'Good but glitchy.' A kids’ view of remote school, from a Central District youth center

Glitchy computers. Distracted students. Overbooked parents.

Seattle families are still troubleshooting daily routines and challenges, nearly a month into remote school. Some have turned to childcare or youth centers that have rejiggered programs to give kids a place to spend their remote school day and get some extra, hands-on help.

A girl in a pink sweatshirt and three pink hair clips lays her head on the table at the Central Area Youth Association (CAYA). She's quick to point out that she’s the first student here, every morning.

“I got here at 7. It takes so long and I have to wake up really early to start,” she explained.

Kids trickle in and most start off with a bowl of cereal. Parents head off for work; one mom is wearing scrubs, fresh off the night shift.

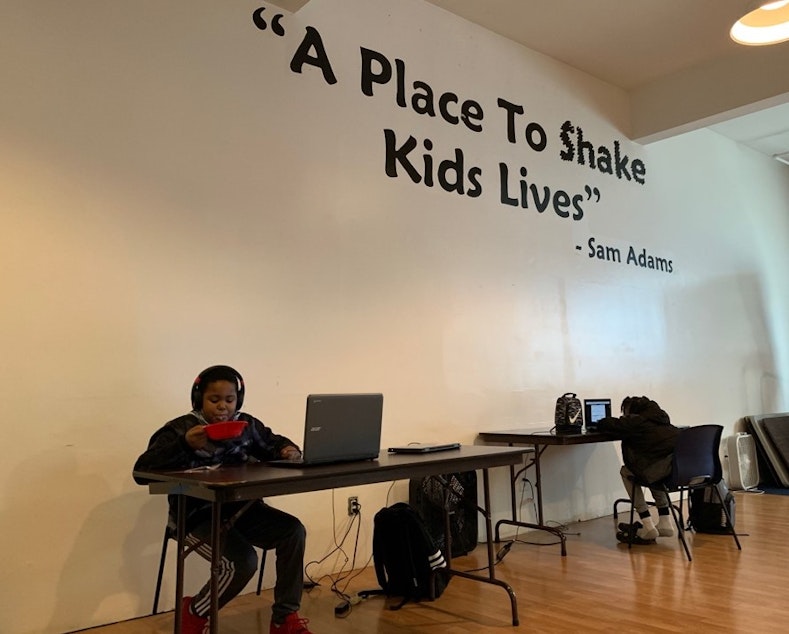

CAYA has made space for 15 students, most who have been coming here for years for after school clubs or summer break camps. But this pivot to all day school is new for everyone.

