The secret world of nukes in Washington state

Beneath the still waters of Puget Sound, submarines loaded with nukes patrol the Kitsap Peninsula and beyond.

Farther east, at Joint Base Lewis-McChord on Interstate 5 near Tacoma, is the only U.S. military unit to call for transportation of nuclear weapons by air.

Even farther east, in Richland, is the Hanford Site, historically the nation's biggest producer of plutonium for nuclear weapons.

Washington state has been home to nuclear weapons-related projects for decades — some well-known, others shrouded in secrecy. These projects have contributed to a robust nuclear presence in the military, a booming nuke industry — and death and injury to hundreds of thousands of people in Washington state and across the Pacific.

Washington “has been at all levels a cornerstone of the U.S. nuclear enterprise,” said Hans Kristensen, director of the Federation of American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Project.

P

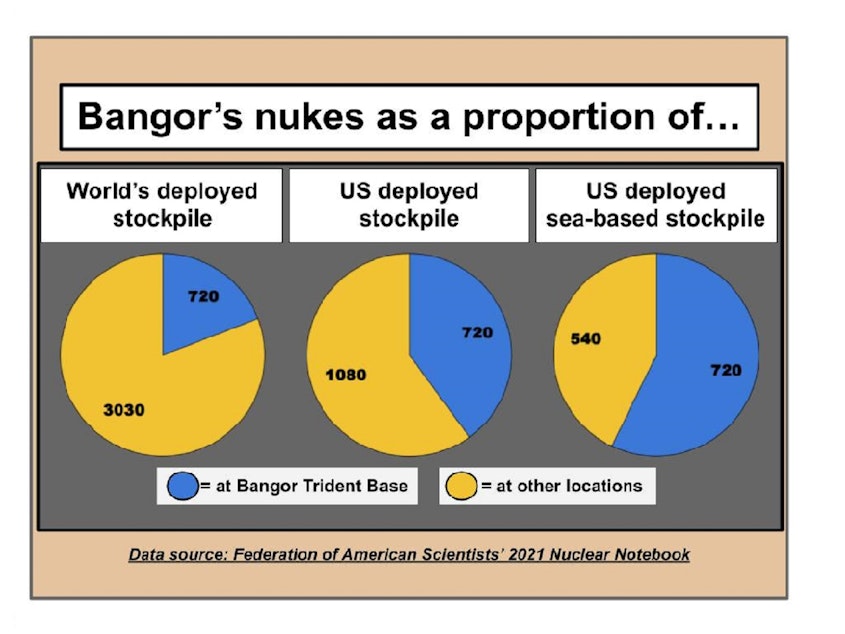

uget Sound is home to around one-third of the nation’s active nukes.

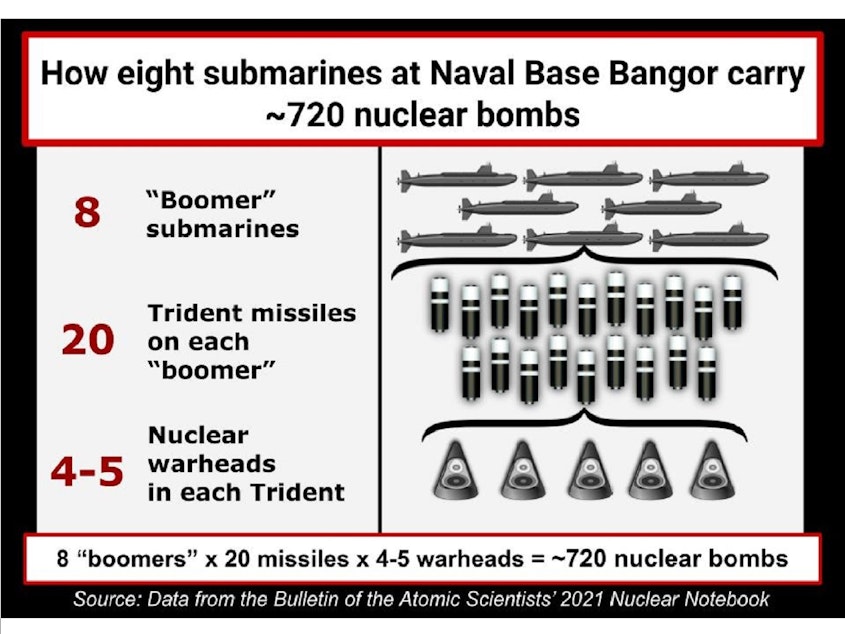

Bangor Submarine Base on the Kitsap Peninsula, near Poulsbo, has around 720 nuclear warheads, according to a Federation of American Scientists’ report. These nukes are loaded into Trident missiles, then aboard eight submarines that roam the waters.

