Part 2: The Swindle

Cowboy Cody Easterday lies big by creating a “ghost herd” of 265,000 cattle that only exist on paper and bringing in hundreds of millions of investment dollars from companies, including a meat-packing giant. It’s fraud on a massive scale. We examine how he carried it out.

It started as an American success story. The Easterday family took a couple hundred acres of farmland in southeast Washington and grew it into a farming and ranching empire worth millions. Then, it all came crashing down.

"Ghost Herd" tells the story of Cody Easterday, the man at the center of one of the largest cattle swindles in U.S. history. Easterday invented a so-called “ghost herd” of 265,000 cattle that only existed on paper … and swindled companies including an agriculture giant to the tune of $244 million dollars. Correspondent Anna King has spent two years following the fallout of the crime and its impact on a tight-knit rural community.

"Ghost Herd" is a story of family and fraud, but also a story about the value of dirt and the shifting powers in the American West.

Search for Ghost Herd in your podcast app.

Ghost Herd is a joint production of KUOW Puget Sound Public Radio and Northwest Public Broadcasting, both members of the NPR Network.

Sponsored

Episode 2: The Swindle

Transcript:

Anna King narration: When I first started reporting here in the Columbia Basin, I was in my 20s. My mom gave me kisses, dad threw a last-minute Costco pack of toilet paper into the back of my rig, slammed the trunk, gave me a huge hug, and I drove east over White Pass.

Sponsored

I was reporting for the Tri-City Herald at the time. I was hired on as their ag and outdoors writer. I lived in a little apartment near the Columbia River.

No one knew me out here. My family name meant squat. No one cared about my family's farm four hours away in Western Washington. And few farmers or ranchers here wanted to talk with the press, let alone talk to me.

I would struggle through days of calls to land even one productive interview. I attended hay conferences, irrigation district board meetings -- anything just to meet more farmers and get some business cards. But slowly, with each good story, I began to gain a reputation. Sometimes that was good, sometimes that was bad. Like the time I wrote that asparagus had 12-feet deep roots. An angry reader and asparagus farmer took me out in his pickup and dug up an asparagus crown to show me the shorter roots himself. Those were some hard lessons. But that pissed-off farmer is still one of my most-trusted sources today. Now, after more than a decade of work, I have a network of growers from near Spokane clear down to near the Oregon border with Nevada.

All this to say: I've built my reputation. Reputation out here is everything. It's what business, social circles and life are centered on.

Stacy Kniveton: I guess I probably more than teaching my kids how to work is to teach that to them: is make, make sure they treat people right and have a good reputation.

Sponsored

Anna King narration: This is Stacy Kniveton, a Columbia Basin farmer. He sits at his kitchen table with my producer Matt Martin and me. His wife Olivia Grassl sits beside him.

Matt Martin: what does a good reputation get you in this community?

Can you, how does it help you?

Stacy Kniveton: Um, it, it, it, it let Marv Grassl let me marry his daughter

Olivia Grassl: You want your reputation to be a positive reputation, meaning that it's, that you can be trustworthy. You're that you're ethical. You're you're honest. you're, you can be a friend.

Sponsored

Stacy Kniveton: It's such a small community here it's a really big deal.

Anna King narration: And Cody Easterday had a hard-working iron-clad reputation in the community. People describe him as a handshake guy. And that good reputation meant a lot as he grew the family business. But it also allowed him to use the family's good name to pull off one of the largest cattle rustling schemes in modern America.

Cody Easterday used his good family name to take advantage of his business partners. He stole more than 244 million dollars by inventing a huge herd of cattle that didn't exist. The swindle was so large that it increased the price of beef for American families. And the whole time the fraud appeared to go unnoticed.

This is Ghost Herd. I'm Anna King.

Alan Schreiber: I don't like using the word empire, but they had a really big, really nice operation going.

Sponsored

Anna King narration: That's Alan Schreiber. He's an Eltopia-area farmer. His place isn't far from Cody Easterday's home in Basin City.

Alan Schreiber: There's no two ways about it. They had a really nice farming operation. It's, it's enviable what they had.

Anna King narration: But what the Easterdays had was built on toothpicks in the sand. It was shifting and listing underfoot.

Cody was stealing money by growing and feeding his ghost herd. But at the same time he was donating money to his community -- keeping up his good reputation.

The large Easterday family was known for being big supporters in the community -- putting their weight behind the Basin City rodeo and the Benton Franklin Fair & Rodeo. The family would even make a special effort to buy up project animals that 4-H kids were selling at the county fair.

