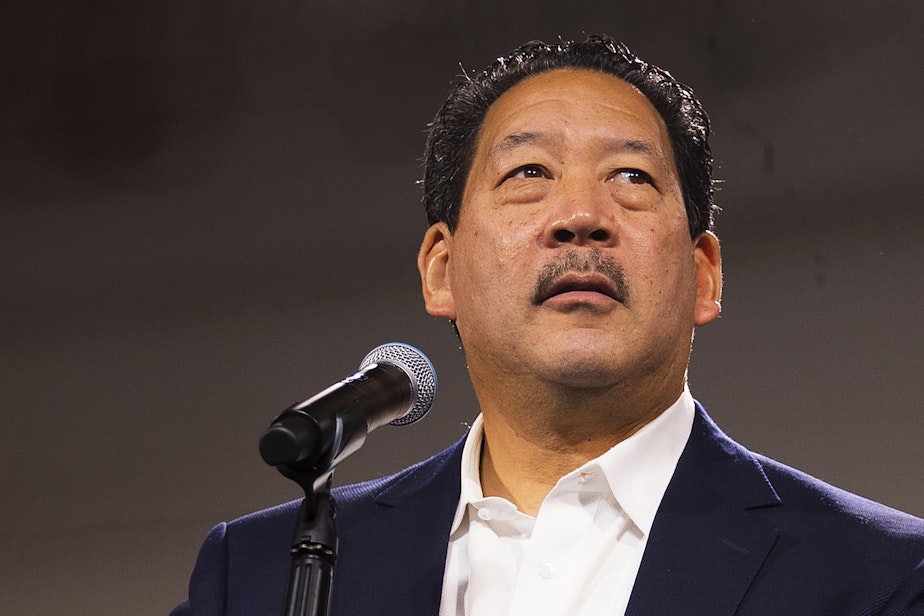

Monisha Harrell breaks silence on her uncle – and former boss – Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell

Monisha Harrell was walking behind her uncle, Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell, in late 2022, when she overheard him say something to a colleague that stopped her in her tracks.

“SDM Nazi.”

SDM – she knew that was her. It stood for senior deputy mayor. Monisha Harrell later learned that SDM had become an inside joke to her uncle and the men on his executive team – to them, it stood for So Damn Mad or So Damn Mean.

Monisha Harrell was stunned by the casual cruelty. She asked herself, “How well can I actually serve the city when I'm being disrespected, and it's coming from the top?”

Monisha Harrell learned the nickname had gotten around the office. A former high-level city staffer confirmed the nickname to KUOW; spokesperson Jamie Housen acknowledged the SDM nickname may have arisen “during the course of friendly banter” but said he could not remember what the acronym stood for.

Sponsored

“Our office is a place where we share nicknames and jokes with one another,” Housen said.

Monisha Harrell is breaking her silence for the first time since she left her uncle’s administration in 2023. She describes the mayor’s office as being a dog-eat-dog environment where white male advisors vied for power and influence. She said her experience, as a high-level woman ignored by the mayor and his lieutenants, is not unique at City Hall.

Monisha Harrell initially shared her story with KUOW soon after she left the job, but she did not want to go on record. She said she’s coming forward now to give voice to other women who left the mayor’s office and the City Council because of what they called a toxic work environment.

“I didn't do it for me,” Monisha Harrell said about coming forward. “There were a lot of talented women (at the city) undermined and pushed out of positions they worked very hard for.”

Bruce Harrell appointed Monisha, his niece and campaign manager, to be his second-in-command after he was elected in 2021. Bruce was a beloved uncle who helped raise her, with whom she had celebrated holidays, and whose children she adored.

But Monisha quietly left the job after a year and a half; a press release from the mayor’s office characterized her departure as amicable. Housen later told KUOW that “Mayor Harrell is proud to have appointed the first Black lesbian senior deputy mayor in the City of Seattle’s history and is grateful for her contributions to our administration. He is also proud to be her uncle and continues to love her and remain proud of her many accomplishments.”

Monisha now works as the director of King County’s Office of Equity, Racial and Social Justice.

Monisha said that as senior deputy mayor for Seattle – the number two spot – her male colleagues went around her to the mayor, in attempts to convince him to see things their way. She said the mayor, who appeared more interested in being a figurehead than engaging in nitty-gritty policy issues, often overturned her decisions.

Bruce Harrell, Monisha said, diminished the opinions of female staffers, including her own.

Sponsored

“I wasn't being trusted to do my job, and that is a really difficult thing to do,” she said. “You can't be successful in your role without having the support of those around you to do it.”

Mayor Harrell dismissed these claims from his niece through a spokesperson.

“The mayor is particularly sensitive to bullying and stereotypes given his own personal experiences as a biracial man,” Jamie Housen, spokesperson, said by email.

Bruce Harrell declined KUOW’s request for an interview. Housen said Harrell had to focus on running the city, “versus a story about a former employee.”

KUOW spoke with six other women with ties to the mayor’s office who supported Monisha Harrell’s account of a boys’ club environment where women were condescended to and shut out of important meetings, even though their roles would suggest they be included.

Although the mayor has hired several women and people of color to key positions in his administration, including three current deputy mayors, Monisha Harrell said that he seemed to value only his white male advisors.

One former female employee described what happened when she raised concerns with the mayor. She said that the mayor summoned her to his office, where he pounded his chest and said, “Are you trying to buck up on me?”

The former employee, intimidated, ultimately resigned. At the time, she shared details of the incident with a family member. KUOW confirmed this conversation with her family member.

