Remembering The Death Of Seattle's Major Transit Initiative

Before Move Seattle and Bridging the Gap, there was Forward Thrust. Fifty years ago this week civic leader Jim Ellis introduced Forward Thrust at a rotary luncheon at the Olympic Hotel. Forward Thrust was the name for a huge package of infrastructure improvements and for a countywide political campaign Ellis envisioned to get them paid for.

Seattle attorney Gerry Johnson says Ellis brought a new approach to getting things done in King County by building broad support for taxation to pay for specific projects. “It was a creation of a consensus around big ideas, people accepting responsibility, the notion of going to the ballot to ask people to tax themselves,” Johnson said.

Ellis had learned the hard way how to get King County voters to support big ideas. In the 1950s, he had led efforts to create a new regional government for Puget Sound to make cities and counties more efficient. It failed at the ballot box, so Ellis came back with a pared down proposal to create a new government agency to clean up waterways in King County. That measure passed.

But Forward Thrust had a much bigger price tag than sewage treatment. For highways, swimming pools, parks, and what would become the Kingdome, the cost was more than $400 million.

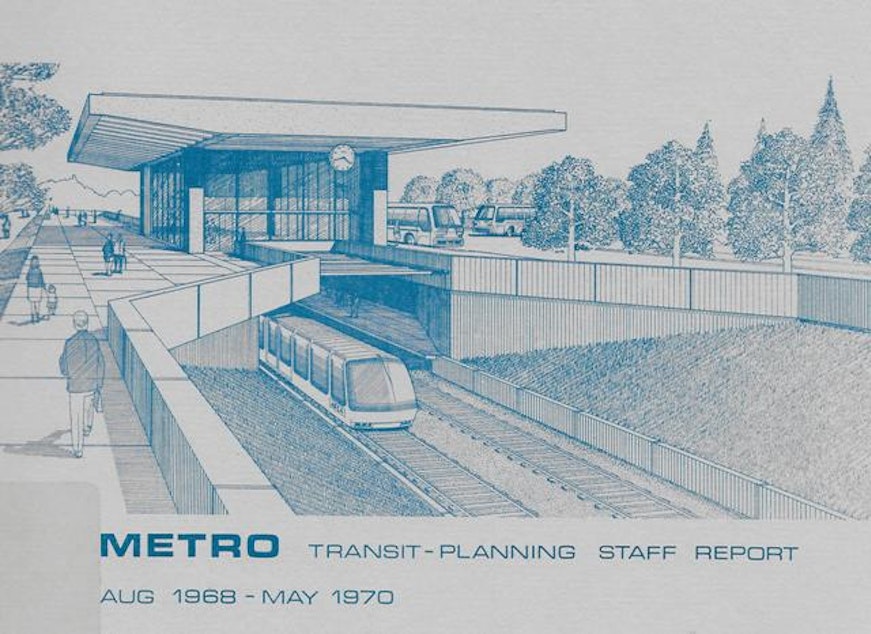

The most expensive element, by far, was a separate measure that would create a commuter rail system connecting downtown Seattle with suburban neighborhoods. For this, voters were asked to approve $385 million in local taxes. If King County voters said “yes,” the federal government had already committed an additional $800 million to build the system. Total cost of the commuter rail system was $1.15 billion, or about $8 billion today.

Sponsored

On February 13, 1968, Forward Thrust appeared on the ballot as 12 separate bond measures. When the votes were counted, seven of the 12 had passed, including those for parks, pools and the Kingdome.

One that didn’t pass was commuter rail.

Phyllis Lamphere, who was a Seattle City Council member in the 1960s and part of the Forward Thrust committee, says this was tragic. Critics, Lamphere says, complained that the system proposed was too focused on downtown Seattle and was much more than the region needed. But Lamphere says that was just shortsightedness. “That's the most significant determinant of our failure to deal at an appropriate time with the transportation needs that we knew were there,” Lamphere said.

Supporters tried again to pass the transit measure in 1970. By then, the economic downturn known as the Boeing Bust was underway, and it failed again. The federal money went to Atlanta instead.

Lamphere says that more recent struggles to tackle issues like transportation and even education are about leadership. She says in order to solve big regional problems, you need someone who can build consensus. Someone like Jim Ellis, says Lamphere, “who can conceive of the structure and can articulate the need and can inspire the population to do something they never thought they could do.”

Sponsored

Jim Ellis is in his 90s now, and doesn’t give interviews anymore. In 2006 he told KUOW what would’ve been different if the commuter rail measure had passed. “If we had done it in 1968, if we had passed it, we'd have been able to do it at a much lower cost,” said Ellis. “Interestingly enough, the system would've been completed in 1985 and the last bonds would've been paid this year [2006].”