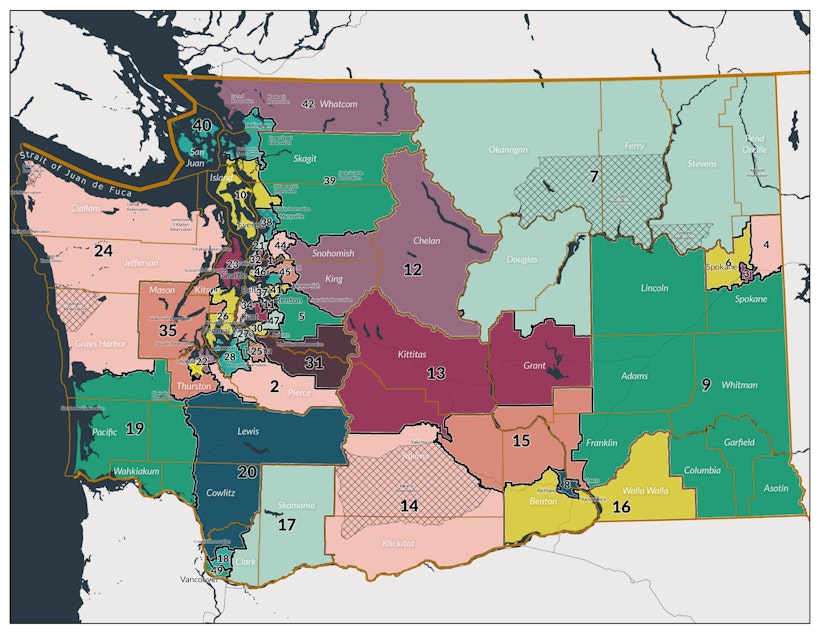

Voting Rights in the Yakima Valley — Redrawing the 15th Legislative District

A federal judge invalidated Washington’s 15th Legislative District map in early August 2023.

That map had been put together by the Washington State Redistricting Commission in November of 2021, and, pretty much, nobody liked it.

Shortly after the commission adjourned, a coalition representing Latino voters sued, saying the map violated the federal Voting Rights Act, because it diluted the electoral power of Latino voters.

Mark Gaber is the Senior Director of Redistricting at the nonprofit Campaign Legal Center, which helped bring the case in Yakima Valley to trial.

"The way that district lines are drawn, you can draw a straight line from what the maps look like to what policies get enacted," he explained. "They determine whether or not representational government is fair and in line with the views of the voters.”

“How the map is drawn determines whether or not you'll get an elected representative, who is actually attuned to your local needs, or one who maybe is paying more attention to some other region that has more voters in the district. And so it's really important to making sure that there's a sort of good, honest government.”

Drawing boundaries for the 15th District was one of the commission’s most difficult agreements to reach before it adjourned. Commissioners wound up creating a district where Latinos comprised 73% of the total population, but only an estimated 51.5% of voting-age residents.

Sponsored

“By doing that, the district was drawn in a way that it was just barely majority Latino," Gaber explained. "But because of turnout differentials, the election result data show that it would just almost never perform to elect the preferred candidates of Latino voters.”

Gaber and other members of the coalition argued that since Latino voters in the area don’t have a history of high turnout, drawing the map this way essentially hamstrung their voting power.

U.S. District Court Judge Robert Lasnik agreed.

“The question in this case is whether the state has engaged in line-drawing which, in combination with the social and historical conditions in the Yakima Valley region, impairs the ability of Latino voters in that area to elect their candidate of choice on an equal basis with other voters. The answer is yes,” Lasnik wrote in his 32-page decision.

Now it’s up to the state Legislature to get the process of drawing a new 15th District map started, but it’s far from an easy road. First, Governor Jay Inslee has to call a special session, and a supermajority of lawmakers have to approve calling the state’s redistricting commission back.

Sponsored

Judge Lasnik said the new maps must be finalized by late March, so they can be in place for the 2024 elections, and if the Legislature doesn't act, the court is expected to take over the process starting in mid to late January.

The Yakima Valley case is on the vanguard of a new wave of challenges to voting district lines across the country, many sparked by a major Supreme Court ruling earlier this year. At stake is power to control state legislatures and even the U.S. Congress.

Christian Grose is a Professor of Political Science and Public Policy at USC. He tracks these cases and their implications.

"I think this case is a really straightforward application of Section Two of the Voting Rights Act," Professor Grose told Libby Denkmann.

"This is one of those voting rights cases that require a lot of analysis of data. And once you look at the data, Latino voters' votes were being diluted and the districts have to be redrawn."

Sponsored

Professor Grose broke down the two ways that the law dictates that race can be considered when drawing district maps, and how these two views don't actually contradict each other.

First, mapmakers cannot engage in Racial Gerrymandering. Meaning, they cannot draw districts specifically to maximize the number of a specific demographic of voter.

"If you try to maximize voters of color in a district, and the district looks really weird, or there's a lot of strange shapes or juts in and out grabs in little neighborhoods, for racial purposes, that would be unconstitutional due to racial gerrymandering," Professor Grose explained.

Second, mapmakers are bound to Section Two of the Voting Rights Act, which means they have to look at the data to see if race relevant enough to the point that voters of color have votes been diluted.

"In this case, unlike racial gerrymandering, you have to actually spend a lot of time thinking about preconditions, looking at data, assessing if there's been a history of discrimination against voters of color," Professor Grose said. "And specifically, what that usually involves is, 'Is there racially polarized voting?'"

Sponsored

You can listen to the entire conversation in the audio above.