Each warhead could destroy a city, kill millions, and jeopardize the environment and future generations through “long-term catastrophic effects,” according to a United Nations web page.

Sponsored

J. Overton, public affairs officer for Navy Region Northwest, said these submarines provide “constant strategic deterrence.”

Deterrence is the theory that the threat of nuclear weapons prevents violence and war — including nuclear war. The logic: If a nuclear nation attacks another, or its allies, counterattack is certain — so why risk it?

Next door to the Bangor base is a nonprofit that advocates for the abolition of nukes, Ground Zero Center for Nonviolent Action. Leonard Eiger, a member of the group, said that deterrence theory is a sham, and any use of nukes would likely provoke all-out nuclear war, “causing an unimaginable number of immediate deaths and apocalyptic radioactive fallout.”

“It’s only a question of time before either accidentally or intentionally, the weapons are used,” Eiger said. “What security is there in that?”

Sponsored

J. Overton responded that the Navy takes security around these nukes “very seriously,” but declined to comment on specifics.

For transporting nuclear weapons and materials by air, there’s only one United States military unit to call — the 62nd Airlift Wing at Joint Base Lewis-McChord in western Washington. Sgt. Rachel Williams, public affairs officer, calls this a “special trust and responsibility mission” that emphasizes safety.

In Spokane County, Fairchild Air Force Base fuels nuclear-armed planes while they’re in flight, and can do so “even in a nuclear environment,” said Cpt. Kaitlin Holmes, Fairchild spokesperson.

Sponsored

Military bases with nuclear responsibilities would make Washington state a likely target in an atomic war, said Kristensen, of the American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Project.

“Once you have nuclear weapons, and you operate nuclear materials, you open up the potential for a wide range of hazards,” Kristensen said. He said that trying to mitigate hazards is “sort of a never-ending battle.”

Seth Weinberger, an international relations professor at the University of Puget Sound, disagreed. “It might not be pleasant to think that we’re going to be the targets,” he said. “But that’s what creates the stability.”

Sponsored

Fairchild Air Force Base played a role in the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.

After discovering that the Soviet Union was putting nuclear weapons in Cuba, President John Kennedy wanted them gone. But the Soviets refused — they already had American nukes in their own backyard, and wanted to help Cuba deter further U.S. aggression.

The U.S. and Soviets faced off for 13 days, with the threat of nuclear war looming large.

If an atomic weapon — rather than agreement — had cut the tension, it might have flown from Fairchild.

That was the only squadron with missiles “online and operationally capable of hitting Cuba” at the start of the crisis, said Fairchild’s historian, Rebekah Horton.

Sponsored

T

here have been nuke-related mishaps in Washington, but no official count. The government often won’t say whether an incident involved nukes.

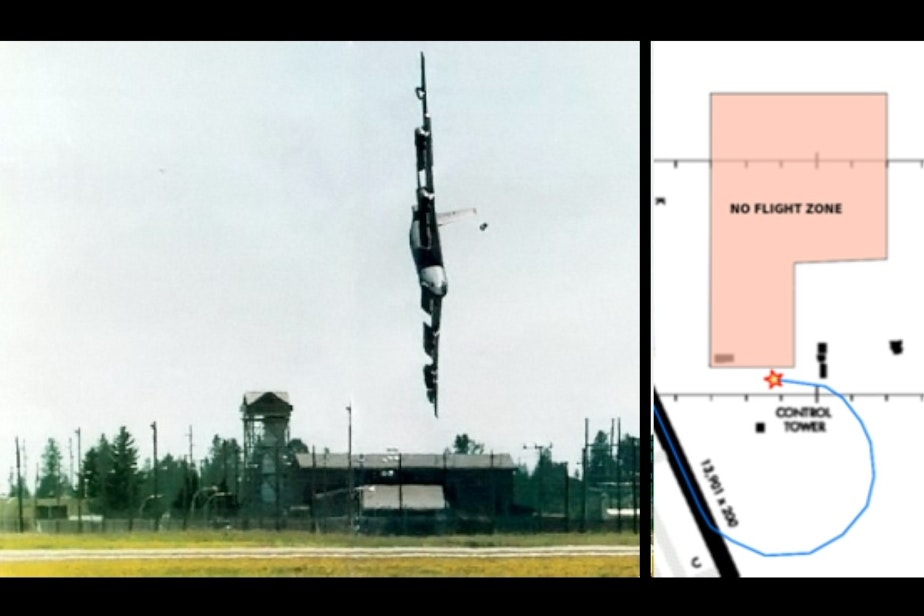

In 1994, a Boeing B-52 practicing for an air show at Fairchild Air Force Base crashed, killing four people. The impact missed a nuclear weapons storage bunker by 50 feet, according to witness statements at the time.

