Freeze! Police! What happens when people get caught doing drugs in Seattle?

While opioid deaths continue to skyrocket, politicians and advocacy groups in Seattle have engaged in a months long battle over drug policy, trying to figure out how to manage the open use of narcotics in city buses, trains, parks, and practically every other public space.

Now that the dust has settled, what does the city's new drug ordinance mean for people who use drugs in public and others who witness or are otherwise impacted by that use?

Two things happened in the past month to help clarify and implement Seattle's new approach to public drug use and possession:

- On Tuesday, Sept. 19, the Seattle City Council voted 6-3 to make drug use and possession a gross misdemeanor. The move aligned city code with state law and ended a period of uncertainty about who is responsible for enforcing drug crimes in Seattle, or even what constitutes criminal activity.

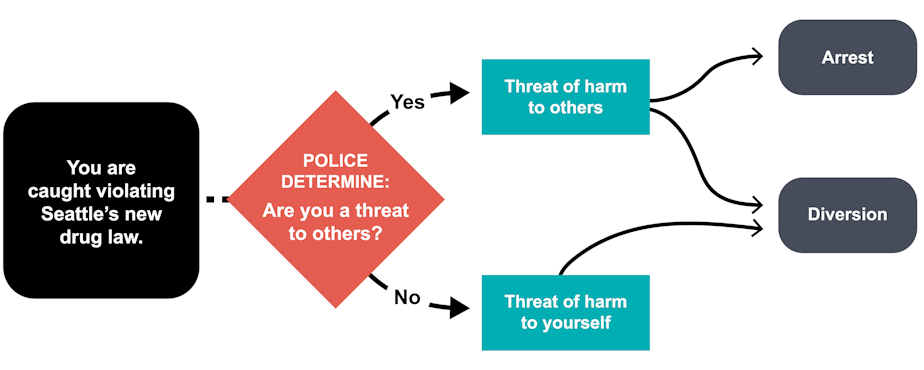

- On Thursday, Sept. 28, Mayor Bruce Harrell issued an executive order that explains how police should enforce Seattle's new drug ordinance. Harrell's order attempts to balance public health and public safety by offering police guidance on how to enforce the new law. The order says police should only arrest people if they determine that someone poses a danger to others.

How does it work?

Sponsored

What counts as drug use and possession?

Drug use and possession is now a gross misdemeanor in Seattle, punishable by up to 180 days in jail or a fine of $1,000. Those penalties increase after two offenses. The ordinance applies to the possession or use of a controlled substance, "unless the substance was obtained directly from, or pursuant to, a valid prescription or order of a practitioner while acting in the course of his or her professional practice."

While "controlled substances" are defined by state law to include a variety of drugs, including cannabis, the focus of the drug ordinance and Mayor Harrell's executive order is on opioids and meth, according to Jamie Housen, director of communications for the mayor's office.

Possession and use include:

- Selling or purchasing narcotics

- Admitting to narcotics possession

- Open possession of narcotics or paraphernalia with narcotics residue

- Narcotics in plain view

- Open use of narcotics

Sponsored

How is someone deemed a threat to others or themselves?

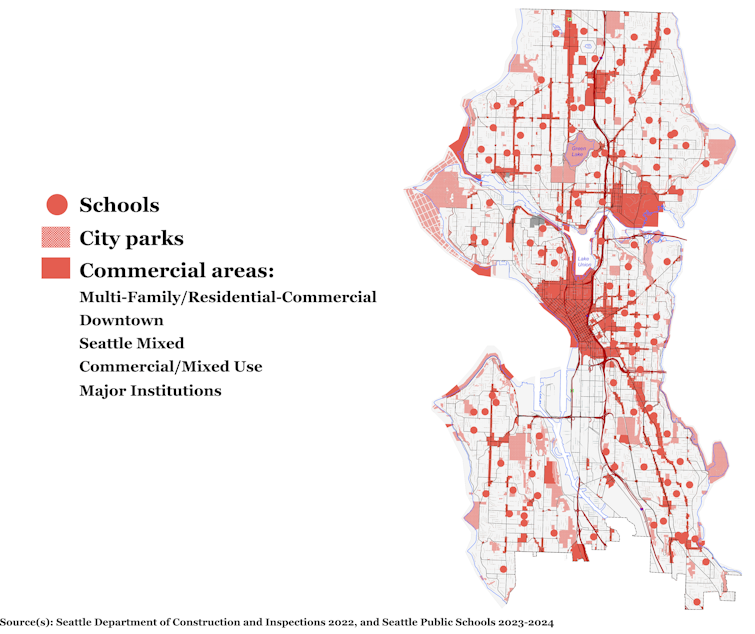

According to Mayor Harrell's executive order, a threat of harm to others includes public use in close proximity to businesses, organized activities, child care facilities, schools, parks, and transit. A 2022 map of Seattle's generalized zoning shows areas that could be most impacted by this ordinance.

Seattle areas where public drug use is more likely to be deemed "a threat to others" based on the combination of high density, mixed-use zoning, parks, and schools.

Police can take into account the type of narcotic used and the physical condition of the person found using or in possession of the drug when making a determination about how to proceed.

