It's an annual tradition in Seattle: Promise more money for housing than ever before

On Monday, Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan announced an unprecedented $110 million in spending on affordable housing.

Spending on housing has gone way up. And there's a reason for that.

In December of 2015, long before scandal would force him from office, then-Mayor Ed Murray stood before a podium and announced the city would invest $45 million in affordable housing. It was double what the city has spent the previous year and demonstrated that this mayor, who had just published one of the most rigorous analyses of the housing shortage ever, was serious about fighting homelessness.

He had to do it, in a way. Ten years earlier, the city had pledged to end homelessness in ten years. The spectacular failure of that pledge seemed to require an equally spectacular response.

And while the bulk of money pledged in late 2015 came from the housing levy passed by voters, some experiments in alternative sources of funding had begun to generate income.

Developers were paying for the right to build larger buildings in a pilot program you might call the "ancestor" of today's Mandatory Housing Affordability program (MHA).

Sponsored

Today, that pilot program has been replaced with a much larger one that covers much of the city. Other strategies, such as getting Olympia to give up some of its taxes, were also called for in Murray's housing affordability and livability (HALA) roadmap and have begun to pay dividends as well.

Others strategies, such as convincing the federal government to increase its investment in housing, have faltered.

Since Murray stood at that podium in December 2015, the city's approach has been rejiggered and rebranded.

But the work begun back then has helped the city's annual spending announcement reach its current spending peak under Durkan.

And yet, as funding for housing continues to grow dramatically, homelessness has not seen an equally dramatic decline. Part of the reason, experts say, is the dramatic economic inequality felt so distinctly in tech hub cities like Seattle.

Sponsored

"Unfortunately the need outstripped our capabilities," Durkan said Monday. "But today we take another very important step forward."

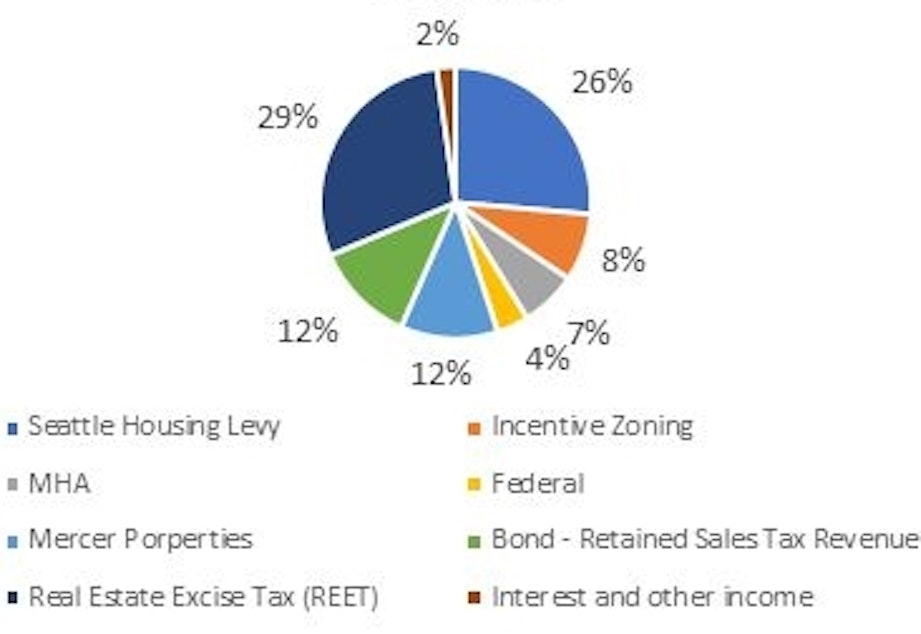

Much credit for the latest rise in spending goes to developers, who paid 7% of this year's funds through the MHA program, and to the state legislature in Olympia, which allowed Seattle to capture some sales taxes that would otherwise have gone to the state, and to the City Council, which led the charge to take advantage of that right.

A big chunk of money also comes from the sale of the "Mercer megablock" property, a sale sought by the mayor.

Inflation has played a role, as has the frenetic pace of construction and rising property taxes.

The result is that when the mayor stands at the podium, she gets to promise more money for housing projects like the Africatown project in the Central District, The Lam Bow project in Delridge, or the Nesbit Family Housing planned north of Green Lake.

Sponsored

"We as a culture... we live together, and we love that," said Ethiopia Alemneh, a board member for the Ethiopia Village project, which received funding this year. "And our seniors are in a lot of mental crises right now because they live scattered areas."

After the press conference, she showed me the parking lot next to the Ethiopian Community Center where seniors drive in from all over the county to connect with friends and relatives and to receive services.

"Imagine living here and getting services," she said, gesturing to the parking lot. "It's really amazing."