The Pacific Northwest was already internationally recognized for glass art. Then came Preston Singletary

Preston Singletary is one of the best-known glass artists to come out of the Pacific Northwest.

For those unfamiliar with the medium, that’s saying a lot.

The Pacific Northwest is, after all, the birthplace of glass art pioneer Dale Chihuly, credited with pushing the centuries-old craft into the realm of fine art. More than 45 years ago, Chihuly cofounded Stanwood’s Pilchuck Glass School, a magnet for artists from around the world. Pilchuck, in turn, sparked the region’s evolution into an international hub for glass artists, galleries and private collectors.

Even among all this creative achievement, Singletary stands out.

For more than three decades, Singletary has not only mastered traditional glass blowing skills, but devised new techniques that allow him to express his singular artistic vision. But that vision didn’t arrive overnight. Singletary’s art developed alongside his embrace of his Tlingit roots – a path that came with risks as Singletary translated traditional visual forms and cultural lore into glass, and was himself shaped by a deeper understanding of his heritage.

Today, an immersive exhibition at Tacoma’s Museum of Glass called “Raven and the Box of Daylight” provides a look at the stunning works forged in this years-long process.

Transformation through glass

Sponsored

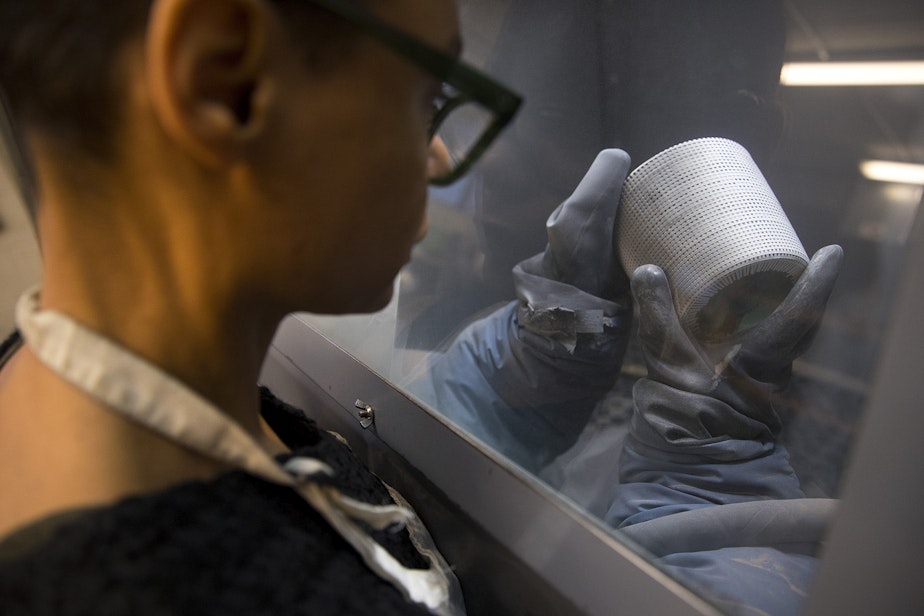

Glass art is a collaborative medium, at least as practiced here in the Northwest. Singletary’s small hot shop—the term for a glass studio—is just large enough to fit two furnaces, a small kiln, a couple of work benches, three sweaty artists and two curious journalists squeezed as far as possible from the flaming torches the artists wield to maintain the temperature of the glass they’re slowly shaping into a raven.

“Sean will gather glass out of the furnace to start to layer the colors,” Singletary explains, referring to one of his assistants, Sean Albert. “Since glass is the consistency of honey, he can only get so much on the pipe at one time. I equate it with making a candle; you dip the wick, wait, then build that layer up.”

Albert collects the molten glass on the end of a long, hollow metal pipe. He fits the pipe into a support stand, blows into one end, then signals to Singletary, who uses two cork pads to give shape to what looks like an opaque blob. The third artist, Janusz Pozniak, occasionally blasts the glass with the flame of one of the torches he’s overseeing.

Sponsored

Watching the three men is like watching a well-rehearsed ballet; they don’t need words to convey when it’s time to heat the glass, or move it back into the furnace. They’ve been working together for many years and it shows.

Slowly, the blob morphs into something more avian; with each minute in the hot furnace, each pass with the cork pads, it comes closer to the form Singletary desires. After almost an hour, the men break the hot glass from the pipe and carry it carefully to another oven where it will slowly cool to room temperature.

For “Raven and the Box of Daylight,” Singletary used similar methods to craft everything from an almost full-sized glass and steel canoe, to a glass river teeming with glass salmon, to a room full of beings in the midst of transformation. All of these intricate artworks are displayed in galleries that are themselves transformed by elaborate audio soundscapes and video installations into coastal Alaska.

Sponsored

The exhibition relays the story of how the trickster Raven made his way into the household of a wealthy man who owned three boxes that Raven coveted. One box held the stars; another held the moon. The third box contained the sunlight. The three boxes were priceless in a world that was still shrouded in darkness.

“Raven is part of a tradition we have, stories about trickster figures,” says Miranda Belarde-Lewis, the exhibition curator who shares Singletary’s Tlingit heritage. “We don’t think of Raven as a god. He’s not the creator, but he is somebody who drastically shaped the world.”

As Tlingit legend has it, Raven was driven to open each of these boxes, releasing their light. Once that happened, the world and its inhabitants were changed forever.

Sponsored

Singletary and his crew spent almost a decade creating the components of the exhibition, but in a sense, it’s taken him almost a lifetime to reach the place where he could realize this vision.

“I grew up very urban,” Singletary says. And, he adds, “I grew up away from the Tlingit culture, technically."

