How the arts can be Seattle schools’ stealth weapons in the fight for racial equity

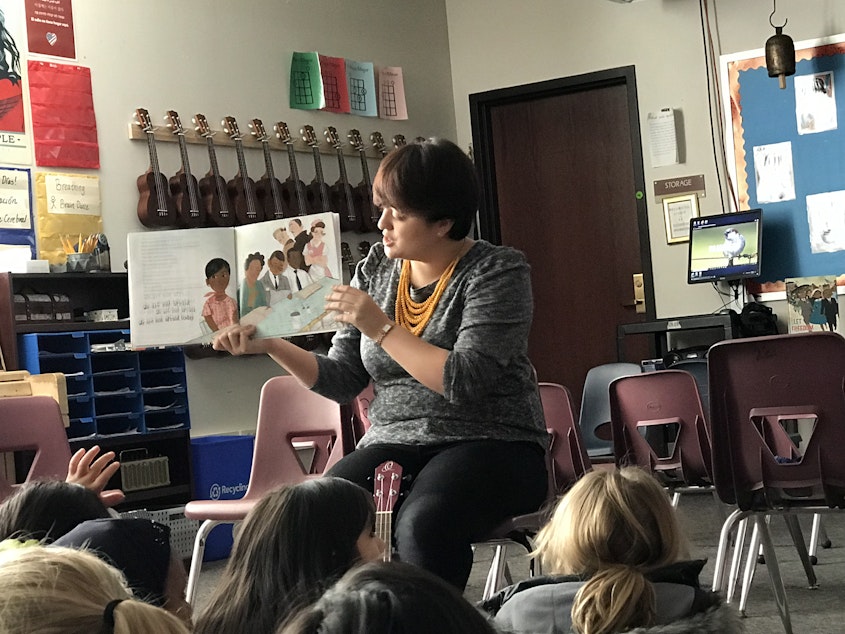

On a sunny December morning, two dozen first graders file into Jessica Staire’s classroom at Concord International School in Seattle’s South Park neighborhood. Staire picks up a ukulele, counts to three in Spanish, then leads her class in a peppy song that involves a lot of handshakes and hugs.

“Buenos dias, Buenos dias!” the six year olds warble as they circle around each other.

Concord students get the usual daily dose of math, science and reading. But Concord’s curriculum also places a heavy emphasis on the arts. They're incorporated into basic classroom lessons as well as in specialized classes like the one Staire teaches.

Advocates say this kind of arts programming is one way to achieve racial equity outcomes in schools that have historically struggled to help kids of color succeed. For that reason, Concord is a model for what all Seattle public schools will offer students in the next decade or so.

Three years ago, Concord began to implement a Seattle Public Schools initiative called Creative Advantage. The program is designed to create a district-wide, coordinated K-12 arts curriculum and to embed certified arts instructors in every building. Officials are rolling out Creative Advantage region by region, starting in south and central Seattle.

A study revealing areas of the city with less arts programming is driving the effort, says Gail Sehlhorst, the District’s Visual and Performing Arts manager.

Sponsored

“We’re rooted in racial equity," Sehlhorst says. "We lift up and invest in communities in order to make sure that everybody’s getting the same access.”

In wealthier parts of the city, many families can afford private, after-school arts lessons. But at schools like Concord International, where more than 70 percent of the families live below the city’s median income level, private arts classes would be a luxury. The school provides free hot breakfasts daily.

Almost a third of South Park’s population self identifies at Latino; many families speak English as a second language, if they speak it at all. This is exactly the kind of school the Creative Advantage was designed to reach, according to Sehlhorst.

But Selhorst and her colleagues believe infusing art into the curriculum offers more than art for arts’ sake.

Sponsored

“We talk about 21st century capacities,” she explains. “Businesses and colleges are looking for creativity, collaboration, perseverance. This is what the arts intentionally foster.”

Advocates point to research that shows participation in the arts not only helps develop problem-solving skills and creative thinking; it may help keep youth engaged in school. That’s a big issue in a neighborhood like South Park.

According to national surveys, Latino students have the highest high school dropout rate in the country. If elementary schools like Concord can get students interested in the arts, they may stay involved through high school.

Much of the push to launch the Creative Advantage program came from the city’s cultural community, but its implementation got a boost when the state of Washington adopted baseline standards for arts learning, first in 1993, then again in 2014. Those requirements were part of a broader set of benchmarks for every core subject.

Sponsored

But while the state mandates arts learning standards, it doesn’t provide Seattle Public Schools with the money to fund arts classes. The school district provides some money to help implement Creative Advantage; other funds come from the City of Seattle through its Office of Arts and Culture (OAC), and other grants. The mandate and funding are centralized, but each school develops its unique curriculum.

At Concord, for example, a Spanish language immersion school, core classes including music are taught mainly in Spanish. Staire infuses phonics or other language skills into her lessons to support whatever the classroom teachers are focused on.

This year the entire school is learning the classic civil rights anthem “We Shall Overcome.” They’ll perform it as a group in January at a celebration of the late Martin Luther King Jr.’s life and legacy.

The preparation for the performance goes beyond the song itself.

Sponsored

“This isn’t an isolated event, but more of a journey,” Staire says. She tries to connect the history that gave rise to the song to life in contemporary South Park. “People struggle with hatred, people struggle against prejudice. My students are bringing in stories that happen with their own lives.”

Staire's decision to meld social justice lessons with her music curriculum is a model for other arts educators, says Tina LaPadula of Seattle's Office of Arts and Culture. She works with the school district to implement the Creative Advantage program.

"The arts are the way to foster the radical imagination that’s required to make transformative change,” LaPadula says.

Staire says the opportunity to fuse music classes with social activism is what prompted her to take her job at Concord. It's what keeps her excited to come to school everyday.

“Teachers are hungry for having more culturally responsive teaching practices,” Staire says. “That’s why I wanted to be here. It’s not perfect, but we’re doing it and can keep fighting to make sure it gets better.”