And Cody would often donate beef and produce to his community -- he would even do the barbequing himself for summer parties, local school events and funerals.

But the Easterdays didn't do just small-town philanthropy, the family gave to big institutions like Washington State University.

Cody Easterday: we produce a lot of products in our agriculture, uh, production facilities that create biomass

Anna King narration: It's probably worth mentioning that this is about the only time you'll hear Cody talk in this series. That's because he wouldn't grant me an interview. So in this You Tube clip you can hear Cody's slight rural drawl. He's speaking at an event with WSU Tri-Cities. It was after the family had donated 225 thousand dollars to the school to research ways to turn farm waste into fuel.

Cody Easterday: create a fuel that we can use in some part of our operation, whether it's, uh, for boilers and our feed mills, or whether it's for fuel for our trucks or tractors.

Anna King narration: Cody's reputation was so strong and his family was so powerful, I had a very difficult time getting anybody to talk about Cody on the record.

Anna: I wanted to ask you about the Easterdays.

Nicole Berg: Oh, I'm not answering that. I'm not answering nothing. I don't wanna touch it

Ben Casper: I don't want to talk about Cody

Alan Schreiber: I'm not gonna talk about that

Case VanderMeulen: I've known Cody for quite some times. And just leave it at that.

Anna King narration: To say this is a tight-knit community is a gross understatement. It's so tight-knit that it could hold back a tide of Columbia River irrigation water.

And in a tight knit community a good reputation gets there before you do. It was with that stellar reputation, that Cody started doing business with the second-largest meat processing company in the world.

Tyson: More kicks of flavor, more smiling snackers. More to love. Tyson.

Anna King narration: Tyson Foods. Tyson is a multinational corporation that cuts 1 in 5 pounds of all the chicken, beef and pork produced in the U.S. In 2021, they made $47 billion dollars in sales.

And 2 percent of Tyson Fresh Meat's beef came from Cody Easterday's operation. Around this time, Cody was rasing real beef along with his made-up beef.

This is the way the deal works between a giant meat corporation and a rancher: A rancher tells Tyson they're gonna buy some young calves -- animals about 700 pounds. Then Tyson gives them money to buy the animals and to pay for feeding them. Once they're fattened and ready for slaughter -- around 14-hundred pounds -- the rancher delivers the meaty bovines to the Tyson plant. And then it's pay day: The rancher is given the difference between the money they took from Tyson and the current cattle price.

But Cody found a way to exploit this clockwork contracting system. He would tell Tyson he had more cattle than he actually did. From 2016 through about November of 2020, Cody stole nearly a quarter of a billion -- that's a billion with a "b" -- dollars. These animals only existed on paper. But Cody still charged Tyson for the feed and care of the ghost herd.

But what would it have taken to pull off something on this scale? And how did Cody keep it all hidden? We'll get into that right after the break.

BREAK

Anna King narration: I wanted to understand the true scale of the Cody Easterday operation. And how he might have carried out this big fraud. As I mentioned earlier, Cody didn't want to talk to me and he wasn't about to let me on his ranch. So I drove out to another ranch. The Coulee Flatts Dairy outside of Basin City.

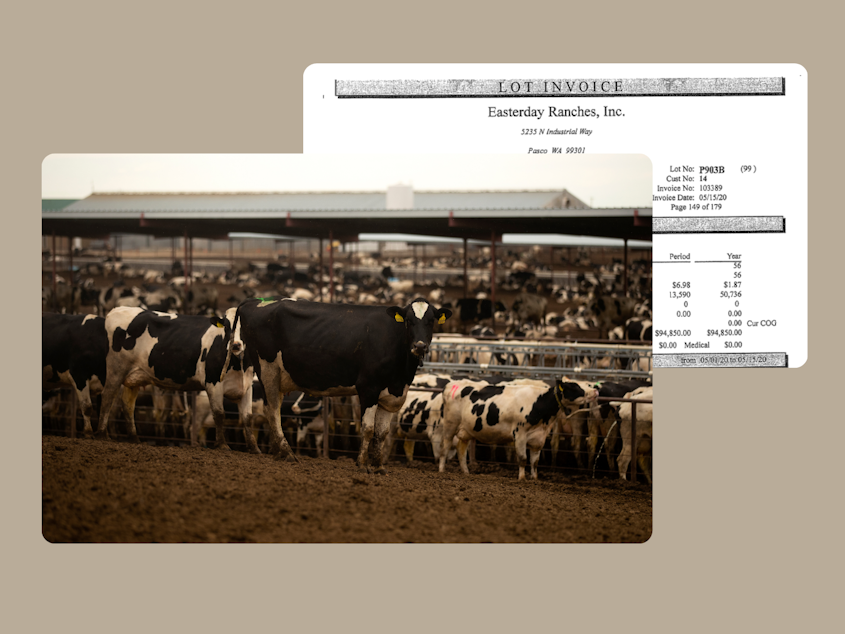

Here you can see how big the Easterday swindle was in plain black and white.

