Does playing soccer on artificial turf increase cancer risk, especially in kids?

Longtime University of Washington goalies coach Amy Griffin is not an activist by nature. But 15 years ago, she identified what she believed was a trend that she couldn’t ignore in good conscience — young goalies being diagnosed with blood cancer.

It started when she ran into two of her former goalkeepers at University Village, an outdoor mall in northeast Seattle. The two young women had grown up playing soccer in the same Seattle neighborhoods, on the same fields. When Griffin saw them at University Village, they had another thing in common: Both were bald from undergoing chemotherapy treatment for lymphoma.

After working with goalkeepers for decades (and playing in goal for the U.S. Women’s National Team), Griffin recognizes certain personality traits particular to goalies. Being a goaltender, especially at a high level, requires relentless optimism in the face of inevitable heartache: You can make spectacular saves, but it’s the one mistake people remember.

That day at University Village, Griffin saw that goalie attitude — unrelenting optimism and a sense of common fate — in her two former players. They saw their diagnoses as an ironic twist that was related somehow to their role on the field. Typical goalkeepers, they said, shaking their heads and smiling.

But also, “Why us?”

Sponsored

“One of them said, ‘I wonder if it's the stuff in the field,” Griffin recalled. “I wonder if it’s those little black dots, because we're eating them, we get them in our eyes, we get them in our abrasions.”

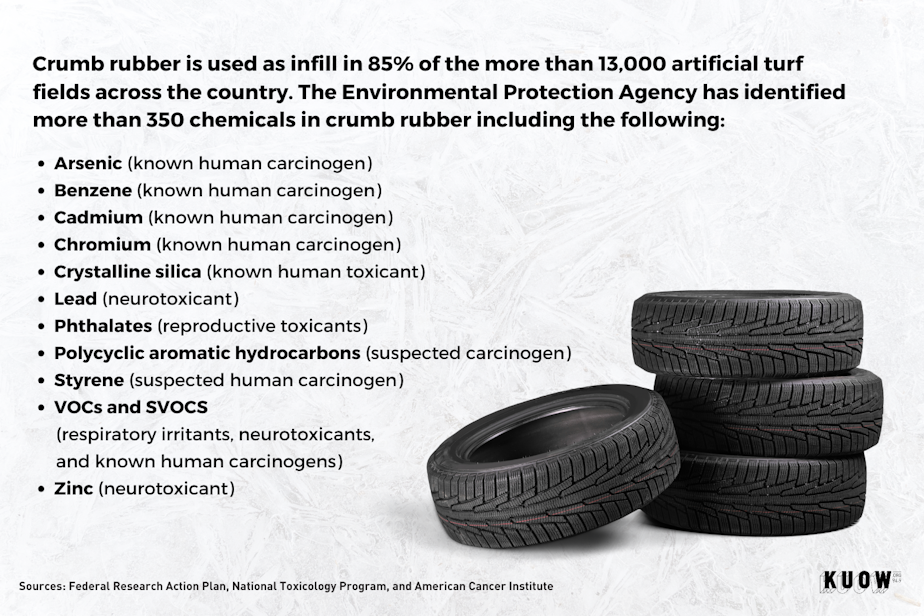

Those little black dots are the crumb rubber used as infill on more than 13,000 playing and practice fields across the U.S. Each of those fields uses 20,000 to 40,000 shredded waste tires to provide cushioning and traction. While waste tires are heavily regulated because they contain known carcinogens and heavy metals, when those same tires are chopped up and put on playing fields, they are unregulated.

For more than a decade, parents, coaches, and players have worried that the crushed-up tires pose health risks. Studies to date, both in the U.S. and Europe, have revealed extensive toxic chemicals within crumb rubber, but most conclude the level of exposure people have when playing or practicing on artificial turf is too low to put them in danger.

Meanwhile, Griffin’s list of former goalies and other athletes with cancer continues to grow. The list now includes close to 300 people, more than half of whom have a form of blood cancer.

1 min

Amelia Ye, a 10-year-old goalie, practices on crumb rubber in Seattle.

1 min

Amelia Ye, a 10-year-old goalie, practices on crumb rubber in Seattle.

Chance or cancer cluster?

Eight years ago, when the list included 53 people, Washington state looked into whether the list constituted a “cancer cluster” that warranted additional investigation. The state concluded that “exposures from crumb rubber are very low and will not cause cancer among soccer players.”

RELATED: Recycled rubber in artificial turf doesn't appear to cause cancer, state says

The state’s results, released in 2017, were publicized by multiple news outlets, including KUOW, as evidence that crumb rubber fields were safe for kids and didn’t cause cancer. But the report and its conclusions came under immediate criticism from some of the nation’s top epidemiologists and toxicologists.