Sponsored

If someone is deemed a threat to themselves, officers should make a reasonable attempt to contact and coordinate diversion or other alternatives to arrest, according to the executive order. A lack of diversion options is not a reason for jail booking and referral to prosecution.

Housen explained that the order prioritizes diversion programs over arrest, regardless of the threat determination made by officers.

"Diversion is the preferred approach even where there is a threat of harm to others," he said, "but officers are expected to use their discretion."

Sponsored

How many people could be arrested or sent to diversion programs?

Arrests

So far in 2023, Seattle Police have made close to 300 narcotics-related arrests, just over 4% of the total number of arrests (6,781) citywide, according to the Seattle Police Department's Arrest Dashboard.

In terms of Washington state, law enforcement reported almost 7,000 incidents categorized as "Drug/Narcotic Violations" in 2022. Amphetamines, meth, and narcotics accounted for 1 in 3 of those offenses. Only 20% of the drug violations resulted in arrests.

While it is impossible to predict how the new drug ordinance will impact King County diversion programs or test the capacity of city jails, it is clear that Seattle is in the midst of an escalating drug crisis. In 2022, the city recorded 589 overdose deaths, the majority attributed to fentanyl and meth, a 72% increase from 2021.

Sponsored

Those numbers are only getting worse in 2023. Seattle Fire Department paramedics and EMTS have responded to more than 4,000 overdose calls so far this year, already surpassing the total number of calls in 2022.

What's more, there is growing evidence that people injecting and smoking opioids are doing so regularly and openly in public spaces. A study by University of Washington researchers found meth and fentanyl on bus and train surfaces, as well as drug fumes lingering in the air on public transit vehicles throughout Seattle.

Arrests and prosecutions are also dependent on the King County Jail accepting bookings under this ordinance and the city attorney filing charges. After the city passed the drug ordinance, City Attorney Ann Davison said she was "relieved."

“We really do need to be intervening with people in a meaningful way and making our public spaces safer, so I’m glad we can proceed on that,” Davison said while touring a drug treatment facility with Mayor Harrell Sept. 20 in Seattle's SoDo neighborhood.

The executive order also requires arrest reports to document facts used by police to establish probable cause and assess the level of threat presented. The reports must also note whether diversion was considered or attempted in drug-related arrests.

Sponsored

RELATED: Seattle program addresses key gap in the opioid crisis: post-overdose support

RELATED: There's meth on that: Study finds drug traces on Seattle transit rides

Mayor Harrell's executive order also includes measures that allow the city to collect data and gauge the effectiveness of the new law. For example, the new data would allow city officials to compare the number of people referred to diversion programs with the number of people arrested for drug use and possession.

The executive order also advocates for the legalization of fentanyl testing strips to help people addicted to drugs check the quality and purity of drugs before they take them. The city also plans to "explore funding for" additional locations to distribute naloxone, a medication that can save someone's life if they have overdosed on fentanyl.

Referrals to diversion programs

King County has a variety of diversion programs that "seek to divert individuals from incarceration and hospitalization and into community treatment settings." County programs are divided between pre-booking diversions and crisis diversion facilities.

Crisis diversion includes:

- Residential treatment facilities that provide services for people experiencing a behavioral health crisis. The maximum length of stay is usually 72 hours.

- Interim services that help people find housing or connect them with other support options once they are stabilized.

- Mobile crisis teams that respond with police and first responders to provide immediate services to people who are suffering from substance use disorders or other mental or physical crises.

Capacity of existing diversion programs:

It is unclear what happens if all diversion programs are full. KUOW reached out to the Seattle Police Department and the King County Department of Community and Human Services about where programs stand in terms of capacity.

In terms of treatment beds and facilities where a person could be referred, Katie Rogers, communications director at King County Department of Community and Health Services, said the county has the following options:

- 49 beds for withdrawal management (33 acute, 16 secure).

NOTE: King County contracts with these locations. Rogers said there are a handful of additional locations, but they are cost prohibitive and require people to be in their treatment program already in order to receive care. (As of Oct. 3, the 33 acute beds were full.)

- 128 beds for substance use disorder in-patient treatment (16 youth, 112 adult)

- 66 facilities for substance use disorder outpatient treatment (not including services provided by Sovereign Tribal Nations and Indian Health Programs)

- 12 walk-in clinics that provide same-day, on-site Buprenorphine inductions, which provide relief from opioid withdrawal.

- 160 programs that provide access to medications for opioid use disorder

- 9 locations for medication-assistant treatment services

While that might sound like a lot of services, Rogers said it remains a challenge for the county to meet the growing demand for drug treatment, especially when it comes to serving people suffering from withdrawal.

"In terms of need, for a county of 2.3 million people there are limited facilities in the county with withdrawal management beds," she said in an email.

Seattle Police referred reporter questions to the LEAD/REACH program. A voicemail message at the REACH program suggested that all referrals to the program have to come from official sources, such as first responders or hospitals.

"Unfortunately, due to capacity we are not accepting any new clients via self-referral or outside referrals at this time," the message said.

The new drug ordinance goes into effect Oct. 20.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This article was amended on Oct. 5 to more accurately explain the relationship between King County and facilities that provide beds for withdrawal management, which is defined by county officials as a safe, medically monitored environment for people experiencing withdrawal symptoms.