Initially, Horton, Fairchild’s historian, told KUOW that all nuclear weapons were “definitively” removed from the base in 1991, suggesting the bunker didn’t have nukes at the time.

But government reports state that 85 nuclear bombs remained at Fairchild at least through 1997. When KUOW presented those reports to Horton, a spokesman responded that they couldn’t confirm or deny the presence of nukes at any time.

Records obtained by Glen Milner of Ground Zero revealed four incidents between 2009 and 2017 in which Bangor's nuke-carrying submarines collided with objects, including logs and vessels, and one “near miss with a merchant ship.” None of the incidents was catastrophic.

Secrecy is “where the problem lies,” Milner said. “When you try to keep things too secret, the people who should know about it don't.”

“The Navy will tell you we haven’t had an accident with a Trident missile in 40 years, which is in my mind a very poor argument,” Milner said. “Why isn’t it going to happen next year?”

W

ashington state is a key player in the nuke industry — business is booming, as the U.S. modernizes its arsenal.

Of the top 11 companies receiving nuke-related government contracts in 2020 — according to an International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons report — nine perform work in Washington.

Among those top contractors in 2020 was Boeing, the aerospace giant founded in Seattle. Boeing was Washington’s largest recipient of federal contracts over the last year, receiving nearly $6 billion — more than four times the amount of the next-largest recipient.

“Boomer” submarines, like those at Bangor, will be replaced between 2027 and 2040 — at an estimated cost of over $109 billion, according to a Congressional Research Service report released in October.

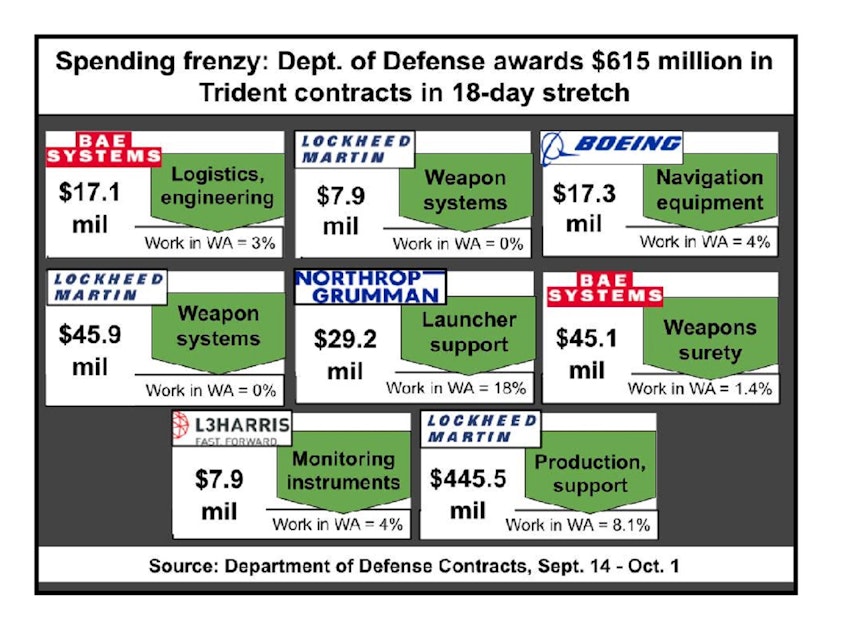

Trident missile upgrades are also underway. Over 18 days ending in October, five corporations received contracts worth more than $615 million for work on Trident weaponry. Some work will occur in Washington.

I

n the 1980s, the U.S. Department of Energy raised concerns about a threat to the nation’s nuclear stockpile: a looming tritium shortage.

Tritium is a key ingredient in each U.S. nuke, used to boost explosive power. Continuous supply of tritium is needed to build more nukes, and to maintain the current stockpile. Because tritium decays relatively quickly, it must be regularly replenished.

“It’s a very important component of both the modernization and the future maintenance of the arsenal,” Kristensen said.