Singletary’s great grandmother enrolled all of her family members in the tribe, and shared some aspects of the culture with them. Singletary was familiar with the Northwest coastal indigenous visual imagery known as formline.

Formline art uses large curves, ovals and sweeping shapes that at first glance may seem abstract but often depict the birds, fish or mammals that populate the coastal environment and are symbols in the Native lore. But in the early 1980s, before he became a name in the art world, Singletary was just another young Seattleite trying to figure out his path in life.

Sponsored

Forging an artistic identity

Singletary was introduced to studio glass during high school, through his good friend and fellow artist Dante Marioni. Marioni’s father, Paul, is a noted Seattle glass artist; the two students hung out in his Wallingford studio after school.

“It felt really special, like New York in Wallingford,” Singletary laughs.

Dante got his friend a job as a night watchman at Seattle’s Glass Eye Studio, a shop that still produces ornaments, paperweights and other glass objects. After Singletary moved to the day shift, the studio artists began to teach him their craft. He enjoyed the work, but like so many teenagers in the 1980s, he dreamed of a career as a rock musician.

For years, Singletary bounced between two art forms. He played in a couple of bands, performing and recording. But he continued to seek out people who could help him develop his glass skills: everyone from regional stars like Marioni to Italian master craftsmen who came to work and teach at Pilchuck.

But mastering a craft isn’t necessarily the same thing as forging a unique artistic identity. For that, Singletary had to acknowledge the cultural heritage he had all but taken for granted. He began to decorate the glass he blew with form line imagery.

“The first pieces I was developing were upside-down hat forms,” he says. “Every glassblower has made that shape at some point or other when developing their skills.”

Singletary refined a sand blasting technique that allowed him to draw ravens, salmon and other imagery onto glass, then blast away the top layers to create multi-colored glass renditions of traditional baskets, masks, even ceremonial screens.

His art was unique, and for more than 20 years sought after by museums and private collectors around the world. But the more Singletary pursued these images, the more curious he became about what they meant to the Tlingit people.

“I often think of a genetic memory that was awakened,” Singletary says. “The more you know, the deeper you reach inside to pull something out.”

The ambassador of glass

In 2004, at the grand opening of the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., Singletary met Walter Porter, a Tlingit storyteller and mythologist he credits with helping to guide him through his cultural explorations.

“He saw this potential for me to reach out through the art world and to share all this information,” Singletary says. “He always said you need to get into the details and really share those ideas with the broader public.”

Now, Singletary calls himself an ambassador of glass. He’s sharing his culture with the art-going public, but he’s also transforming how indigenous people express their history and culture.

Traditionally, Tlingit artists have used abundant natural materials at hand: cedar for carving, bark and grasses for boxes and clothing. But curator Miranda Belarde-Lewis says the customary materials are in decline.

“Either because of logging or there are limits on where to access them,” she explains. “More and more, all indigenous artists will have to start exploring other ways of expressing ourselves as we keep our traditions.”

For Preston Singletary, that means replacing the traditional natural materials with his own medium: glass.

After his initial encounter with Walter Porter, the two men met again at an Alaskan tribal gathering and struck up an ongoing conversation about how Singletary could infuse his glass creations with Tlingit mythology.

“Everybody has a different attitude about how to share the culture with current society. Some things are taboo,” Singletary explains. “With Walter’s encouragement, I was able to have more confidence.”

Walter Porter passed away in 2013, but his influence continued to shape Singletary’s work.

Singletary created an array of glass objects—renditions of traditional rattles and spears, masks and baskets, even large clan screens and totem poles. His reputation among the Southeast Alaskan indigenous people grew as he took more of his work to clan gatherings there.

“Some of the elders would look at it and say, ‘Our art is in really good shape, it’s even in glass,’ kind of as a joke,” Singletary says. “[But] I had to learn a lot of stuff and I had to be bold and try to make strides in my work so it would be accepted.”

Singletary and curator Belarde-Lewis were nervous to see how the elders would respond to “Raven and the Box of Daylight.” “We had some elders at the opening,” Belarde-Lewis says. “They told us that our clan leaders could be proud of us, that we were telling the story in a very conscientious way that wouldn’t offend.”

That’s huge praise, according to Belarde-Lewis.

“This is our patrimony, all the Tlingit people own the story,” she says. “It was our goal to really represent their voices.”

Former Museum of Glass director Susan Warner, who gave the original green light for the exhibition, says Singletary now serves as a role model for younger indigenous artists from around the world.

“It’s really critical to our young artists to see an artist like Preston who’s attained that stature, and has an authentic voice and can be a teacher and a mentor,” Warner says.

Singletary does teach and collaborate with other Native artists, but he remains focused on his own artistic trajectory. In addition to ongoing production for sale in private galleries, he’s taken on large scale public commissions, including a seven-foot-tall lead crystal totem pole based on his great grandmother’s girlhood.

He’s come a long way from the high school kid torn between art and music. But these days, Singletary’s incorporated both. He’s part of a band called Khu.éex', the Tlingit word for ‘potluck.’ Khu.éex', is predominantly Native, fusing their music with indigenous stories and melodies. For Singletary, everything now comes back to family, community and his Tlingit identity.

“People say, ‘Oh, you’re Tlingit and you have this rich culture you can draw on,” says Singletary. “Well, everybody has a story, everybody comes from somewhere. You have to know your story. Unlocking the freedom in your own life so that you can do the things you’re meant to do.”

“Raven and the Box of Daylight” is on view at Tacoma’s Museum of Glass through September 2nd 2019.