All you see is holstein cows munching in stanchions and pens yawning out into the distance. This dairy has nearly 17-thousand cattle. That number includes the milkin' mamas, the young replacement heifers that are still growing, young steers that are destined for hamburger and even some babies. But even counting the wee ones a couple hours old, it's a lot of freakin' cattle!

To manage this herd takes a ton -- literally. There's 95 people that work here. They work in shifts around the clock everyday of the week. And it takes tons and tons of feed every day. During harvest when the hay and corn are ready, dozens of semi loads of fodder come in daily.

It's difficult to absorb the complexity of it all. I hardly can make out the end of these cattle on the horizon. It's just a mammoth milking operation.

And Cody Easterday's ghost herd was nearly 12-times larger than this massive real-life dairy herd.

A large truck rumbles by as I walk past a grain shed. This is a busy place:

Anna: I'm standing next to the boss. So I don't get run over. Or maybe that's not the best move.

Case VanderMeulen: Probably don't maybe they're upset with me. Who knows

Anna King narration: This is Case VanderMeulen. He owns Coulee Flats Dairy. He's agreed to show me how his crew feeds all his cows. That's unusual. Usually reporters aren't allowed on places like this. His operation is all really precise. Dairy cows are like elite athletes -- they require mass calories in the right balance.

Case VanderMeulen: those are all forages. So triticale, corn silage, haylage, cannery waste,

Anna King narration: All around me are big piles of different kinds of grains. The air is thick with bits of alfalfa, hay and corn dust. My shoulders are coated in a thin layer of brown.

Case VanderMeulen: alfalfa hay, feeder hay, straw, high moisture corn. And then these piles are mixes of the grains that we mix together.

Anna King narration: Just seeing all this here, makes me think thats a big complex mix to fake. Cody would have had to invent all these rations in order to trick Tyson into paying money he didn't earn. I'm hoping Case can help me better understand how Cody pulled this off.

Case is a Dutch immigrant, who started working at a dairy in California, and then started his own dairy with 150 cows in Grandview, Washington. Now his latest dairy sprawls out a little east of Basin City. He's built this. And he's serious about business and numbers.

Case leads me into his office. The air is clean and cool. There's black leather furniture and a large wooden desk. It feels like I just stepped into a big city executive office...except for the huge bronze statue of a milking cow and girl in the corner and his big panting dog.

Case pulls out a calculator to explain the scale of his operation.

Case VanderMeulen: So for corn, for instance, Let me take a look.

We use like 19 tons a day. So if you had 19 tons times seven, so that's 133 tons a week. Divided by 30. So that's between four and five loads a week. So we'll, this week we'll order very most likely five loads for next week.

Anna King narration: Now when feed trucks roll into this operation, it's not like some bumkin just kicks the bales down from the truck and drives off. This is a sophisticated system. It's high tech.

Every new delivery of feed is weighed on a truck scale and compared with the invoices. That way, Case knows he's actually got all he's paid for. The scale reciepts are piped right straight into his office computer, in fact. So he can watch them roll in anytime. He doesn't want to get shorted.

Case VanderMeulen: We gotta weigh everything in and out.

Anna: So what do they call the office and say, I'm sending in my, I'm sending in my number here. I'm on the, on your scale or how ...

Case VanderMeulen: No, there's a computer out there. A touchscreen computer, just like you, like you have, it's a, it's a kiosk. So they type in- Or they come in and they type in whether they're coming in or going out, either delivering or pickup.

And then you can choose from the different commodities or different products, what they're bringing. And then after they unload, then they go back over the scale and they find their ticket and push the button and, and then it'll record and print a ticket.

Anna: Pretty important.

Case VanderMeulen: Very important.

Anna: I mean like how important is that to your operation?

Well, you know, we buy everything by the ton. So, you know, uh, you y'know.. If, if, if you're bringing buying a load and they're bringing in 64,000 pounds, meaning 32 ton, then I wanna make sure that we're being billed for 32 ton.