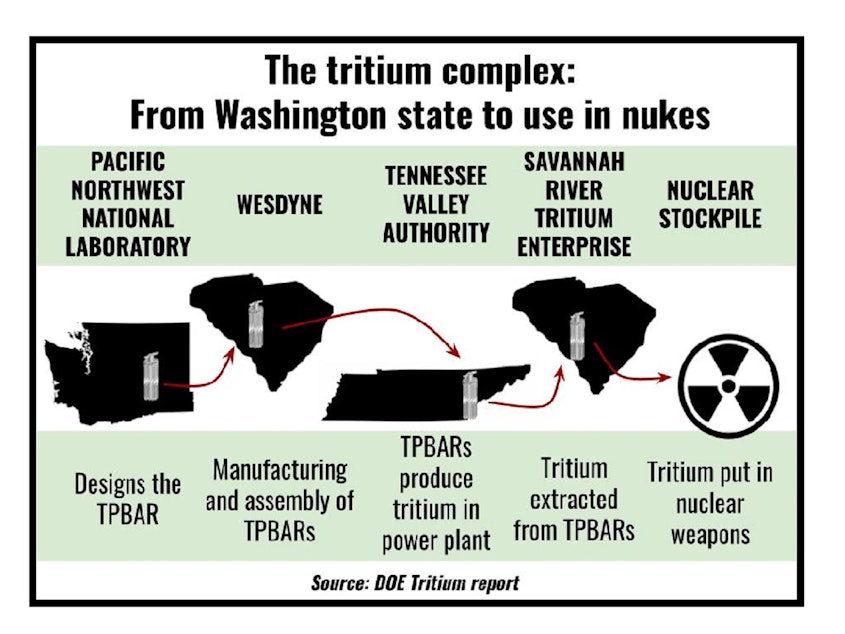

For over 17 years, the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in Washington has helped solve the tritium shortage by inventing a tool that produces and captures tritium — it’s the tritium-producing burnable absorber rod.

The laboratory has continued to tweak the rod design for maximum tritium production.

The lab’s spokesman first commented that it “has not been involved in nuclear weapons (research & development).”

When pressed on specifics, the laboratory’s senior public affairs advisor, Greg Koller, clarified that it “has done work to support the nation’s nuclear deterrent.”

Battelle Memorial Institute, which operates the laboratory, was Washington’s second-largest recipient of federal contracts over the last year, $1.3 billion.

I

n 1996, the U.S. signed the United Nations Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, banning live nuclear weapons tests.

The Department of Energy instead turned to computer simulations and laboratory experiments to evaluate its stockpile, and established the Institute for Shock Physics at Washington State University to support these efforts.

This “is very basic science associated with what happens to matter when it’s compressed under very high pressures,” said Christopher Keane, the university’s vice president for research.

This research, funded by the National Nuclear Security Administration, has contributed to certification of “the nuclear stockpile components over 25 years without nuclear testing,” Keane said. “It’s a tremendous technical achievement.”

T

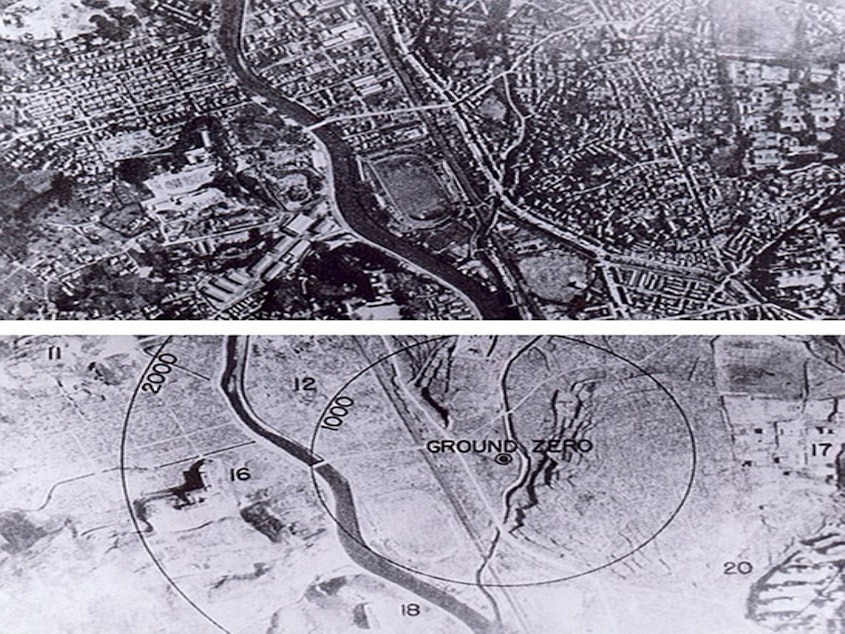

he U.S. attacked Hiroshima, Japan, in 1945 with the first nuke ever used in war, killing more than 100,000 people.