“This language represents false reassurance based on faulty logic and methodology,” wrote Richard Clapp, professor emeritus at Boston University of Public Health, and David Brown, a public health toxicologist and former deputy director of the Public Health Practice Group at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta.

Sponsored

Clapp, who helped set up the Massachusetts Cancer Registry in the 80s, has been at the forefront of identifying cancer clusters for the last 40 years. He said the Washington state study was flawed in terms of its assumptions, parameters and methodology.

Clapp Brown Letter March 10 2017

Full letter from Richard Clapp, an epidemiologist and professor emeritus at Boston University School of Public Health, and David Brown, a toxicologist and director of Public Health Toxicology for Environment and Human Health, in response to a 2017 report on crumb rubber infill by the Washington State Department of Health.

“It struck me as not very thoughtful and not very complete,” he said. “I thought, for a state health department, they shouldn’t be relying on it and they shouldn’t be drawing conclusions from it.”

In particular, Clapp and Brown were disturbed by the lack of focus on soccer goalkeepers, who make up almost half of Griffin’s list even though they are only a small percentage of each soccer squad.

Washington’s Department of Health “makes unrealistic assumptions about the total number of goalkeepers in the population, thus discarding a potentially important risk factor using faulty logic,” Clapp and Brown wrote.

After criticism from Clapp and Brown and others, the state report was revised. The new introduction reads, “Our investigation was not designed to determine if soccer players in general were at increased risk of cancer due to exposures from crumb rubber in artificial turf.”

Although this revision went largely unreported by the press, at least one researcher took notice. Rachel Massey, a senior research associate at the Lowell Center for Sustainable Production in Massachusetts, focused on the original and revised Department of Health study as part of her dissertation.

At its core, she said, the state study was flawed. It was based on the assumption that Griffin’s list included everyone who played on crumb rubber fields and then developed cancer.

Griffin’s list “should have been a starting point, not a study finding,” Massey wrote. “That core calculation was just so misleading.”

Sponsored

Athletes with cancer who played on crumb rubber turf

(Having trouble seeing the graphic above? Hit refresh on your browser!)

Why goalies?

A few years ago, a longtime soccer player contacted Griffin after his first experience playing goal on crumb rubber turf. He had played in the field for 20 years, but after suffering an injury and being relegated to “mind the net,” his wife noticed a change. Black dots were everywhere. They were all over the house. They were in the shower. They were in his shoes, in the car. Wherever her goalie husband had been, crumb rubber particles were left in his wake.

Sponsored

“Goalkeepers’ relationship with that crumb rubber that’s on the field is much, much deeper than the relationship with an average field player,” Griffin said.

After a successful playing career that included five years with the U.S. National Team and a World Cup title in 1991, Griffin has become one of the top goalie coaches in the nation. She worked with goalkeepers for 24 years at the University of Washington.

Among her players was Hope Solo, who went on to play for 16 years in goal with the U.S. National Team and won the World Cup and two Olympic gold medals. Griffin was the goalkeeper coach for the U20 Youth National Team that won the World Cup in 2014. She is the executive director of the OL Reign Academy, which works with girls from the ages of 9 to 19, and head coach of the U.S. Women’s Deaf National Team, which won the world championship in 2016 and 2023 and the 2021 Deaflympics in Brazil.

Training for goalies is all about building reflexes and strength through repetition. So, while the rest of the team is running, passing, and kicking, goalies are repeatedly diving for balls, making saves, hitting the turf and getting back up. That leads to a lot of direct contact with tire crumb rubber.

One of Griffin’s concerns about much of the research done on crumb rubber is that samples used to determine exposure are typically collected five feet above the surface, where researchers assume soccer players and other athletes will be breathing when they are on the field.

But goalkeepers, especially during practice, are right at ground level much of the time, knocking up crumb rubber with their arms and legs, breathing hard, and getting their faces on the turf.

Griffin has helped goalies get the crumbs out of their eyes, so they don’t have to take off their gloves.

“You get them in your mouth,” she said. “You get them in your abrasions, and they probably get through your pores on a hot day.”

“There are four ways you can ingest toxic chemicals, and those are all four of them.”

Sponsored

When teenagers get cancer

Jean Bryant had known Amy Griffin for years. Their kids were around the same age and attended preschool together in Seattle. She had heard Griffin ponder the sudden increase in cancer among goaltenders and hadn’t thought much about it. Then the issue became all too real and personal. Bryant’s son Jack, who had played goal since he was in kindergarten, was diagnosed with a rare type of Hodgkin’s lymphoma, a form of blood cancer. He was 13 years old.

