More than 60,000 workers shut down Seattle a century ago

If you were in Seattle in 1919 today, something might have seemed strange. The streetcars weren’t running, and the newspaper boys were nowhere around.

This week marks the one hundred year anniversary of the Seattle General Strike when the city shut down for five days, as more than 60,000 workers from over 100 unions stopped going to their jobs.

Many businesses shut their doors, as non-unionized Seattleites stayed home too, because they couldn’t get to work.

“Nothing moved but the tide,” striking worker Earl George told retired sociology professor Rob Rosenthal, who recorded oral histories of the strike when he was a graduate student in 1977.

George was one of the few black workers who joined the strike. (The movement did have its contradictions; People of color were excluded from most unions then.)

The unions stepped in to run the city. “They set up giant kitchens, they brought in food, they patrolled the streets,” Rosenthal said.

Sponsored

Cooked meals were especially important because single working people often lived in rooming houses or residential hotels akin to today’s “apodments,” historian and director of the Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project, James Gregory said.

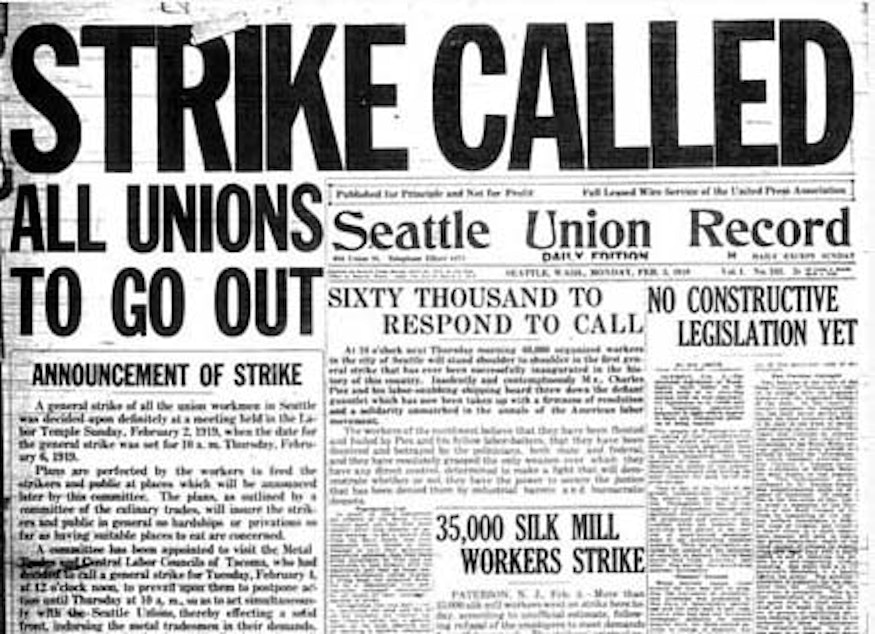

“Tiny little rooms with no plumbing in the room and no way to prepare food,” he said. A union paper declared on its front page, “LABOR WILL FEED THE PEOPLE.”

Unionized hospitality workers set up food halls across town, Gregory said.

“There were plenty of cops around, every place you went there were cops on the corners and cops tramping around on their horses,” one man by the pseudonym D.F. Cutler told Rosenthal in an interview. “Lots of people were on the streets because lots of people weren’t working. Nobody was working!”

Workers back then had some of the same struggles as us, like wages and working conditions.

Sponsored

They had something else too, Rosenthal said: a sense that they had to stick together.

“We are more isolated, far more isolated, than in the days when people lived in working class communities and went to their union hall for dinner,” he said, “They did things that over and over that said to them, ‘These are your brothers and sisters, and we have a common fate.’”

The General Strike started when the shipbuilders union went on strike to get pay raises they’d been promised following the end of World War I. Then the other unions – including the tiny hotel maids’ union, which back then boasted of a dozen members – voted one by one to stay home in solidarity, Gregory said.

The shipbuilders never got the raises they were fighting for.

“Very few people who participated thought of it as a failure,” Gregory said. “They thought of it as a grand gesture that the unions had pulled off magnificently.” Not only had they shut down the city and kept the essential services running, it was entirely peaceful. No one even got arrested.

Sponsored

Seattle exploded in headlines all over the world, sending a message that emboldened other workers and put bosses on notice.

“It had put the fear of God into employers that people in Seattle were going to stick together and fight back if they were attacked, rather than individually accept a worse deal, which is what most people have to do most of the time in the United States today.”

The strike showed a vision of how workers could control their lives and an entire city.

This week, events across the city are commemorating the anniversary.