About two years before that, the Manhattan Project arrived at Hanford in eastern Washington. General Leslie Groves — head of the secret project, and a Seattle Queen Anne High School alumnus — approved the site.

Around 50,000 people worked there, but most didn’t know what they were working on until hours after the Hiroshima attack.

“To nearly everyone, the news of what Richland was helping to make came as a complete surprise,” reported The Villager, a local newspaper. “Jubilation and satisfaction follows revelation of product manufactured here.”

That product: plutonium. Three days later it fueled the U.S.’s second and last atomic attack on Japan.

Thirteen-year-old Terumi Tanaka was at home in Nagasaki that day. He survived, but tens of thousands of people, including five members of his family, died from the attack and its fallout. “Around us people were dying everyday,” said Tanaka. “I saw the complete unbearably miserable destruction.”

Hanford workers and residents in the nearby Tri-Cities were proud of their contribution to the bomb — they believed it ended World War II and saved lives.

Today, atomic symbols can be found throughout the Tri-Cities.

There is debate over whether the bomb ended World War II, or only assured Japanese surrender to the U.S. rather than to the Soviets. Its morality, and whether it cost or saved more lives, is also debated.

Tanaka said he doesn’t fault those who made the plutonium, but hopes people working on nuclear weapons today reflect on what they’re creating. “People who think it is okay to use that kind of weapon during war, I want them to rethink their position,” he said.

Hanford produced most of the nation’s plutonium for nukes, from 1943 to 1987.

Washington also produced uranium for nuclear weapons, including at the Midnite Mine — located on the Spokane Tribe of Indians’ reservation — from 1955 to 1981.

Many tribal members worked there, and later suffered high cancer rates, a 2011 study by the Department of Health and the Northwest Indian Health Board found.

C

leanup at Hanford — the nation’s most contaminated area, according to a US Atomic Energy Commission document — began in 1989, and has cost billions.

Recent Department of Energy estimates expect that it will take decades and an additional $677 billion to finish the cleanup. Four of the state’s top five recipients of federal contracts over the past year participate in cleanup efforts.

The cleanup also costs some workers their health.

Abe Garza was once a lover of mathematics, avid reader and runner, but his life is very different now. He copes with neurological and lung damage, loss of smell, difficulty balancing, and partial vision loss.

“It happened so gradually that I didn’t realize what was happening to me,” Garza said. Garza said these illnesses stemmed from his 33-year career at Hanford, where he was exposed to high levels of mercury and other toxins.

A majority of 1,600 former or current Hanford workers, surveyed for a Department of Commerce report released in June, said they were exposed to toxins. Over one-quarter said they’ve been sick as a result.

Workers wrote in the survey that local healthcare is biased toward Hanford management. “Doctors refuse to say the problem could have been a result of working at Hanford,” said one respondent.

Multiple workers also wrote that they don’t trust Hanford’s record-keeping. The Department of Energy “has hidden the truth in medical records,” said one respondent.

Government reports over the years have found that Hanford concealed information on dangers, underreported toxic leaks, collected bad data, violated safety codes, and fostered an environment of retaliation.

Not all studies say this, however. This year, a University of Washington study found that data doesn’t support “a pervasive pattern of occupational disease” for workers at one of Hanford’s most toxic areas. Most authors “received partial support” from a Hanford contractor while conducting the research.

Hanford management, including the Department of Energy, declined to comment.

At the Midnite Mine are 20 contaminants posing “unacceptable risk” to humans and the environment, according to an Environmental Protection Agency web page, which said these risks are currently being controlled.

But some members of the Spokane Tribe say high rates of cancer and other illnesses stem from the mine. Various studies on uranium mines link them to various illnesses.

Safety concerns alter the Spokane Tribe’s lifestyle. Before the atomic age, tribal members caught rainbow trout from nearby Blue Creek.

But now, most “just avoid the area… they just don’t fish it,” said Brian Crossley, manager of the tribe’s Water and Fish Program. Crossley said there is some uncertainty about how much toxicity stems from the mining, versus from the natural environment.