When she found out about the diagnosis, one of the first things Bryant did was contact Griffin.

“Hey, another goalkeeper for your list,” she told her.

While helping her son through treatment for a unique and largely unstudied form of lymphoma, Bryant took on the task of helping Griffin organize her growing list. She took Griffin’s notes, sticky pads, and stories and created a survey so that anyone who contacted Griffin could be directed to answer a series of questions that would add to the growing data set.

Bryant also went to work as a fundraiser at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle. Friends who knew about her son’s diagnosis and treatment asked, “Why?” Why work in an area where she was constantly dealing with and thinking about cancer? After everything she and her family had been through, why lean in?

“I’ve always been one that’s tried to turn grief or things that you can’t control into purpose,” Bryant said. “It gives me some hope, some healing.”

Jack played in goal on artificial turf from the time he was 5 — first for a club team, then for a neighborhood team, and then for his middle school.

“He’d come home with scraped knees almost every game,” Bryant said.

Despite her work with Griffin, Bryant isn’t convinced her son’s lymphoma was caused by his exposure to crumb rubber.

“It’s extremely difficult to diagnose the cause of cancer,” she said. “But I just know there are toxins on the turf field, so whether it caused his or not, I don’t have any doubt that it does play a role.”

Jack Bryant is now 22 and pursuing a doctorate in bioengineering in California. He has been through two rounds of chemotherapy, radiation, had his spleen removed, and received a bone marrow transplant. When he was recently diagnosed with cancer for a fourth time, they decided to hold off on treatment for the time being, in hopes that the cancer would remain slow growing.

“It’s hard to witness that as a parent,” Bryant said. “Because you would do anything to change places with them. So, he hasn’t had a normal kid’s life. He has been through a lot.”

Wrong answer, right time

B

y the early 1990s, scrap tires were a serious problem in the U.S. An Environmental Protection Agency report in 1991 estimated that 242 million scrap tires were generated every year, and two billion tires had accumulated in stockpiles or uncontrolled tire dumps.

But in the early 2000s, a solution to the “tire problem” presented itself — by shredding waste tires and spreading the resulting particles on artificial turf fields, on-field injuries could be reduced while tire waste was diverted from landfills. By 2007, 300 million pounds of rubber were being diverted from landfills to use on playing fields.

Promoters of crumb rubber fields point out that artificial turf saves water, reduces the need for pesticides and fertilizers, and eliminates emissions from mowing. They market turf fields as consistent, year-round, all-weather playing surfaces that don't require recovery time like natural grass.

The Synthetic Turf Council, the industry’s chief lobbyist, assures parents and their children that crumb rubber is safe.

“Science has proven it to be safe for children and people of all ages,” the group’s website states.

The fields were particularly appealing in the Pacific Northwest, where heavy rain turned grass fields into mud pits that were difficult to maintain, especially in winter.

Bryant remembers when Jack was young, loving the turf fields.

“There are no big potholes and puddles,” she said. “The kids aren’t coming home all muddy.”

A growing market

Artificial turf has taken off in the U.S. and around the world. The global market was valued at more than $77 billion in 2022 and is expected to nearly double in the next 10 years. In the U.S., roughly 1,500 new fields are installed every year.

In Massachusetts, Tracy Stewart has battled turf companies and worked to prevent the installation of artificial fields for almost as long as Griffin and Bryant have tracked cancer in soccer players.

Four years ago, Stewart learned about a huge pile of rolled up turf in the nearby town of Franklin. Stewart raised $1,000 “in a hot minute” to pay for someone to test the soil around the discarded turf, which was degrading next to wetlands that are part of Franklin’s drinking water supply.

The tests found that the discarded grass blades and their plastic backing contained PFAS, known as “forever chemicals” for their inability to degrade over time. Exposure to PFAS has been connected to liver and kidney disease, altered immune and thyroid function, lipid and insulin dysregulation, reproductive and developmental outcomes, and cancer.

In 2022, Boston Mayor Michele Wu blocked the installation of new artificial turf in city parks, although a proposed state-level ban in Massachusetts failed to pass. In California, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a law in October 2023 that allows California cities to ban synthetic turf, but he stopped short of backing a bill that would have banned PFAS in fake lawns.

No laws regulate artificial turf in Washington state. A bill in 2016 would have required installers to test for dangerous chemicals, but that measure did not make it out of committee.

In civil court, however, Electron Hydro was fined more than $1 million in 2023 for putting thousands of yards of artificial turf in the Puyallup River. The EPA reported that crumb rubber from the turf was found at least 19 miles downstream.