Anna: You ever had a problem on that?

Case VanderMeulen: Oh, sometimes, but usually not, no big deal, but it's. Just need to make sure it's done correctly.

Anna King narration: Make sure it's done correctly.

Cody Easterday was very good at making things appear like they were done correctly. Cody's operation would have required about all the same tracking that Case does on his dairy, but on a much bigger scale. So how did Cody fake an operation that large?

Darryll Olsen: Cody had really good spreadsheet skills.

Anna King narration: This is Darryll Olsen. He's a Columbia River water expert. And often worked with Cody on different projects. He was always impressed with Cody's attention to detail.

Darryll Olsen: Went into his office one time and I had brought in some spreadsheets and then he pulled out some stuff or we put it up on the screen and it was like, that was very impressive to me, that you would have someone like that that would, you know, had taken the time to learn how to operate those spreadsheets that way.

Anna King narration: It would have been a lot of paperwork to pull off this fraud -- a lot of things to keep track of. A lot of stress. A lot of real work. I asked Case how he thought Cody might have been able to pull off a fraud like this.

Case VanderMeulen: I, I, I, I, I, I understand that the, that there's phantom cows and phantom feed I have, but I have no idea on how, how that transpired or whatever. And like I said, I, don't. Not in that game. I don't know. I have no idea.

Anna King narration: But I know through court documents that Cody created fake feed tickets and sent fraudulent invoices to Tyson. At the same time, Cody was also raising real beef to deliver to the meat giant. To keep the ghost herd's expenses separate in his books, he used the handle -- "Customer 99."

There's a lot of things I'm still trying to figure out about Cody's operation. Like did he do it alone, or have help. But I do know that over the course of four years Cody was able to swindle about a quarter of a billion dollars from Tyson and one other meat company to pay for cattle that never existed.

Alan Schreiber: Now you'd say, well, how come Tyson didn't catch all this?

Anna: How come Tyson didn't catch all this?

Anna King narration: An important question from Alan Schreiber.

Alan Schreiber: You know, I don't know the answer, you know, I don't know. I don't know the answer, but, um, I don't know why Tyson, uh, didn't know that this happened.

I think it's pretty non-controversial to say that at some point, the people in Tyson that were monitoring this, didn't do an adequate job monitoring.

Anna King narration: Tyson might've messed up. It missed this huge fraud -- mystery meat -- over several years.

One potential reason they missed it is because Cody was still delivering real beef to the Tyson plant on schedule. He was meeting the demand so there was little suspicion on Tyson's end.

And when I asked Tyson to talk about it, they declined. But to Tyson's credit, when you're dealing with hundreds of thousands of cattle ... how can you actually count something that big? It is next to impossible to get an accurate count when you have tens of thousands of cattle out on a feedlot.

But mainly, it has to do with reputation. Cody had a good one. And Tyson probably put their trust in that.

Many of the community members I spoke with were just in shock when they found out.

Anna: What did you think when you first heard about Cody's deal? Just in general, just like, as an observer.

Case VanderMeulen: Unbelievable. It's the only word I got.

Anna King narration: So what drove Cody to fraud? Why cheat in such a massive way? Was it just old fashioned greed? Perhaps it had to do with his habit of betting big and losing big?

Eric Belasco: I mean, it, it, it looks, it looks suspicious to me to, to see all those losses year after year.

Anna King narration: Next time we'll dig in to how Cody gambled away his empire, and how all farmin's risky.

This is Ghost Herd. I'm Anna King.

Credits

Anna King narration: Ghost Herd is a joint production of KUOW Puget Sound Public Radio and Northwest Public Broadcasting, both members of the NPR Network, a coalition of public media podcast makers. To support our work, contribute to KUOW, NWPB or your local NPR station … and tell a friend or two about this podcast. It helps.

Ghost Herd is produced by Matt Martin, and me, Anna King. Whitney Henry-Lester is our project manager.

Jim Gates is our editor.

Fact Checking by Lauren Vespoli

Cultural edit by Jiselle Halfmoon

Our logo artwork is designed by Heather Willoughby.

Original music written and performed by James Dean Kindle

Recorded by Addison Schulberg

With additional musicians Roger Conley, Andy Steel and Adam Lange

I'm your host Anna King.

If you have thoughts or questions about Ghost Herd, we’re listening. Get in touch at KUOW.org/feedback.