Newmont Mining, the parent of the company which operated Midnite Mine, declined to comment.

T

he U.S. detonated 67 nukes at the Marshall Islands, from 1946 to 1958. Many contained plutonium from Washington state.

Washington also supplied troops for this nuclear testing — including some from Spokane County’s Fairchild base.

For the Marshallese, these tests were attacks. They were burned, sickened, dislocated from their homes, and left with poisoned air, land, food and water.

Dr. Robin Narruhn, a nursing professional and Seattle University professor, said the fallout still afflicts Marshallese people with trauma, high cancer rates, early mortality, and birth anomalies.

After radioactivity poisoned much of their traditional diet, the Marshallese also have high diabetes rates.

Even today, the Marshall Islands is among the world’s most radioactive places. Fallout, climate change and poverty continue to force Marshallese away from home.

“Most Marshallese don’t want to come to the U.S., they would far rather stay,” said Narruhn, who is Marshallese on her father’s side. “We’re sort of forced refugees.”

Around one-third of the Marshallese population now resides in the US. The U.S. government promised them healthcare in a 1986 treaty, then revoked that 1996, and only restored it last year. Washington state restored that healthcare in 2018.

Narruhn said the fight for healthcare continues, as structural barriers persist.

“Not only because we deserve it,” Narruhn said. “But because it was actually the United States’ nuclear explosions that were brought upon us and our islands that are making us so sick.”

Washington’s hand in human testing

The U.S. also experimented on Marshallese people without consent.

This was called Project 4.1. Researchers from the University of Washington and Hanford were involved.

Project 4.1 documents state two purposes — first, to study how radiation impacts the human body. Second, to provide medical care for those harmed.

The U.S. said Marshallese exposure to radioactive fallout – debris from the sky after testing – was accidental. But others say human testing was planned from the start. A document written months before the fallout occurred referenced Project 4.1.

No documents on Project 4.1 were public until 1993, and many remain secret. Radioactive human testing happened in Washington, too.

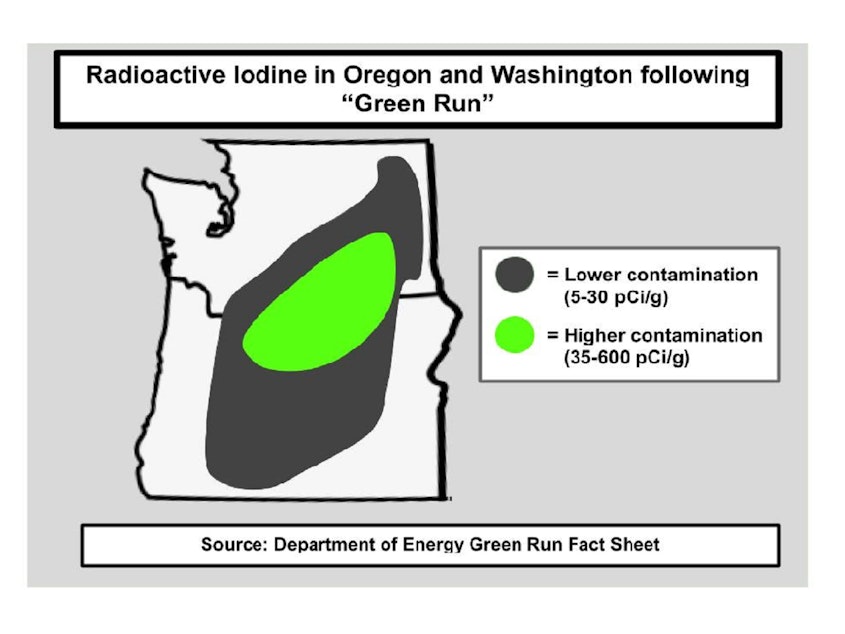

On a December night in 1949, the Air Force deliberately released radioactive gases into the atmosphere around Hanford, which spread through Oregon and Washington.

This is known as Green Run. A declassified document on the experiment mentioned “previous tests,” but no details on those.

In the 1960s, 64 people incarcerated at Walla Walla’s state penitentiary were subject to radiation of their testicles. This research, sponsored by the University of Washington, was cancelled over a decade later after ethical concerns were raised.

The remains of some victims of radioactive testing were obtained by Washington State University’s National Human Radiobiology Tissue Repository, where research continued even after death.

Natalie Newcomb contributed to the reporting for this story.