Sponsored

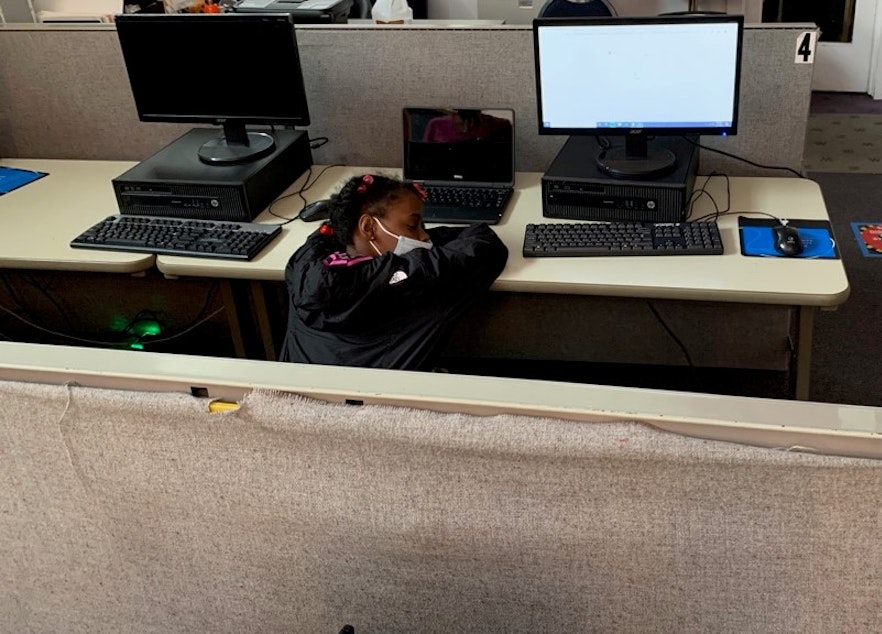

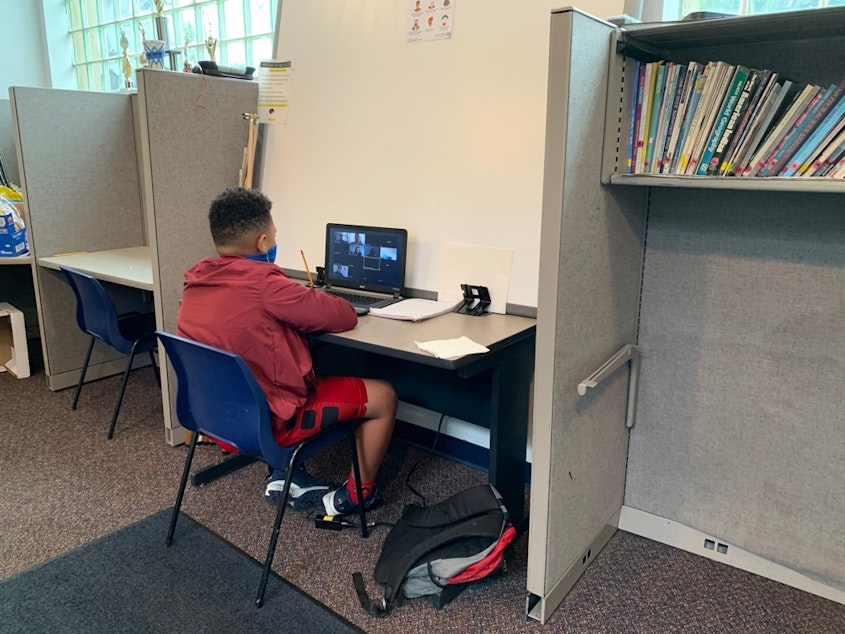

Remote classes start at 8:30 and the seven kids here so far spread out to separate work stations, with their school-issued laptops or iPads.

Soon, the tech glitches begin — still, in this third week of school.

“I can’t get to the big screen,” one girl complained as she tried to connect to her Zoom classroom. “Arrgh! Stupid thing!" she cried.

Another student can’t get her microphone to work, and the lone kindergartener here — her iPad is dead. (It’s Monday.) Program director Aleja Amesquita pops from station to station, helping where needed and also giving kids room to problem-solve on their own.

Sponsored

“They know how to fix a lot of this,” she said. “They can be pretty self-sufficient.”

Eventually, everyone is Zoomed into their separate remote classrooms — each with separate teachers and separate lesson plans, from kindergarten through fifth grade. During the morning break, a few students shared their thoughts about how things are going so far.

“It’s going good, good,” said Elijah Baker, 9. “But my computer was glitching...for like an hour. Restart, wait...blah blah blah.”

“You have to just sit around all day, and you can’t really be running that much,” said Miles Jenkins-Beaumonte. “Then your legs get tired and fall asleep.”

Sponsored

Asked about wearing a mask all day, Queen-Alini Ropati-Vao, 9, proclaimed “it's great.”

“But you can struggle a lot, it could hurt your ears,” she said. “But we have to; we have no choice. A lot of people died because people are not wearing these masks.”

The kids in this CAYA program are all students at nearby Leschi Elementary, where nearly half the school families identify as low-income. This remote learning program is free to families who need it, in situations when parents are working, or there’s no internet at home, or students need extra support.

Sponsored

The Seattle School district provides a list of about 50 fee-based childcare partners, some that charge up to $1,400 per month. A spokesperson said families can apply for free or reduced tuition, and scholarships are often available.

For these Leschi students, the feeling seems unanimous: They miss their regular school.

“I loved going to Leschi,” Elijah said wistfully. “I love the lunch and I can teach and talk to my students. But now we can’t. We can’t play, hug, high five, have sleepovers.”

“I just miss, like, having fun and doing fun activities,” Queen said. “I just want to go back but we don't know if we’ll go back.”

Queen also noted that she’d like to be learning more in remote school and that what she’s most looking forward to when school restarts in-person is “listening and following directions.”

Sponsored

Around noon, a Leschi staffer brings school lunches for the kids; a choice of turkey or tuna sandwiches. Most kids eat the cinnamon bun first.

Then during the break, the kids work off some extra energy playing basketball in the gym, dancing to TikTok videos, or tapping out notes on the organ. Queen, however, is back at her computer, watching worldwide wrestling videos. She’s a big fan.

When school lessons start up again for the afternoon, Amesquita gets a quick breather from running around to help each student stay on task and tuned in.

“They need structure, discipline, supervision and just guidance — someone to be available to answer any questions that they might have,” she said. “Like without that, I don't believe that they would be doing this in their online classrooms — doing their homework. But there’s only so much we can do.”

It’s a community effort, she said, with teachers, schools and parents.

And they could use more tech support, please! A common plea from parents across the district. (A week after KUOW’s visit, in week four of school, Amesquita said the tech issues have somewhat improved.)

Still, the kids seem to mostly take it all in stride and soldier on.

“I feel like I got this,” said nine-year-old Queen. “Like I could go to school on my own, like how my brother does.”

But the idea of regular school starting up again, that puts a spark in her eye.

“Oh, I'd be so excited,” she said. “I just want everything to go back to normal. I just — I just miss it.”

Her schoolmate Elijah wishes he could make that happen.

“I want superpowers and corona to be gone,” he said, waving his hands like a magician. “Just be gone. Just be gone.”

“Be gone,” he whispers.

Editor’s Note: The author’s son also attends Leschi Elementary.