Did Seattle’s Democracy Vouchers combat 'big money' in August's mayoral primary?

Seattle's democracy voucher program is being touted as a national model for campaign financing in articles and books, and even in Congress this year, where a version made its way into the Democrat's big voting reform bill HR1.

But the results for the 2021 August mayoral primary — which is the first time vouchers have ever been used in a Seattle mayor’s race — were mixed.

So far, the program is only in Seattle. All residents are issued four $25 vouchers that they can donate to any candidate who qualifies for the program.

The original concept, proposed by Harvard Law professor Lawrence Lessig, was to find a way to challenge the pernicious influence of money in politics. When Seattle's Democracy Voucher program got on the ballot as a part of a voter initiative, and was being debated back in 2015, then City Councilmember Mike O'Brien sold the concept as an antidote to the flood of campaign cash, where “big wealthy corporate campaign donors are pushing regular people out of the process."

Voters agreed with that sentiment and approved the initiative, which has been used in some races since 2017.

But 2021 represents a major test of the program’s promise. This year, for the first time, vouchers are being used in a Seattle mayoral race.

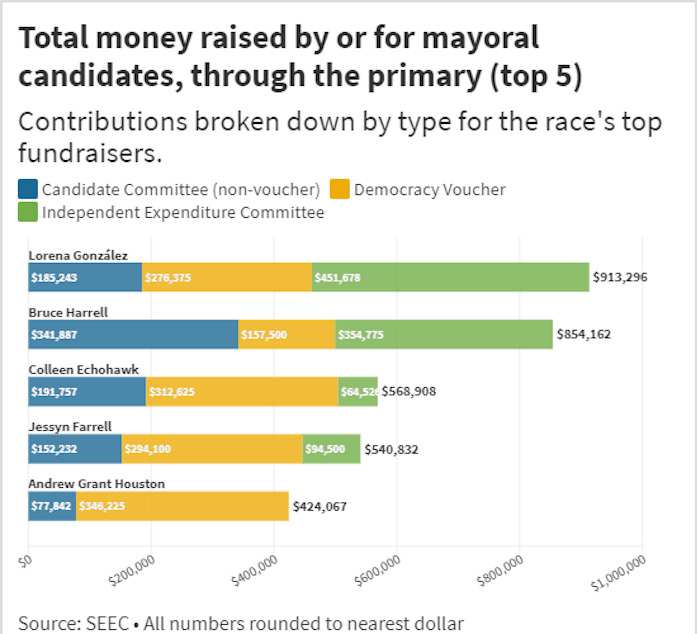

Heading into the primary, five candidates qualified for the vouchers, including the top two vote getters, Council President Lorena González, and former Councilmember Bruce Harrell. Combined, the two candidates received hundreds of thousands of dollars to spend on advertising through direct mail, digital, or cable TV. Such ads are thought to be key in this odd-year summer primary election; when voter participation tends to be lackluster, particularly after a major presidential election.

Sponsored

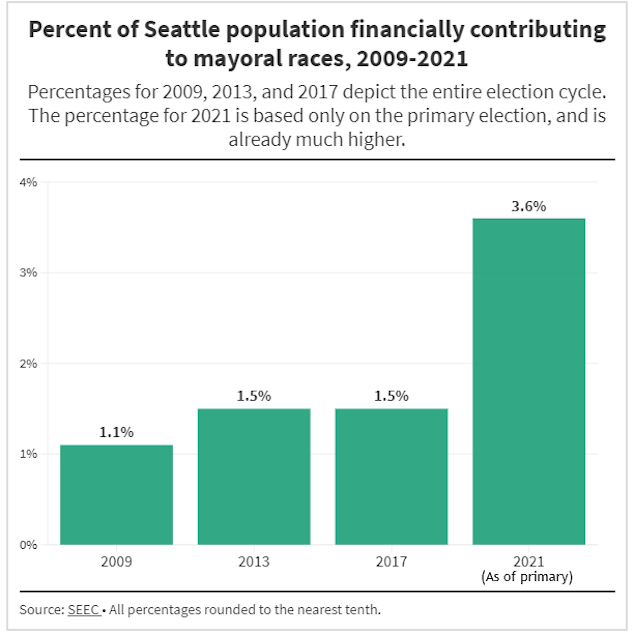

Kristin Eberhard, a researcher with the Seattle think tank Sightline, which helped draft the original Democracy Voucher proposal, said before vouchers, donors to political campaigns mostly lived in Seattle's wealthier and whiter enclaves. Thanks to vouchers, the city now has the biggest, most diverse donor pool in the entire country, with around 7% of residents participating in 2019.

“People who are under 40, people with incomes under $50,000, and people of color are now participating,” she said.

And Seattle's Ethics and Elections Commission is working to further broaden participation in 2021.