Monisha Harrell said that after telling her uncle she was leaving, he replied that he had “only needed her for a year” for optics.

Monisha Harell also learned that her uncle told her intern after she left that Monisha didn’t get along with men in the office and wouldn’t collaborate with them.

The former intern confirmed this conversation with Bruce Harrell. She said that based on what she observed, “I think it was the male employees who wouldn't collaborate with her.”

Monisha said she confronted her colleagues in the mayor’s office about the problematic nickname – SDM Nazi – during a senior staff meeting – telling them it played into the racist trope of the “angry Black woman.”

She said she believed her uncle used the moniker because he was annoyed with her for advocating for fiscal restraint; Monisha oversaw the city’s budget department.

Bruce Harrell had inherited a budget deficit of $141 million in 2022, which ballooned to $250 million by the end of fiscal year 2024, in part because of inflation and interest rates. Monisha said she was trying to close the deficit to avoid layoffs.

“I was holding the purse strings pretty tight,” she said.

Sponsored

Bruce Harrell would travel to domestic and international destinations, Monisha said, while she advocated making cuts to the mayor’s office budget. And while the mayor’s travel costs were sometimes covered by outside groups, expenses racked up for the colleagues and executive protection that escorted him. In some cases, the mayor’s protection detail would take advance trips.

Spokesperson Housen said in November 2023, “travel is often an essential part of the job for any major city executive.”

Despite Monisha's push for fiscal responsibility, she said the mayor did not change course. Making things more difficult, Monisha said she rarely heard directly from her uncle, who would instead confer with the cadre of men in his office and effectively shut her out.

“When those conversations are happening around you or behind your back, and you don't find out things have been changed until after they've been changed, it doesn't allow you to do your job,” Monisha said.

While the ultimate decision-making authority falls to the mayor, Housen said that Bruce Harrell used a model that ensured “more people are in the room informing decisions and overseeing department portfolios.”

The current executive team includes four women out of 10 people total. Four on the executive team are people of color.

Harrell, outwardly, has condemned sexism and racism during his time as mayor. When former Police Chief Adrian Diaz was involved in officer lawsuits claiming sexism and discrimination, Harrell hired a law firm to examine the harassment complaint process.

After Harrell’s director of external affairs was accused of sexual assault last summer, Harrell said he was committed to rooting out sexual violence. The director resigned.

During the reporting of this story, five current and former staffers from the mayor’s office contacted KUOW unprompted. All requested anonymity and proceeded to disparage Monisha Harrell.

As this story approached publication, the mayor’s office sent glowing statements about the mayor from three women in his office – Deputy Mayor Tiffany Washington, Chief People Officer Aisha Foster, and SDOT Director Adiam Emery.

“The mayor has empowered me and so many other women in our office with the responsibility and authority to make progress for the people of Seattle,” Tiffany Washington said.

“I’m grateful to be part of a team that elevates women, particularly women of color, to influential positions where we can support our communities,” Aisha Foster said.

Six other women, however, also with close connections to the mayor’s office, echoed Monisha’s description of the workplace. Many asked not to be identified, fearing retaliation.

Esther Handy, former director of central staff, worked alongside leadership in the mayor’s office, including with Monisha.

“Monisha brought so much progressive credibility and leadership to the mayor’s office,” Handy said. “But at the end of the day, that meant she had some power, which was unacceptable to the mayor, his agenda, and the men vying for power around him, who began going around Monisha to undermine her credibility.”

Monisha Harrell said that a recent exodus from City Hall, including the publicized departure of progressive Councilmember Tammy Morales, prompted her to speak up.

In December, Morales announced she would quit the Council come January, because she said her mental health had been impacted by colleagues who bullied her and prevented her from doing her job. Fellow council members painted Morales’ departure as an overreaction.

Morales said the toxicity she experienced on Council extended to the mayor’s office.

“We call it the Hunger Games,” Morales said in December. “It doesn't feel like this mayor has a particularly clear vision for what he wants the city to be, and so each of these deputy mayors kind of has their own area, their own little fiefdom of things that is in their portfolio. And it feels like they all sort of vie for who gets their work prioritized.”

Monisha Harrell experienced this, too. The mayor would call votes on issues that fell squarely under her authority. That’s when she found herself surrounded by white male coworkers and subordinates -- some of whom held lower seniority -- casting votes of equal measure to Harrell’s on important issues even though they lacked her knowledge and expertise.

“It’s one thing if you get a seat at the table and lose a vote, but when your seat is not authentic, and not authentically part of the discussion, that’s when it’s a problem,” Monisha said.

Monisha recounted a time when she was called to meet with the mayor and found herself at a conference table with seven white male staffers. Aside from the mayor, she said she was the only person of color in the room. She was the only woman in the room.

The meeting pertained to post-pandemic, return-to-work public safety concerns, which was part of her portfolio at the time. Monisha Harrell was the police chief’s supervisor, had served as a deputy monitor of the Seattle Police Department’s consent decree and was a driving force behind voter-approved Initiative 940, which required deescalation training for all law enforcement officers in Washington state.

She presented her perspective; The mayor called on someone to give a counter perspective.

“Okay, well, why don’t we just take a vote?” the mayor said, according to Monisha Harrell.

The vote was 5-3, against Monisha Harrell’s recommendation. The mayor accepted the vote without weighing in.

That’s when she realized, although she was seated at the table, she wasn’t a player.

“It is a hard thing to serve when you are surrounded by people who are more attracted to the power than they are the work,” Monisha said.