and sympathies of their particular readerships.

The debate over this approach continues across the media landscape today. And it often masks a larger question that persists in American journalism: Should reporters think of their readers and listeners as consumers, or as citizens?

Sponsored

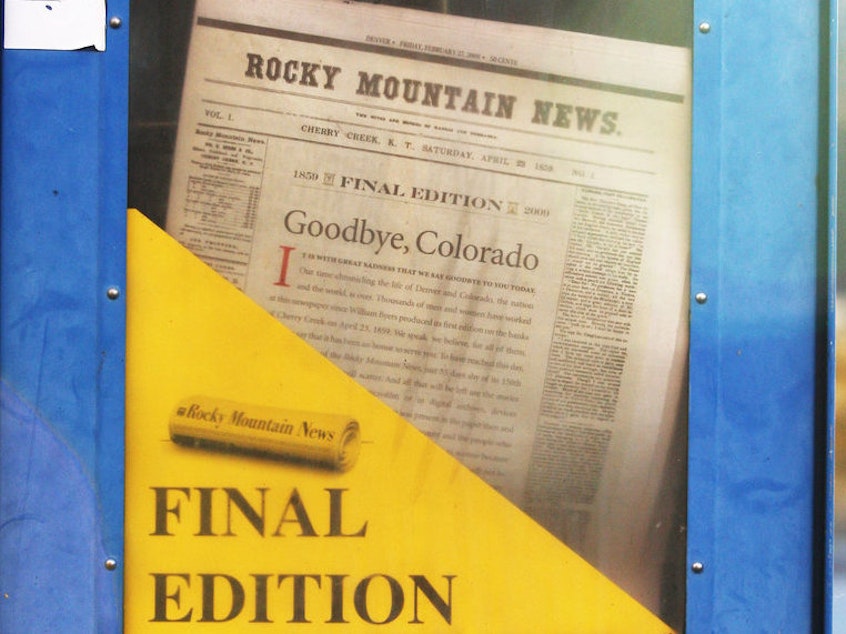

This week on Hidden Brain, we explore this tension at the heart of journalism. And we'll consider another way that the consumer model of news affects the quality of information that we can access: There are plenty of ways today to pay little—or nothing—to read the news. There are free blogs. There's Facebook and Twitter. As a result, millions of Americans have decided they don't need to subscribe to a local newspaper.

But new research suggests this strategy may have costs in the long run. That's because newspapers are not like most things we buy. If you decide not to buy a watch or a cappuccino, you save money. But if you decide not to pay for a police department, you might save money in the short run, but end up paying more in the long run. We ask: when nobody wants to pay for the press, does someone ultimately foot the bill?

Additional Resources

Andie Tucher writes about the sensationalist 19th-century press in Froth and Scum: Truth, Beauty, Goodness, and the Ax Murder in America's First Mass Medium.

"Financing Dies in Darkness? The Impact of Newspaper Closures on Public Finance"by Paul Gao, Chang Lee, and Dermot Murphy, forthcoming in the Journal of Financial Economics

Sponsored

"The Effect of Newspaper Entry and Exit on Electoral Politics" by Matthew Gentzkow, Jesse M. Shapiro, and Michael Sinkinson in American Economic Review

"The Afterlife of Electronics" series by I-News [Copyright 2020 NPR]