Sponsored

PAC money

Voucher enthusiasts argue that breadth of support means candidates can now spend less time buttering up wealthy donors and more time speaking with everyday voters to try and earn their votes, and their Democracy Vouchers.

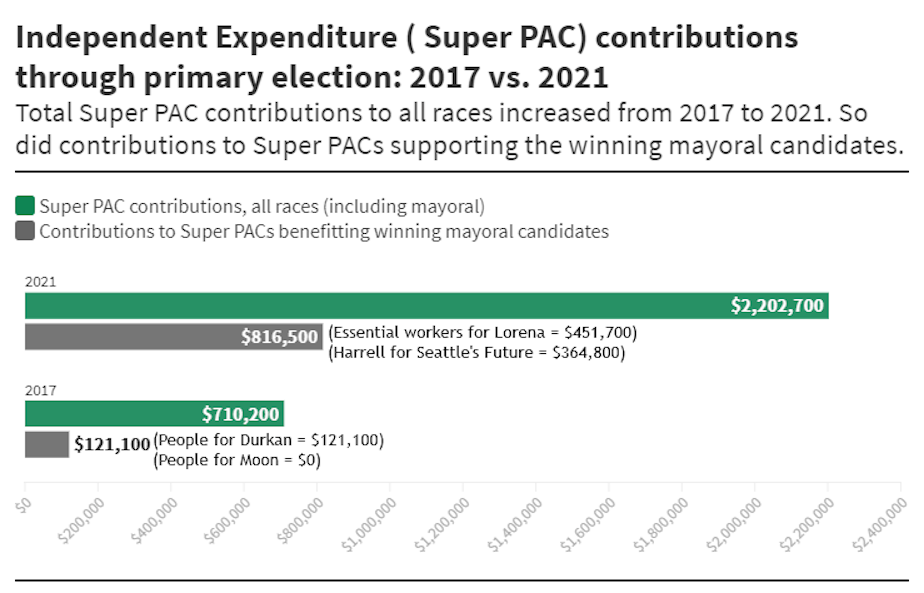

The program also sets limits on how much individuals can give to participating campaigns. But there’s a giant loophole, often linked to the U.S. Supreme Court's Citizens’ United decision.

“Independent expenditures” now flood in through so-called “Super PACS,” which are political action committees that are free to raise as much money as they want to spend independently, outside of the campaigns.

Total PAC money raised for all primary races this year more than tripled compared to 2017.

Sponsored

But the flood of outside cash was even more dramatic in the mayor's race. If you just look at the two leading PACs that supported the two primary winners this year, they raised nearly seven times more money than their counterparts in the last election.

A real estate executive and his spouse made the top two donations to the "Bruce Harrell for Seattle's Future" PAC for a total of around $100,000 dollars, and that PAC took in over $350,000.

Even more outside money (over $450,000) poured in to support Lorena González though the Unite Here labor union's PAC. Most of that money — around two thirds — came from outside the state of Washington.

Have democracy vouchers changed things?

Sponsored

But professor Jennifer Heerwig of Stony Brook University, who studies Seattle’s Democracy Voucher program, argues there's not much the city can do to stop PAC spending, and it could be worse.

“If you don't have a public financing system, what you have is outside spending, and candidates who are relying on wealthy donors,” she said.

Another plus to the Seattle voucher system: Public financing also gives a shot to candidates who have little chance of raising hundreds of thousands of dollars in other ways.

Mayoral candidate and architect Andrew Grant Houston, who reported a net worth of zero dollars, was the leading voucher recipient in this year's mayoral race.

“Someone like Andrew Houston really needs democracy vouchers, from everyday voters, everyday people in order to run,” said his campaign manager, Kelsey Hamlin.

Sponsored

But in the end, it's not clear how much democracy vouchers have really changed things.

Houston, the candidate who redeemed the most democracy vouchers, received less than 3% of the vote.

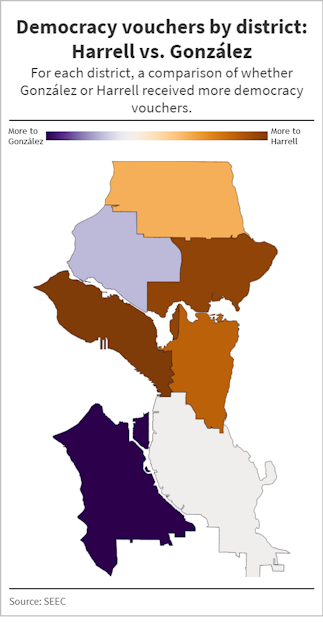

Meanwhile, the candidates who performed best at the polls, Harrell and González, redeemed the smallest number of democracy vouchers among the five candidates who used them.

If you add it all up, those two candidates with the most money and institutional support behind them are moving on to the general election, just like the last election in 2017 before mayoral candidates were allowed to use democracy vouchers.

Gracie Todd is a Roy Howard Investigative Fellow at KUOW.