RELATED: Dam owner pleads guilty after spilling turf, tire bits in Puyallup River

After that discovery, three tribes, including the Puyallup Tribe of Indians, filed a petition asking the EPA to ban the manufacture, use, and distribution of a chemical known as 6PPD, a tire-rubber stabilizer that degrades into 6PPD-Quinone, which kills coho salmon.

The state’s defense

Cathy Wasserman, the state epidemiologist for policy and practice at the Washington Department of Health, defended the findings and methodology of the state’s 2017 crumb rubber study. She said state researchers followed the Department of Health Guidelines for Investigating Clusters of Chronic Disease and Adverse Birth Outcomes, which is standard for investigating potential cancer clusters.

Although Griffin’s list has increased six-fold since the state study was conducted, Wasserman said in an email response, “We do not have plans to revisit the issue at this time.”

Griffin and Bryant learned about the findings at a community center in Kent along with many of the young people who had cancer, parents of kids who had passed away, and adults who had cancer after playing for years on artificial turf fields. It was the first time Griffin had met many of the people on her list and their parents face to face.

“They didn’t even try,” Griffin said. “They literally took my list — that started on a yellow legal pad — of people who I'd randomly bumped into, apparently, [and assumed those] are all the people in the state of Washington who play soccer and have cancer.

“It left me more aware of how politics work.”

Precaution v. Profit

David Kriebel, director of the Lowell Center of Sustainable Production and an award-winning professor of epidemiology, said the use of crumb rubber as infill points to a fundamental problem in the U.S. — the lack of the precautionary principle when it comes to chemical regulation.

Kriebel said efforts to prove cancer clusters “after the horse is out of the barn” are a losing cause.

“You're just gonna make everybody angry, and you're not going to conclude anything. And we'll go on making this mistake, waiting for clear evidence. We don't need it. We have clear evidence of hazard,” he said. “That's enough.”

Griffin has grown frustrated with scientists and state officials who don’t understand soccer, in particular the exposure soccer goalies have to crumb rubber.

RELATED: EPA sides with tribes on petition to regulate toxic tire chemical that kills salmon

For decades, she has interacted with the same demographic, recruited kids from the same player pool, and worked with young girls in goal from the time they were in grade school through college. For 15 years, she heard of no cases of young people, especially children, who played in goal being diagnosed with cancer. All that changed in the years after crumb rubber fields were installed across the Northwest.

Griffin started noticing this shift at Seattle Children’s Hospital, where she would take players to spend time with children diagnosed with cancer and receiving treatment.

The kids talked about their hobbies and loves. Around 2010 or 2011, young cancer patients started telling Griffin they were goalies.

“It went from zero people and then all of a sudden, all these people started popping up at Children’s Hospital,” she said. “Oh, I’m a goalkeeper. I’m a goalkeeper, too.”

Griffin lives in the same north Seattle community where she works. She visits all the soccer fields in the area to recruit players, watch games, and lead soccer camps.

“The one thing that’s changed in our community is the soccer fields,” she said. “There's hardly any grass anymore. They've all been removed.”

People often suggest that Griffin study crumb rubber herself. They have offered her lab space and suggested that she do her own study with rats, one group living on a base of artificial turf and another on natural grass. But Griffin is not a scientist.

“We're the rats right now,” Griffin said. “These kids are the rats.”

Follow-up

Scientists Rachel Massey and Richard Clapp believe the only way to counteract what they see as a misleading cancer cluster investigation is to conduct a well-designed case control study.

In their letter to the Department of Health, Clapp and Brown recommend a study focusing on leukemia and lymphoma in young people between the ages of 15 and 29 that takes into account their playing level and amount of exposure and provides for the lag time associated with the development of cancer. In her dissertation, Massey suggests limiting the study to King County as opposed to Washington state, because the majority of people on Griffin’s list live in the Seattle area.

But Clapp said that case control studies can cost millions, if not tens of millions of dollars. They require what he calls “shoe leather epidemiology,” meaning that researchers have to go out and interview soccer players to gauge their level of exposure, their years of play and how much of that was on artificial turf.

He has seen such studies receive funding, but they require grassroot efforts, community action, and activism.

“That’s citizen pressure on politicians leading to the appropriation of enough funds to do these studies,” he said.

Until that happens, Clapp advises parents and their kids to avoid artificial turf and limit their exposure as much as possible.

“I think we have too much cancer in this country, and the reason that we have it is because we’re exposed to too many carcinogens,” he said. “If we can reduce that, good.”