It's not just you. The pandemic has made us all a bit awkward

When Lisa Curdy ventures out to the grocery store or other basic errands around Seattle, she can't help but feel like something is off.

"Checkout lines are quieter; can't get too close to talk, and sometimes masks make it hard to understand. Human interaction is abbreviated," she said. "And most of all, I feel like there's this weird divide..."

Curdy has maintained a social bubble through months of pandemic lockdowns and restrictions in Washington state. Within that bubble, things are pretty normal. But outside of it — "Nothing but weird. Because after all this time, what do we have in common anymore?

"I feel like finding that space, that comfort, is going to take practice," she said. "The kind of practice that comes with figuring out how to interact with people, all over again."

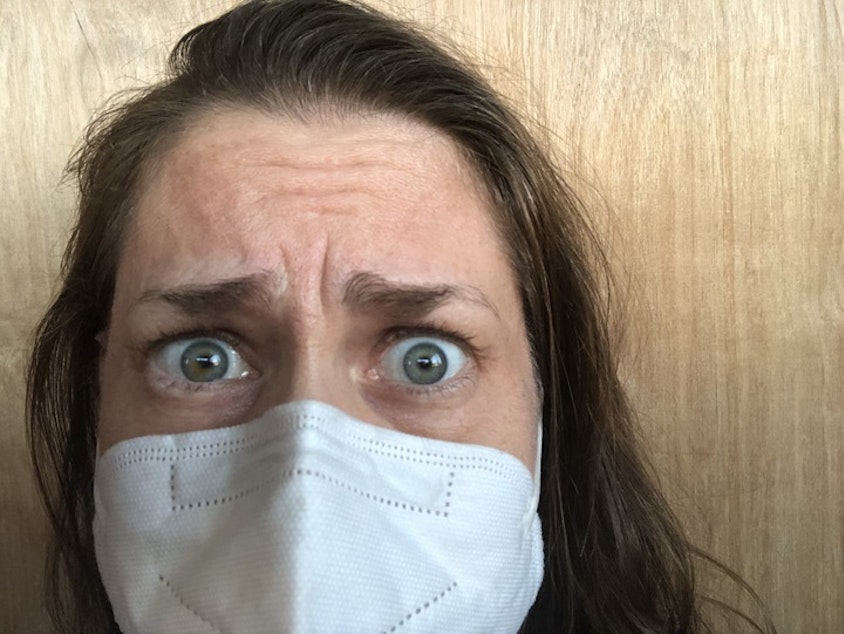

Curdy is not alone. She's among a crowd of people who report, anecdotally, that interacting with others takes more effort than usual these days — like a loss of social equilibrium you didn't know was there in the before Covid times. In short — it's strange. And it's even led to weird expressions of awkwardness, like this guy.

Sponsored

Christy Scheuer, also from Seattle, echoed Curdy's sentiment.

"I do feel like my interactions with people are very tentative and uncertain," Scheuer said. "Since I don't talk to people outside my household very often, every conversation I do have, has this sense of urgency and emotional intensity. But that intensity doesn't match the situation, so I find myself talking too fast or fumbling for something to say."

As Scheuer puts it, it's the kind of interactions that would prompt awkward, moody diary entries while learning the social rules of high school.

The pandemic has upended a range of routines, social habits, and aspects of daily life. From running into friends at the grocery store to chatting with cubicle pals, some are striving to get their sea legs, for socializing.

Social sea legs

Sponsored

If you ask Patrick Raue, clinical psychologist and professor in the Department of Psychiatry at University of Washington, this is all to be expected.

"What was a natural give-and-take now may become a bit more effortful to get into those comfortable patterns," Raue said.

"We all may be going through somewhat awkward interactions, as we're kind of renegotiating new norms," he said. "Most of us are not shaking hands with colleagues or friends or strangers, or we're not hugging friends, we're not getting too close. But also, not everybody has the same mindset...some people are following the recommended [pandemic] guidelines, and some people are kind of doing their own thing."

Raue believes people are likely juggling being hypervigilant while also negotiating every interaction. That amounts to a lot of uncertainty.

During the pandemic, Raue has been working on improving the mental health of older adults, especially amid various physical distancing requirements. Through a program called "Stay Connected," he has helped develop methods for long term care facilities to decrease loneliness and anxiety for older adults, and generally help them feel more connected to others. While his focus has been on older adults, the lessons are good for everybody.

Sponsored

He notes that these factors can be exacerbated for people who managed social anxiety before the pandemic. For everyone, he likes the analogy of "sea legs." The solution, as queasy as it sounds, is to just set sail.

"The very analogy of sea legs is that you develop them with repeated practice and opportunities, and you're not going to master it in your first couple of encounters," Raue said. "So it takes time. And to not disengage and avoid, but to kind of welcome those opportunities to develop your sea legs. Even if they're a bit awkward or uncomfortable at first, that's part of the process."

Curdy said she's still adjusting to the uncertainty and navigating how to connect; she's finding her sea legs. And for now, Scheuer said she's relearning how to chit-chat, but still finds herself longing for better times.

"In June, I had a minor surgery, and there were a lot of doctor appointments leading up to it," Scheuer said. "I find myself feeling oddly nostalgic for that time — I was talking to so many people! My dad dropped me off for surgery, so we were able to ride in the same car. And when my husband picked me up, he had to leave our children with our neighbor, and they were ecstatic. I just remember it as this really lovely day. At least, until the anesthesia drugs wore off."

Tips from Dr. Raue

Sponsored

One factor that can hinder any progress is negative thoughts. We all have them. Be aware of them and develop a tactic to counter them.

"These automatic negative thoughts that might come up to you," Raue said. "'I'm awkward, I'm making a mess of this, I'm gonna say something foolish, or they're gonna think that I'm awkward' ... it's important to be aware of those and slow that thinking process down and challenge those thoughts. Be as realistic as possible.

"What's the evidence that this is truly, horribly awkward and aversive? Have a conversation from the other person's perspective. How can you come up with some coping statements or some challenges statements to kind of be as realistic as possible about your 'performance?'"

Also important: don't hide away.

"Avoidance and cutting yourself off, whether you're feeling depressed or anxious...is a common reaction. Because it means that we're avoiding the exertion, we're avoiding the discomfort. But unfortunately, that works against us. Because that can create this vicious cycle. You've trained your brain that the only way that 'I'm safe' or comfortable is by withdrawing.

Sponsored

"And so it takes effort and it takes discomfort to start, but that is the way to unwind that vicious cycle and to feel calmer and less awkward and more engaged with other people. Even if it feels awkward at first, that's OK. It's part of the process."