We spend 12 million hours a week on the phone with health insurance

This past summer, Rupali Limaye says she "sort of became the vaccine lady at the pool."

She's a behavioral and social scientist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, so it made sense that other parents were coming to her for information. Limaye has also spent the past decade studying vaccine hesitancy. In that work, she has come to understand deeply that when someone has doubts, hearing the facts from someone the person knows well can be a powerful force in overcoming those doubts.

She knows, too, that not all families have that kind of relationship with a doctor. "We've had such an erosion of trust in the health care system and in public health," she says "that we should really leverage the peer-to-peer approach, right?"

So Limaye and Johns Hopkins have created a free two-hour course on the online platform Coursera that's open to anyone. It's called COVID Vaccine Ambassador Training: How to Talk to Parents.

Their goal is to prepare everyone, from principals to PTA presidents, to counter misinformation with empathy and, ultimately, to move more people to seek out the lifesaving vaccine. As of Jan. 18, just 28% of children ages 5 to 11 had received even one COVID-19 vaccine shot.

Sponsored

Here are Limaye's top evidence-based steps for having a conversation with someone who isn't sure about vaccines:

Presume the desired behavior is the norm. This is called "presumptive communication," and there has been research on how it can positively influence people's choices and beliefs around behaviors like drinking or sexual harassment. Parents can set a positive social norm around vaccines by posting on social media when their own children are vaccinated or by bringing it up at the playground: "Hey, we got Ethan his second shot last week. When is your son getting vaccinated?" or "Wow, did you see there were 150 people at the school's vaccine clinic on Saturday?"

If someone expresses doubts, ask open-ended questions like these: "How do you feel about this?" "What are you worried about?" "How can I help you think through this?" "What would help you make a decision?" You need to understand their specific concerns in order to counter them successfully. This is called "tailoring" the message to the person.

Listen. Listen actively, with your phone turned off. No rolling eyes, crossing arms or looking away, which are signs of disrespect or defensiveness.

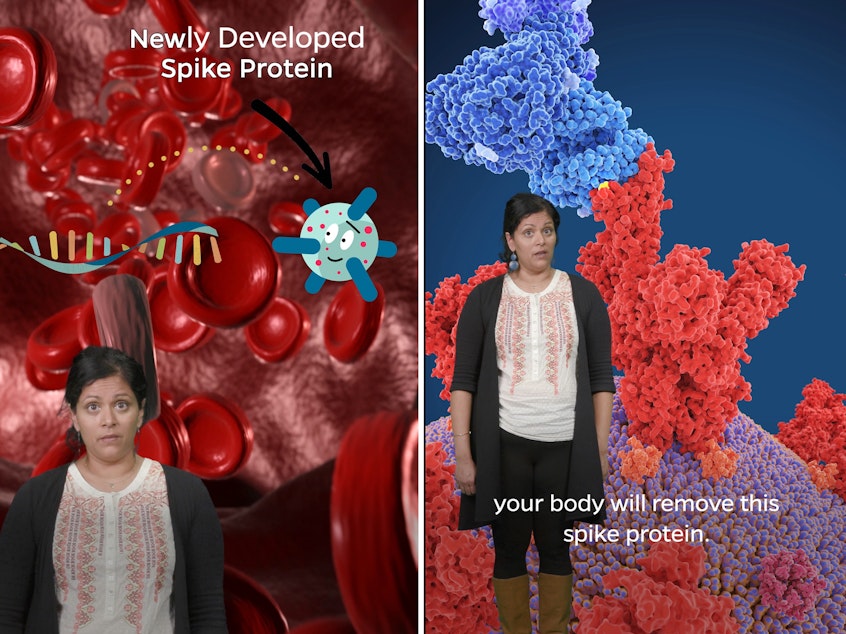

Show empathy to build trust. Affirm their choice to be in the conversation: "I'm glad you're taking the time to learn about this." And validate their emotions, without validating the misinformation that may drive them. For example, if someone tells you that the vaccine changes your DNA, you can respond: "That would be really scary! Of course you want to make sure that vaccines are safe. The good news is that no vaccine can change your DNA, and I can share information with you that could help you understand the science behind it."

Sponsored

Debunk misinformation and myths. Limaye says many people skip straight to this step, thinking the best antidote to bad information is good information. Not so.

"While I can explain how there is no microchip in the vaccine," Limaye says, "it's really important for me to be able to listen and be empathetic instead of being dismissive."

If someone states a false belief, you can, again, validate them by acknowledging that it's hard to make our way through the disinformation landscape. Then pivot to the truth, says Limaye: " 'I understand that there's a lot of information out there, and it's really hard to discern what is true and what is not true. Let me tell you what I know.' "

What's happening there, Limaye says, is that "I'm pivoting the conversation slightly to sort of be like, 'OK, here's how the vaccine was made, which means there actually is no microchip in the vaccine.' "

When it comes to the facts, be clear and simple. Repetition is your friend. Try telling a personal story that underlines the real risks of the coronavirus and how those risks outweigh the risks of the vaccine. And ask permission before directing people to trusted resources where they can learn more.

Sponsored

Limaye knows these conversations won't be quick or simple. But at a time of extreme polarization, she hopes people are empowered to try becoming an "ambassador" for empathy. [Copyright 2022 NPR]